This post was originally published on here

On the bad days, Millie, a 14-year-old border collie, lies faithfully by Mark Norris’ bed.

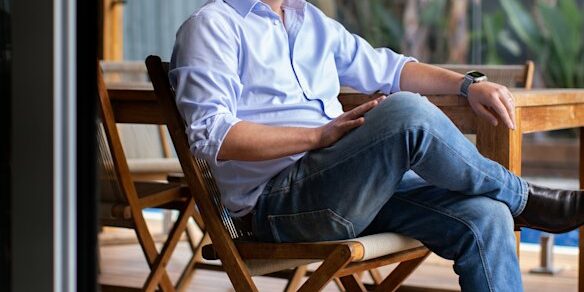

Norris, 52, was leaving a medical appointment in January when he lost all spatial awareness. He couldn’t grab the handle of the car door and, once inside, kept shutting the door on his leg. His wife rushed him to hospital, where an MRI found a massive tumour – the size of two mandarins – pushing his brain to one side.

“They basically put me into surgery within hours, and … I wasn’t expected to survive the operation,” Norris said. “When you’re saying goodbye to your beautiful wife, and two boys as well, that’s pretty hard.”

Norris, from Melbourne, lived. But after six months of intense radiation and chemotherapy, he has finished his treatment for glioblastoma. There’s nothing more doctors can do except wait for the cancer to return.

“To have no options and to know that it’s going to come back, and to have no timeframe around that, it just destroys your family,” he said. “It just destroys you.”

Now, University of Sydney scientists have discovered the genetic mechanism behind how glioblastoma dodges chemotherapy to return in almost all cases, paving the way for research into potential new treatments.

The research, published in Nature Communications earlier this month, found a small population of drug-resistant “persister cells” within tumours that lie dormant during chemotherapy, and then proliferate once the therapy is finished.

The researchers found the growth of these cells is fuelled by a fertility gene called PRDM9. The gene is normally restricted to regulating changes in the chromosomes, but it can be hijacked by glioblastoma cells to act as a tap that provides the cholesterol needed for these cells to survive.

Crucially, they found that switching off this gene immediately after chemotherapy in laboratory models reduced the number of persister cells.

“When you turn off that fertility gene … they basically do not have a supply of cholesterol, and they die,” said Professor Lenka Munoz, the report’s lead author.

The gene had been detected in cancer cells before, but the Sydney Uni team are the first to discover its role in glioblastoma recurrence.

Human trials are years away, but the scientists are working with Australian company Syntara to test potential drug options in animals.

Treatment for glioblastoma has not changed in decades, in which time the median survival rate has hovered at about 15 months.

A number of potential glioblastoma treatments are being trialled in Australia, including an experimental immunotherapy first given to former joint Australian of the Year Richard Scolyer after he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of the cancer in 2023.

Norris, who, alongside Scolyer, is involved in fundraising with Tour de Cure, said he is fortunate to be alive and wants to use his time to accelerate research into better treatments.

“I’m not going to be here to run it through [to find a cure],” Norris said. “So I hope people hear the message and drive that message forward.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.