This post was originally published on here

Fossils can reveal far more than the shapes of ancient creatures. Molecules preserved inside old animal bones provide clues about past diseases, what those animals ate, and the climates they lived in.

For the first time, researchers have examined metabolism-related molecules preserved in fossilized animal bones dating back between 1.3 and 3 million years. This analysis offers a new way to understand not only the animals themselves but also the environments in which they lived.

Chemical signals linked to metabolism revealed details about the animals’ health and diets, allowing scientists to reconstruct aspects of their surroundings, such as temperature, soil conditions, rainfall, and plant life. The results, published in Nature, indicate that these ancient landscapes were generally warmer and wetter than they are today.

Metabolites, the molecules produced and used during digestion and other chemical processes in the body, can provide valuable clues about health, disease, and influences from diet or environmental exposure. Although metabolomic techniques are now widely used to study modern human illnesses and medications, they have rarely been applied to ancient organisms. Fossil research has instead focused mainly on DNA, which is most often used to determine evolutionary relationships rather than environmental or physiological conditions.

“I’ve always had an interest in metabolism, including the metabolic rate of bone, and wanted to know if it would be possible to apply metabolomics to fossils to study early life. It turns out that bone, including fossilized bone, is filled with metabolites,” said Timothy Bromage, professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry and affiliated professor in NYU’s Department of Anthropology, who led this study with an international team of researchers.

Measuring metabolites

Recent discoveries have shown that collagen, the protein responsible for providing strength and structure to bones, skin, and connective tissues, can survive in ancient skeletal remains, even in dinosaur fossils.

“I thought, if collagen is preserved in a fossil bone, then maybe other biomolecules are protected in the bone microenvironment as well,” said Bromage, who directs the Hard Tissue Research Unit at NYU College of Dentistry.

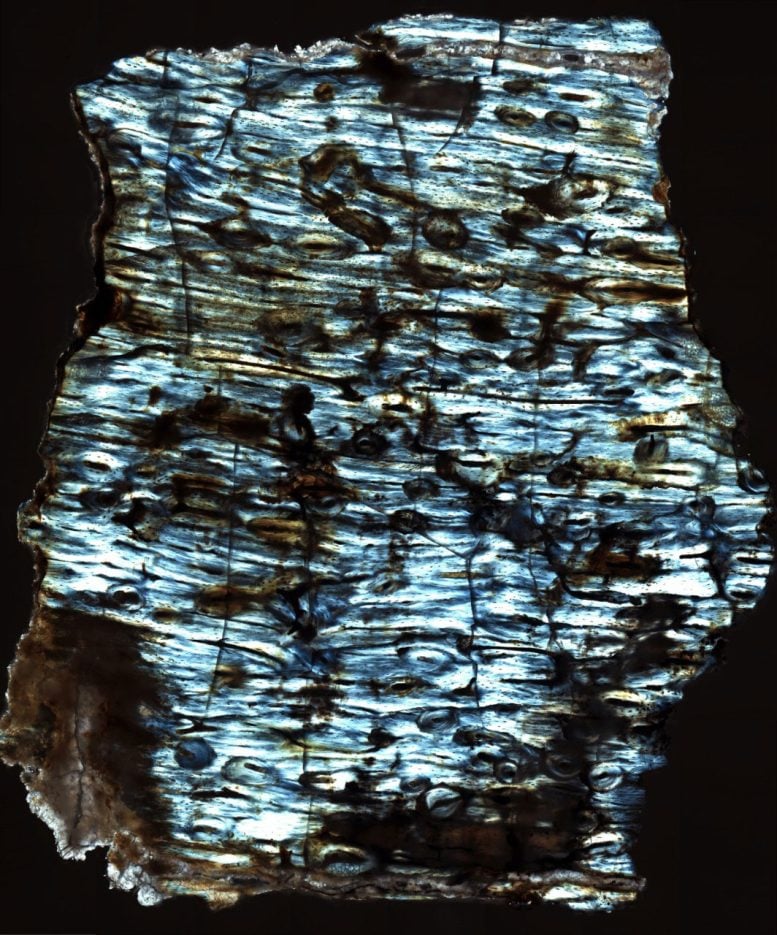

Bone surfaces are porous and permeated by networks of tiny blood vessels that transfer oxygen and nutrients between the bloodstream and skeletal tissue. Bromage proposed that as bones form, metabolites circulating in the blood may seep into small pockets within the bone and remain preserved there over long periods of time.

To test this idea, the researchers employed mass spectrometry, an analytical technique that converts molecules into ions, to see if they could extract metabolites from bone. Using present-day mouse bones, they identified nearly 2,200 metabolites for analysis. The technology also analyzed proteins to detect collagen in some bone samples.

The researchers then turned to animal fossils from 1.3 million to 3 million years ago, collected for prior paleontological research at sites in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa where early humans lived. Focusing on species with living counterparts near these sites today, they used the same analytical methods on fossilized bone fragments from rodents (mouse, ground squirrel, gerbil), as well as an antelope, pig, and elephant.

The analyses yielded thousands of metabolites, many of which were shared with modern-day animals.

The stories fossils tell

Many of the metabolites the researchers found in the fossilized bones represent normal biological functions, including the metabolism of amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. Several pointed to genes associated with estrogen, suggesting that some of the animals were female.

Other metabolites revealed the animals’ response to disease. Notably, in the bone of a 1.8-million-year-old ground squirrel from the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, the researchers found evidence that the squirrel was infected with a parasitic disease known as sleeping sickness in humans, caused by the Trypanosoma brucei parasite and transmitted by the tsetse fly.

“What we discovered in the bone of the squirrel is a metabolite that is unique to the biology of that parasite, which releases the metabolite into the bloodstream of its host. We also saw the squirrel’s metabolomic anti-inflammatory response, presumably due to the parasite,” said Bromage.

The researchers could also deduce what plants the animals ate. While data on plant metabolites are much more limited than those documented in human and animal health, they identified the metabolites of several regionally specific plants, including forms of aloe and asparagus.

“What that means is that, in the case of the squirrel, it nibbled on aloe and took those metabolites into its own bloodstream,” explained Bromage. “Because the environmental conditions of aloe are very specific, we now know more about the temperature, rainfall, soil conditions, and tree canopy, essentially reconstructing the squirrel’s environment. We can build a story around each of the animals.”

The reconstructed environments corroborate what other research has found about these settings millions of years ago—for instance, that the Olduvai Gorge Bed in Tanzania was freshwater woodland and grassland, while the Olduvai Gorge Upper Bed was dry woodlands and marsh. Across all of the sites studied, the conditions in which the animals lived were wetter and warmer than the regions are today.

“Using metabolic analyses to study fossils may enable us to reconstruct the environment of the prehistoric world with a new level of detail, as though we were field ecologists in a natural environment today,” said Bromage.

Reference: “Palaeometabolomes yield biological and ecological profiles at early human sites” by Timothy G. Bromage, Christiane Denys, Christopher Lawrence De Jesus, Hediye Erdjument-Bromage, Ottmar Kullmer, Oliver Sandrock, Friedemann Schrenk, Marc D. McKee, Natalie Reznikov, Gail M. Ashley, Bin Hu, Sher B. Poudel, Antoine Souron, Daniel J. Buss, Eran Ittah, Jülide Kubat, Sasan Rabieh, Shoshana Yakar and Thomas A. Neubert, 17 December 2025, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09843-w

The research was supported by The Leakey Foundation, with additional support for the scanning electron microscope by the National Institutes of Health (S10 OD023659 and S10 RR027990).

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.