This post was originally published on here

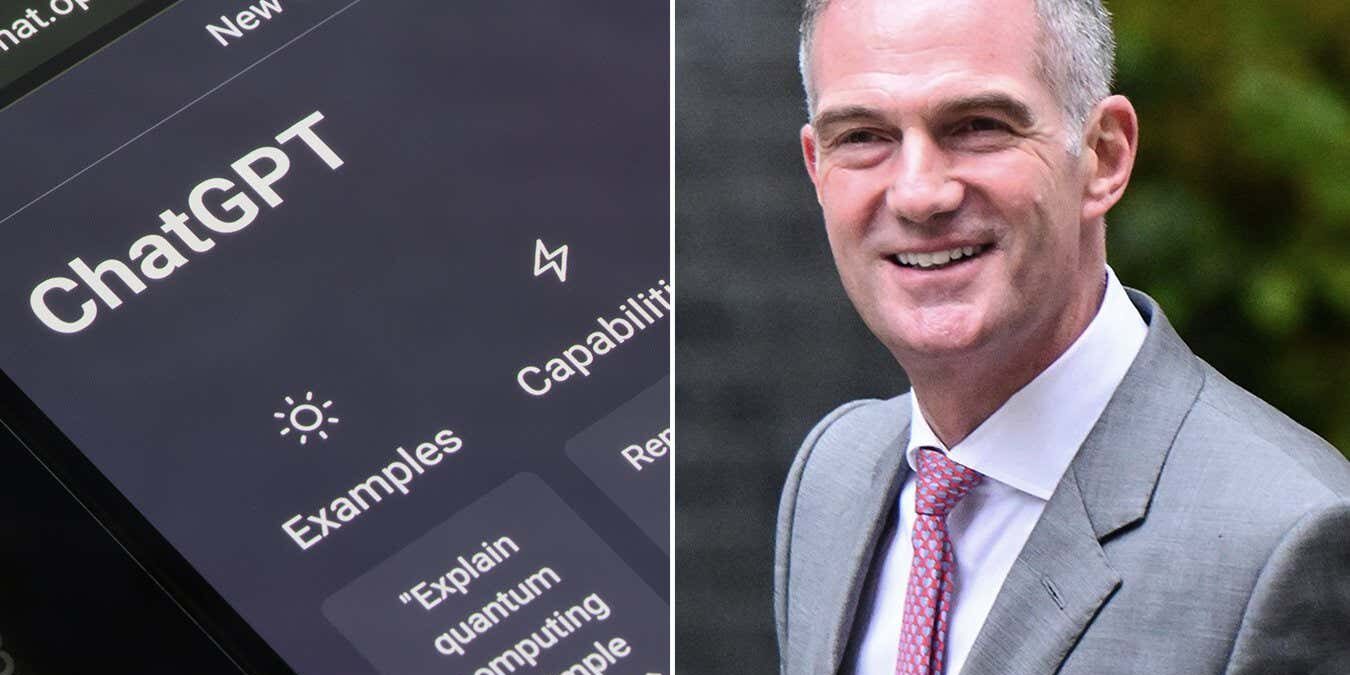

Our successful request for Peter Kyle’s ChatGPT logs stunned observers

Tada Images/Victoria Jones/Shutterstock

When I fired off an email at the start of 2025, I hadn’t intended to set a legal precedent for how the UK government handles its interactions with AI chatbots, but that is exactly what happened.

It all began in January when I read an interview with the then-UK tech secretary Peter Kyle in Politics Home. Trying to suggest he used first-hand the technology his department was set up to regulate, Kyle said that he would often have conversations with ChatGPT.

That got me wondering: could I obtain his chat history? Freedom of information (FOI) laws are often deployed to obtain emails and other documents produced by public bodies, but past precedent has suggested that some private data – such as search queries – aren’t eligible for release in this way. I was interested to see which way the chatbot conversations would be categorised.

It turned out to be the former: while many of Kyle’s interactions with ChatGPT were considered to be private, and so ineligible to be released under FOI laws, the times when he interacted with the AI chatbot in an official capacity were.

So it was that in March, the Department for Science, Industry and Technology (DSIT) provided a handful of conversations that Kyle had had with the chatbot – which became the basis for our exclusive story revealing his conversations.

The release of the chat interactions was a shock to data protection and FOI experts. “I’m surprised that you got them,” said Tim Turner, a data protection expert based in Manchester, UK, at the time. Others were less diplomatic in their language: they were stunned.

When publishing the story, we explained how the release was a world first – and getting access to AI chatbot conversations went on to gain international interest.

Researchers in different countries, including Canada and Australia, got in touch with me to ask for tips on how to craft their own requests to government ministers to try to obtain the same information. For example, a subsequent FOI request in April found that Feryal Clark, then the UK minister for artificial intelligence, hadn’t used ChatGPT at all in her official capacity, despite professing its benefits. But many requests proved unsuccessful, as governments began to rely more on legal exceptions to the free release of information.

I have personally found that the UK government has become much cagier around the idea of FOI, especially concerning AI use, since my story for New Scientist. A subsequent request I made via FOI legislation for the response within DSIT to the story – including any emails or Microsoft Teams messages mentioning the story, plus how DSIT arrived at its official response to the article – was rejected.

The reason why? It was deemed vexatious, and sorting out valid information that ought to be included from the rest would take too long. I was tempted to ask the government to use ChatGPT to summarise everything relevant, given how much the then-tech secretary had waxed lyrical about its prowess, but decided against it.

Overall, the release mattered because governments are adopting AI at pace. The UK government has already admitted that the civil service is using ChatGPT-like tools in day-to-day processes, claiming to save up to two weeks’ a year through improved efficiency. Yet AI doesn’t impartially summarise information, nor is it perfect: hallucinations exist. That’s why it is important to have transparency over how it is used – for good or ill.

Topics: