This post was originally published on here

At COP30 in Brazil, Australian scientists warned that Antarctica is beginning to experience abrupt, irreversible climate changes.

This dire analysis comes as global average temperatures are increasing past the 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) “point of no return” level outlined by the Paris Agreement.

Those changes include shrinking sea ice, weakening deep-ocean currents, destabilizing ice sheets and transforming ecosystems. Such changes will have consequences for coasts and weather worldwide.

Scientists use abrupt change to describe a climate behavior that moves much faster than normal. These rapid transitions can lock in damage for generations.

Until recently, researchers assumed Antarctica would respond slowly compared with the Arctic, yet new observations show departures from past behavior across the continent.

Antarctica is crossing new lines

The work was led by Prof. Nerilie Abram, a paleoclimate scientist at the Australian Antarctic Division, part of Australia’s national polar program.

Her research combines climate records from ice cores, oceans and ecosystems. They reveal how the Antarctic environment can reorganize when thresholds are crossed.

In a synthesis, her team concluded that abrupt changes are emerging across Antarctic sea ice, oceans, ice sheets and ecosystems.

They argue that decisions taken in this decade will strongly influence whether those changes remain limited or accelerate into effectively irreversible states.

Abrupt change in Antarctica

Abrupt change can mean different things depending on the part of the Antarctic system we are talking about.

A floating ice shelf can fail in days during a heatwave, while sea ice losses and ecosystem reorganizations often take years to appear.

By contrast, loss of grounded ice from the Antarctic ice sheets, and the resulting sea-level rise, will unfold over decades to centuries.

Even so, the critical thresholds that push these systems into new configurations are likely to be crossed within current political planning horizons.

Antarctic sea ice is at record lows

For much of the satellite era, Antarctic sea ice hovered near its long-term average, even growing slightly in the early 2010s.

Since 2016, that pattern has flipped, with repeated record lows that place recent Antarctic sea ice far outside reconstructed twentieth-century variability.

Climate models and observations suggest that subsurface ocean warming and changing winds have pushed the system into a new low sea ice state.

Because the ocean stores so much heat, Antarctic sea ice is expected to keep declining for many decades, even after global temperatures stabilize.

Deep ocean currents are slowing

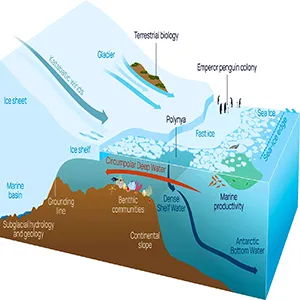

The Antarctic Overturning Circulation – a pattern where cold, salty water sinks and spreads globally – forms when water leaves the continental shelf.

One modeling study found this overturning could slow by 40 percent by 2050, twice the pace expected for its North Atlantic counterpart.

Such a slowdown would reduce the supply of oxygen-rich bottom water and slow the return of deep nutrients that sustain marine life.

Early measurements already show warming and thinning of these dense water masses, signs that the circulation is weakening sooner than expected.

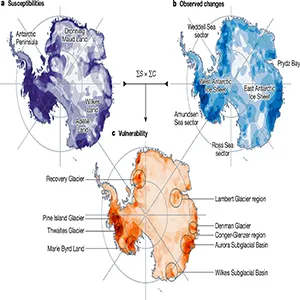

Ice sheets and long-term sea-level rise

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet sits on bedrock lying below sea-level, a configuration that makes it vulnerable to ocean-driven retreat.

Once retreat passes key points, theory and modeling indicate that ice in affected basins will keep flowing into the ocean after temperatures stabilize.

Recent ice sheet simulations suggest that high emissions could cause Antarctica to add 10 feet (3 meters) of sea-level rise, with more committed for millennia.

Lower emissions reduce that long-term commitment, yet they still leave future generations managing rising seas long after this century ends.

Effects on Antarctic land and sea life

Antarctic ecosystems are also changing abruptly, with some land areas greening while others dry out. Sensitive marine communities are also reorganizing as ice conditions transform.

Satellite analyses over the Antarctic Peninsula show vegetation cover increasing more than tenfold since the 1980s, driven largely by expanding, moss-dominated ecosystems.

Extreme drying has damaged long-lived moss beds in some regions, replacing specialist Antarctic species with plants better suited to new conditions.

On the seafloor near retreating ice shelves, filter-feeding communities are giving way to algae-dominated assemblages that thrive in brighter, disturbed water.

Less safe ice for emperor penguins

Emperor penguins depend on stable, land-fast sea ice – sea ice attached firmly to the coast – for almost every part of their life cycle.

In a 2022 study, researchers found that four of five emperor penguin colonies in Bellingshausen suffered breeding failure after sea ice broke up before the fledging period.

Long-term modeling indicates that continued warming and sea ice decline could cut global emperor penguin numbers by more than half.

Field biologists now worry that frequent regional breeding failures, layered on those long-term trends, will push some colonies beyond recovery.

Changes will not stay in Antarctica

The changes unfolding around Antarctica will not stay local, because sea ice, oceans and ice sheets strongly influence global climate patterns.

Losing bright sea ice exposes dark ocean waters, which then absorb more sunlight. This accelerates regional warming and can intensify Southern Hemisphere storms.

Weaker Antarctic Overturning Circulation is expected to alter heat transport between hemispheres, changing rainfall belts and increasing climate variability in many populated regions.

As Antarctic ice loss raises sea-levels over centuries, it will reshape shorelines, increase flooding of coastal infrastructure and strain adaptation capacity worldwide.

Irreversible Antarctic change

Researchers emphasize that the surest way to avoid triggering multiple irreversible Antarctic changes is to cut greenhouse gas emissions deeply this decade.

They stress that emission cuts and ecosystem protections must occur together, since reducing local pollution, fishing and invasive species can preserve remaining resilience.

Governments, businesses and communities are being urged to plan for scenarios where several abrupt Antarctic changes occur together, rather than individually.

“Every fraction of a degree matters,” said Prof. Abram, reflecting on how quickly conditions are changing.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–