This post was originally published on here

Around 2014, she said, her understanding of shaken baby syndrome began to shift, as more medical professionals who had once endorsed the science openly criticized it. One prominent voice was Dr. Norman Guthkelch, the pediatric neurosurgeon who in 1971 wrote a paper proposing a theory that shaking young children could cause bleeding in the brain.

In a court declaration in 2012 related to a shaken baby case in Arizona, Guthkelch expressed concern about how prosecutors were applying his hypothesis to presume abuse: “I consider that this is a distortion of the article I wrote in 1971, resulting in that article being taken as support of a diagnosis of criminal liability in circumstances which I never envisaged.”

Until his death in 2016, Guthkelch continued to speak out about the misinterpretation of his research.

Turner challenged her own thinking in late 2017, while she was working at a general hospital in Canada. She said she was asked to review the case of a 5-week-old boy who was born with health complications. Other medical professionals saw signs of abuse, implying shaken baby syndrome, she said, but despite feeling “pressured” to join them, she was unconvinced.

“I’m obligated to consider homicide,” Turner said. But “sometimes, you really can’t tell.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics and other associations representing child abuse pediatricians — doctors who specialize in evaluating potential abuse or neglect — defend the shaken baby diagnosis. In 2009, the academy said it was adopting a broader term, “abusive head trauma,” to better explain that other abusive actions beyond shaking can cause head injuries. The academy emphasizes that a child’s health history must be fully evaluated and that a team of experienced professionals should make the complex determination together.

In recent years, Turner, who now runs her own medical and legal consulting firm, has continued to offer second opinions for the prosecution in pediatric abuse cases. But she also serves as an expert witness for the defense when parents face criminal charges.

“I would hope that I’d have the opportunity to right a wrong,” she said.

‘I forgave them’

A pair of medical examiners changed Zavion Johnson’s fate twice — once when their testimony convinced a jury that he shook his baby daughter to death and again more than a decade later, when they reversed themselves and helped set him free.

Johnson was 18, a first-time father, in 2001 when he was caring for his 4-month-old daughter, Nadia, in their Sacramento, California, home while the girl’s mother was at work. He said he had picked the baby up while they were bathing in the shower together, but she slipped from his hands and hit her head on the back of the tub.

He didn’t notice any bleeding or a bump, he said. Hours later, when she stopped breathing, he dialed 911. At the hospital, doctors noted severe head trauma and suspected abuse. Police were called.

Two days later, the girl’s condition worsened. Johnson was cradling Nadia when doctors took her off of life support. On the day of her funeral, police arrested Johnson on charges of murder and assault.

At his 2002 trial, prosecutors relied on testimony from three medical experts, including Dr. Gregory Reiber, a forensic pathologist, and Dr. Claudia Greco, a neuropathologist, to argue that Nadia died from shaking and a deliberate impact.

Reiber, who conducted Nadia’s autopsy, testified that the bleeding behind her eyes was associated with shaken baby syndrome and indicated “that there has been a severe shaking.” Greco testified that an injury in the girl’s cervical spine was the “most convincing evidence” of shaken baby syndrome and that a fall like the one Johnson had described couldn’t have caused such damage.

Johnson was convicted and sentenced to 25 years to life. More than a decade later, the Northern California Innocence Project helped track down the original medical experts and asked whether they would review his case again. Reiber and Greco agreed, and both came to a new finding in early 2017.

“The current reassessment has led me to conclude that accidental injury cannot be excluded,” Reiber wrote in an affidavit recanting his testimony.

Greco wrote in her affidavit that the spinal cord injury she believed was crucial in pointing to shaken baby syndrome “has not been well studied” and that her determination was based on a medical consensus in 2002.

A Sacramento County Superior Court judge vacated Johnson’s conviction, and in early 2018 prosecutors declined to retry him. After having served 16 years of his sentence, he was free.

“It took a lot of courage to say that they were wrong,” Johnson said recently of the medical experts.

Neither Reiber nor Greco could be reached for comment.

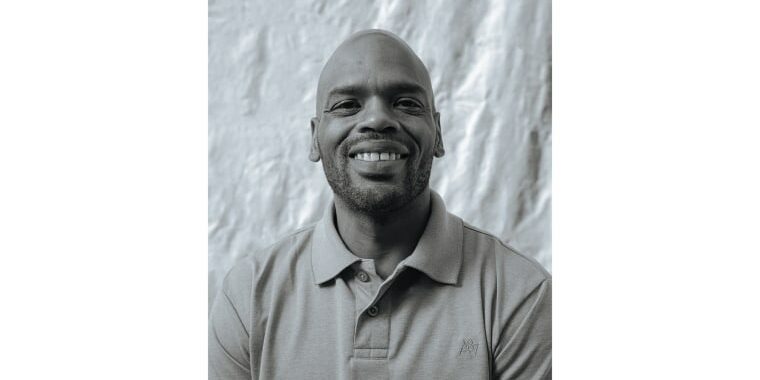

Johnson, now 42 and father to another young daughter, says he feels let down by the justice system when he hears that other parents claiming innocence are still similarly charged.

He’s doing what he can to change that. Not long after his release, he said, he was asked to speak to law enforcement officers and lawyers at a conference in the Bay Area about misleading evidence and false science. Reiber, he said, was also in the room. Later, the men shook hands with tears in their eyes, Johnson recalled.

“I forgave them,” he said of those whose testimony put him behind bars. “My faith allowed me to remove that hate and anger and disappointment I carried for all that time.”

Seeking freedom

Others who maintain their innocence may be closer than ever to their shots at freedom.

In New Jersey, the state Supreme Court’s ruling that expert testimony about shaken baby syndrome is scientifically unreliable could upend an untold number of criminal as well as family court cases, according to the state Office of the Public Defender.

One caregiver who may benefit is Michelle Heale, who in 2015 was sentenced to 15 years in prison for aggravated manslaughter and child endangerment.

Heale was babysitting Mason Hess, her friends’ 14-month-old son, at her Toms River home in 2012, when, she said, the boy began choking on applesauce. She said that she hit him on the back to dislodge the food and that as his head snapped back, he went limp. He was rushed to the hospital and died four days later.

Doctors suspected Mason had been shaken, and Monmouth County prosecutors at Heale’s trial said her version of events was inconsistent. Heale, a mother of young twins at the time, denied she abused him.

“Shaken baby syndrome is a flawed theory that has divided the medical community for many years but has also divided family and friends,” Heale said at her sentencing. “This needs to stop.”

Mason’s parents, Adam and Kellie Hess, supported Heale’s conviction. They declined to comment.

Heale’s attorney is seeking to overturn her conviction and filed a brief based on the state judiciary finding that shaken baby science is unreliable.

The Monmouth County Prosecutor’s Office declined to comment on specifics of the case, but it said in a statement that it believes the state Supreme Court’s ruling has “no legal implications” for Heale’s conviction, which prosecutors contend rests on other evidence that can withstand any further challenges.

As both sides await a judge’s decision, the landmark ruling is already having effects beyond New Jersey.