This post was originally published on here

Nothing ever feels quite as slow as a minute on the treadmill.

Now, scientists have confirmed that running really does alter how we perceive time – making us overestimate how long we’ve been working out.

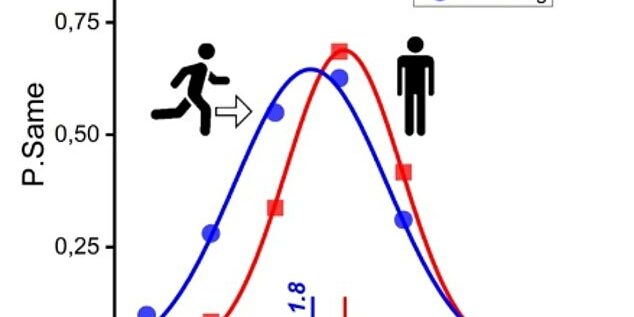

Researchers asked 22 participants to look at an image on a screen for two seconds and then judge whether a subsequent image appeared for the same amount of time.

The task was performed under a range of different conditions including standing still, walking backwards and running on a treadmill.

Analysis revealed that, when running, participants overestimated the passage of time by around nine per cent.

This means that, if you’re out for a jog or getting some miles in at the gym, what feels like a minute would actually correlate to 54.6 seconds.

Previous research has suggested that this phenomenon is down to an increased heart rate during exercise.

But the new study suggests the effect is mainly driven by the large amount of brain power required to manage the balance and coordination required for running.

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports the team, from the Italian Institute of Technology, said: ‘Having an accurate perception of the passage of time is essential for many everyday activities, [but] the subjective feeling of events’ duration often does not match their physical duration.’

This can include everyday experiences like waiting for a bus or for your microwave meal to be ready – both of which typically feel ‘longer’ than they are.

Meanwhile time is also known to ‘fly’, for example when you are having fun or on holiday.

The researchers, led by Tommaso Bartolini, found that while running led participants to overestimate time by nine per cent, walking backwards also caused them to produce a similar distortion of seven per cent.

Although running elevated heart rate substantially more than walking backwards, the time distortion was nearly identical, they said.

This strongly suggests the effect is not driven by physiological exertion – such as heart rate – but instead by the cognitive effort needed to control movement.

‘The results of the current study suggest that we should be very cautious in interpreting perceptual timing biases observed during physical activities as reflecting physiological alterations,’ they wrote.

‘The results also encourage the scientific community investigating time perception… to consider the potential confounding role of cognitive factors implicated in the execution of complex motor routines.’

Previous research has revealed that time really does fly when you’re looking forward to something exciting such as a holiday.

Researchers from Al-Sadiq University in Iraq surveyed more than 1,000 people living in the UK and 600 people in Iraq, asking if they believed Christmas or Ramadan came more quickly each year.

They also measured participants’ memory function and attention to time passing, as well as age, gender and social life.

Analysis revealed that 70 per cent and 76 per cent of people respectively reported that Christmas or Ramadan seemed to come quicker every year.

They were more likely to report this perceived acceleration if they paid more attention to time, were more forgetful of plans, or reported a love of the holiday.