This post was originally published on here

Repeated, rapid drainages from a meltwater lake on Greenland’s 79°N Glacier are exposing how warming-driven fractures and hidden channels may be pushing the glacier into an unfamiliar and potentially unstable state.

Since the mid-1990s, the Greenland ice sheet has steadily lost mass, and only three floating glacier tongues remain today. One of them, Nioghalvfjerdsbræ, also known as the 79°N Glacier, is already beginning to show signs of instability. While warmer ocean water is increasingly eroding the ice from below, meltwater flowing across the glacier’s surface is becoming an equally important factor.

In a recent study, scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute examined the formation and evolution of a large meltwater lake on the surface of the 79°N Glacier. Covering an area of 21 km2, the lake developed as a result of global warming. Over time, the researchers found that it triggered enormous fractures in the ice and that the draining water was strong enough to lift parts of the glacier. The results of the study were published in the journal The Cryosphere.

The lake was first detected in observational data from 1995.

“There were no lakes in this area of the 79°N Glacier before the rise in atmospheric temperatures in the mid-1990s,” as Prof. Angelika Humbert, glaciologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) stated. “From the time of its formation in 1995 until 2023, the lake’s water repeatedly and abruptly drained through channels and cracks in the ice, causing massive amounts of fresh water to reach the edge of the glacier tongue towards the ocean.”

Altogether, the researchers documented seven major drainage events. Four of these occurred within the past five years.

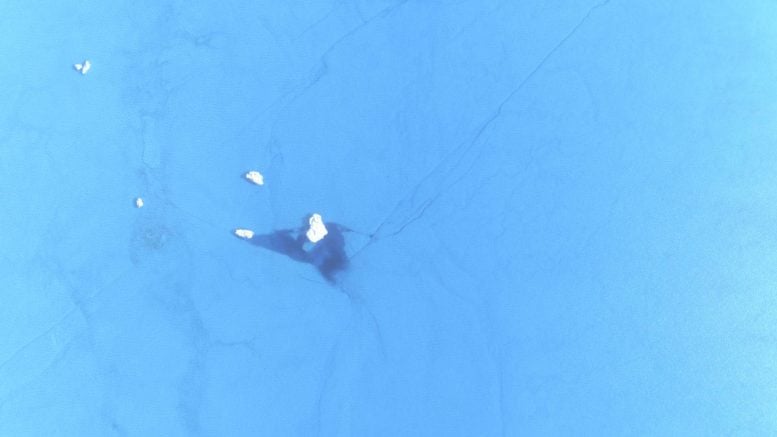

“During these drainages, extensive triangular fracture fields with cracks in the ice formed from 2019 onwards, which are shaped differently from all lake drainages I have seen so far,” Angelika Humbert marvels. Some of these cracks form channels with openings several dozen meters wide (moulins).

Water flows through these moulins also after the main drainage of the lake, meaning that within hours, a huge amount of water reaches the base of the ice sheet. “For the first time, we have now measured the channels that form in the ice during drainage and how they change over the years.”

Ice as Both Fluid and Elastic Solid

After the lake had formed in 1995, its size decreased over time, with the first cracks appearing. In recent years, the drainage has occurred at increasingly shorter intervals.

“We suspect that this is due to the triangular moulins that have been reactivated repeatedly over the years since 2019,” says Angelika Humbert.

The material behavior of the glacier plays a role here: on the one hand, the ice behaves like an extremely thick (viscous) fluid that flows slowly over the substrate. At the same time, however, it is also elastic, allowing it to deform and return to its original shape, similar to a rubber band.

The elastic nature of the ice is what allows cracks and channels to form in the first place. On the other hand, the creeping nature of the ice helps channels inside the glacier to close again over time after the drainage has taken place.

“The size of the triangular moulin fractures on the surface remains unchanged for several years. Radar images show that although they change over time inside the glacier, they are still detectable years after their formation.” This data also reveals that there is a network of cracks and channels, meaning that there is more than one way for the water to escape.

Meltwater is lifting the glaciers

The researchers were able to see shadows along the cracks in some aerial photographs. “In some cases, the ice at the fracture surfaces has also shifted in height, as if it were raised more on one side of the moulin than on the other,” as Angelika Humbert related.

The largest shift is encountered directly in the lake, which is due to the enormous masses of water that have entered the cracks beneath the glacier and formed a subglacial lake there. Radar images from inside show that a blister has apparently formed on this lake beneath the ice, pushing the glacier upwards at this point. Even more than 15 years after the first drainage, the cracks are still visible on the surface.

Observations, Models, and Open Questions

In conducting their study, the researchers analyzed data from various measurements. Using satellite remote sensing data and data from airborne surveys, they were able to investigate how the lake fills and drains and the paths of the water within the glacier. Viscoelastic modelling enabled them to determine whether and how drainage paths close over time.

The results raise a crucial question: Have the frequent drainages forced the glacier system into a new state, or can the system (still) return to a normal winter state in spite of these extreme amounts of water?

“In just ten years, recurring patterns and regularity have developed in the drainage, with massive and abrupt changes in meltwater inflow on a timescale of hours to days,” says Angelika Humbert. “These are extreme disturbances within the system, and it has not yet been investigated whether the glacial system can absorb this amount of water and is able to influence the drainage itself.”

The study provides important data for integrating cracks into ice sheet models and researching how they form and influence the glacier. AWI researchers are working closely with scientists from TU Darmstadt and the University of Stuttgart on the modelling.

Understanding and taking the behavior and effects of cracks in the glacier into account is particularly important when regarding the development of the lake on the 79°N Glacier: due to the advancing warming of the atmosphere, the fracture surfaces have been occurring further and further up the slope, impacting an increasingly larger area of the glacier.

Reference: “Insights into supraglacial lake drainage dynamics: triangular fracture formation, reactivation and long-lasting englacial features” by Angelika Humbert, Veit Helm, Ole Zeising, Niklas Neckel, Matthias H. Braun, Shfaqat Abbas Khan, Martin Rückamp, Holger Steeb, Julia Sohn, Matthias Bohnen and Ralf Müller, 14 August 2025, The Cryosphere.

DOI: 10.5194/tc-19-3009-2025

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.