This post was originally published on here

A ribbon worm kept in a laboratory aquarium for decades has turned out to be the oldest known example of its kind. Its age, once overlooked, is now reshaping what scientists know about the lifespan of these animals.

The worm is a nemertean, a group of soft-bodied marine predators found from tide pools to the deep sea. Its species is Baseodiscus punnetti, and it has been alive for at least 26 years, possibly closer to 30. Until now, the longest-lived ribbon worm on record had survived just three.

The finding, reported in the Journal of Experimental Zoology, emerged from a long relationship between an animal and a scientist who never thought to ask how old the worm really was.

One really old worm

In 2005, Jon Allen was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, when he learned that renovations would displace a tank of marine invertebrates. He adopted them in order to save them. One of them was a ribbon worm, already an adult, collected sometime in the late 1990s from the San Juan Islands.

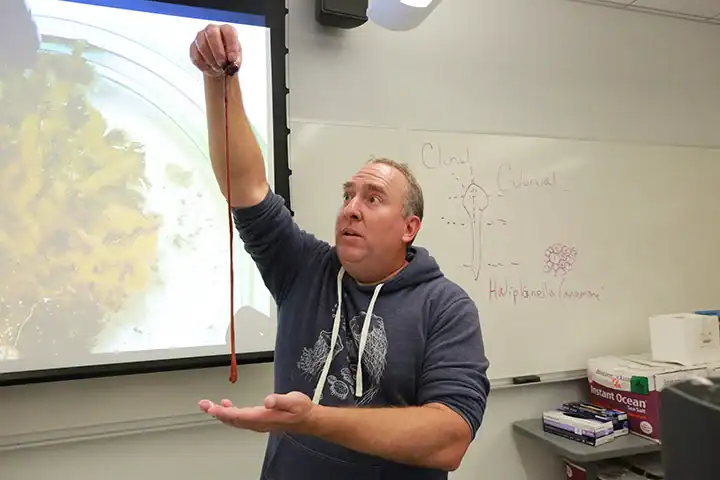

That worm followed Allen across the eastern United States—first to Maine, then to Virginia, where Allen is now a biologist at William & Mary. Year after year, it lived in its tank, burrowing through mud and feeding on peanut worms. Allen brought it out once a year for his fall classes, lifting the meter-long animal from the water with care. It never occurred to him to investigate the worm until a former student asked how old it was.

That student, Chloe Goodsell ’24, suggested genetic testing. A tiny piece of tissue was sent to Svetlana Maslakova, a specialist in ribbon worm genetics at the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology. The analysis confirmed the species as Baseodiscus punnetti, making the animal—now affectionately known as Baseodiscus the Eldest, or B—the second member of its species ever genetically barcoded.

More striking was the timeline. Because B had been collected as an adult in the 1990s and continuously kept in aquaria since 2005, researchers could confidently say it was at least 26 years old.

“Ribbon worms are an incredibly diverse and widespread phylum, yet almost nothing is known about their natural longevity,” Allen said. “This finding fills a genuine knowledge gap, increasing their known lifespan by an order of magnitude.”

Not what you’d expect

Ribbon worms already hold a record of sorts. In 1864, one found on a Scottish beach reportedly stretched to around 55 meters (180 feet), making it the longest animal ever documented. Length, however, is more obvious than age. Soft-bodied animals rarely leave growth rings or other biological signs of aging.

In laboratories, ribbon worms typically survived only a few years. Many biologists suspected the animals might live far longer in the wild, but there was no evidence to prove it.

B changes that. The study suggests that at least some nemerteans are longer-lived than expected. That matters because ribbon worms are predators, often near the top of food webs on the seafloor.

“Our hope is that the work we have done here will show people that members of this phylum of worms are not short-lived, ephemeral members of the marine realm,” Allen told Gizmodo. “Instead, they are decades-long inhabitants and often high-level predators in benthic ecosystems.”

Marine biology already offers examples of extreme longevity. Some deep-sea tube worms can live for centuries. Certain clams have been dated to more than 500 years. Ribbon worms, however, add a new twist. They are active hunters, not sedentary filter feeders. They are also widespread, common, and ecologically important. Even so, much about their lives remains unknown.

A Rare Reference Point

Because scientists cannot yet determine the age of ribbon worms from their bodies alone, B serves as a rare reference point. With a roughly known age, researchers can begin looking for traits that change over time at the cellular level, in tissues, or in behavior.

“Understanding how animals evolve long life spans has implications for human health research,” Goodsell said. “Our finding contributes to the growing body of knowledge of what it takes to avoid senescence—or ‘getting old.’”

Such connections should be made carefully. Worms are not people. But across biology, long-lived animals have revealed unexpected strategies for maintaining cells and repairing damage. Each new example broadens the comparative picture.

B remains in his tank at William & Mary, still alive and kicking (or sliding). Allen does not yet know what the future holds for the worm as a research subject. For now, the goal is simple.

“My hope is that he will continue to live a long life in his tank,” Allen concluded.