This post was originally published on here

Researchers have cracked open salt crystals that formed over 1.4 billion years ago, uncovering trapped air and fluid that offer rare clues about early Earth. These tiny pockets of brine and gas, preserved inside halite crystals in what is now northern Ontario, are providing scientists with the earliest direct evidence of the planet’s ancient atmosphere. The study sheds light on atmospheric conditions at a time when complex life had not yet evolved, revealing new pieces of ancient secrets hidden in salt crystals.

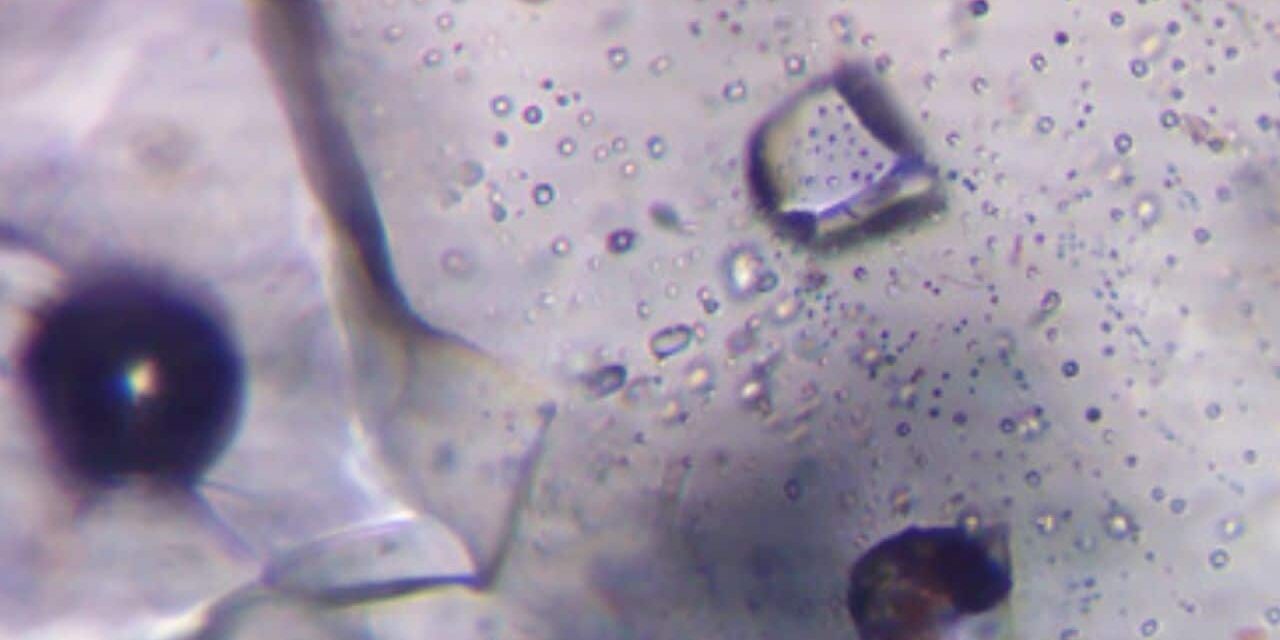

The halite deposits, once part of a shallow, subtropical lake, remained buried and untouched beneath layers of sediment since the Mesoproterozoic era. As the lake dried, salt formed and sealed away microscopic samples of air and brine, effectively freezing them in time.

The newly analyzed samples are helping scientists reconstruct atmospheric conditions from a period known for its geologic and evolutionary stillness.

Breakthrough in analyzing Earth’s oldest atmospheric sample

A team from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, led by graduate researcher Justin Park and guided by Professor Morgan Schaller, Ph.D., conducted the analysis.

Their findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, extend the timeline of direct atmospheric data by more than a billion years.

Park explained that analyzing the contents of the fluid inclusions was technically challenging. These tiny chambers hold both water and gas, and because gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide behave differently in brine than in air, accurate measurements required precise correction.

Using specialized equipment developed in Schaller’s lab, Park succeeded in isolating the gas components with a level of accuracy not achieved before.

Salt crystals unlock ancient secrets of climate and atmosphere

The results showed oxygen levels at about 3.7 percent of what exists today. Although low by modern standards, that amount is enough to support complex multicellular life. Carbon dioxide was found at concentrations ten times higher than today’s levels, suggesting a warmer global climate despite the sun’s reduced brightness at the time.

The findings raise questions about why animal life did not emerge sooner if oxygen levels were temporarily sufficient. Park noted that the data represent only a snapshot in time and may reflect a brief oxygenation event during the so-called “boring billion,” a long period of evolutionary and atmospheric stability.

Schaller added that red algae, which evolved around this time and still contribute heavily to oxygen production, may have played a role in the elevated oxygen levels captured in the sample. He believes the team may have uncovered a rare moment of atmospheric change during an otherwise quiet era in Earth’s history.