This post was originally published on here

Researchers found that cold is detected differently in the skin than in internal organs. This split system helps explain why cold air, cold drinks, and cold surfaces create very different sensations.

A research group led by Félix Viana, co-director of the Sensory Transduction and Nociception laboratory at the Institute for Neurosciences (IN), has found that the body does not rely on a single method to detect cold. Instead, the skin and internal organs use distinct molecular mechanisms to sense temperature changes. The Institute for Neurosciences (IN) is a joint research centre of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and Miguel Hernández University of Elche (UMH). This discovery advances scientists’ understanding of thermal homeostasis and sheds light on medical conditions linked to abnormal sensitivity to cold.

The results were recently published in the journal Acta Physiologica. They show that cold perception varies depending on the tissue involved. In the skin, low temperatures are mainly detected by an ion channel called TRPM8, which is especially suited to sensing cool environmental conditions. Internal organs, including the lungs and stomach, depend instead on a different molecular sensor known as TRPA1 to register drops in temperature.

Why Cold Feels Different Inside the Body

These separate sensing systems help explain why cold on the skin feels unlike the sensation of breathing icy air or swallowing a very cold drink. Different tissues activate different biological pathways to detect temperature changes. As Félix Viana explains, “The skin is equipped with specific sensors that allow us to detect environmental cold and adapt defensive behaviors.” He adds: “In contrast, cold detection inside the body appears to depend on different sensory circuits and molecular receptors, reflecting its deeper physiological role in internal regulation and responses to environmental stimuli.”

Comparing Nerves That Detect Cold

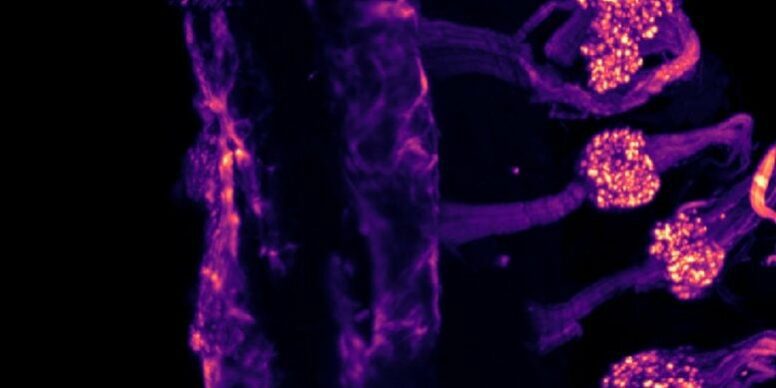

To explore these differences, the researchers conducted experiments using animal models that allowed them to directly observe sensory neurons involved in cold detection. They compared neurons from the trigeminal nerve, which carries sensory information from the skin and the surface of the head, with neurons from the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve serves as the primary sensory connection between the brain and internal organs such as the lungs and digestive tract.

The team studied how these neurons reacted to temperature changes using calcium imaging and electrophysiological recordings. These methods made it possible to track nerve activity in real time. The experiments also included drugs designed to block specific molecular sensors, helping researchers determine which ion channels were responsible for detecting cold in each group of neurons.

Genetic Evidence Confirms Distinct Roles

The study also involved genetically modified mice that lacked either the TRPM8 or TRPA1 sensors. By combining these models with gene expression analyses, the researchers confirmed that each channel plays a different role in cold perception. The findings show that temperature sensing is closely adapted to the specific function of each tissue, with internal organs relying on molecular mechanisms that differ from those used by the skin.

According to Katharina Gers-Barlag, first author of the study, “Our findings reveal a more complex and nuanced view of how sensory systems in different tissues encode thermal information. This opens new avenues to study how these signals are integrated and how they may be altered in pathological conditions, such as certain neuropathies in which cold sensitivity is disrupted.”

Funding and Broader Research Goals

The research was supported by funding from the Spanish National Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation, the Spanish State Research Agency within the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence, and the Valencian Regional Government (Generalitat Valenciana). The work is part of an international project funded by the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP) and coordinated by Viana at the Institute for Neurosciences. This broader effort focuses on understanding the molecular foundations of cold perception in species that have adapted to extreme temperature environments.

Reference: “Transduction Mechanisms for Cold Temperature in Mouse Trigeminal and Vagal Ganglion Neurons Innervating Different Peripheral Organs” by Katharina Gers-Barlag, Ana Gómez del Campo, Pablo Hernández-Ortego, Eva Quintero and Félix Viana, 2 October 2025, Acta Physiologica.

DOI: 10.1111/apha.70111

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.