This post was originally published on here

– Advertisement –

BEIJING, Dec 29 (APP):Since February this year, a quiet but significant breakthrough unfolded in several of Beijing’s top neurosurgical hospitals. Working with the Chinese Institute for Brain Research, Beijing (CIBR) and NeuCyber NeuroTech, teams at Peking University First Hospital, Xuanwu Hospital and Tiantan Hospital completed six successful semi-invasive brain–computer interface (BCI) implantations.

More than 98 percent of neural channels remained functional after surgery, and signal recording remains at high quality level for already over 10 months. Most strikingly, a patient with paraplegia from a spinal cord injury for more than five years regained the ability to stand and walk with the aid of axillary crutches after rehabilitation training driven by the NeuCyber Matrix BMI System (Beinao-1).

The cases offer a glimpse into how China’s BCI sector is moving beyond laboratory research and into early-stage clinical application, at a moment when the technology has been formally elevated to a national industrial priority.

A coordinated national push

On July 23, 2025, seven central government bodies, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and the National Development and Reform Commission, the National Health Commission, and the National Medical Products Administration, jointly released a set of guidelines aimed at promoting the innovative development of the BCI industry. The document designates BCIs as a strategic “future industry” and lays out a phased development roadmap through 2030.

The country seeks to achieve key technological breakthroughs in the industry by 2027, alongside the establishment of advanced technology, industry and standards systems, according to the guidelines.

Specifically, the guidelines call for the accelerated adoption of BCI products across sectors such as industrial manufacturing, health care and consumption by 2027, and for the development of new scenarios, business models and formats.

By 2030, the country should strengthen its BCI innovation capabilities significantly, establish a safe and reliable industrial ecosystem, and cultivate two to three globally influential leading enterprises, reads the guidelines.

Industry analysts see the policy as a signal that BCIs in China are transitioning from frontier research projects into an organized industrial track with regulatory oversight, clinical pathways, and long-term planning, CEN reported.

What BCIs actually decode

Public perceptions of BCIs often swing between extremes, that is, visions of effortless “mind reading” or fears of dystopian “mind control.” In practice, the technology occupies a more constrained, but still transformative, middle ground.

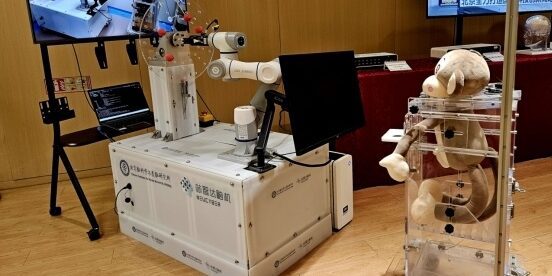

At a technical level, a brain–computer interface translates neural electrical activity into interpretable outputs, such as cursor movement, robotic control, or synthesized speech. Every human action, from grasping a cup to forming a word, is associated with coordinated activity across distributed neural populations.

In theory, comprehensive recording of brain activity could enable precise decoding of mental states. In reality, today’s most advanced invasive BCIs typically record signals from hundreds to just over a thousand neural channels, while the human brain contains roughly 86 billion neurons, noted Dr. Minmin Luo, director of CIBR. This mismatch defines a fundamental constraint of the field.

Non-invasive approaches, including electroencephalography (EEG) devices that collect brain signals from outside the skull, face additional challenges. Signals are attenuated by the skull and contaminated by muscle and motion artifacts. These systems can reliably detect coarse brain states – attention, fatigue, or sleep – but struggle to decode fine motor intentions or language generation.

As a result, the highest-performing BCIs remain invasive, placing electrodes on or within the cortex to achieve sufficient spatial and temporal resolution. Even then, what is decoded is not abstract thought, but specific neural patterns associated with trained, well-defined tasks.

Why medicine comes first

These technical limits largely explain why medical rehabilitation has emerged as the leading domain for BCI deployment. Clinical applications are tightly constrained: patient needs are clear, outcomes are measurable, and ethical oversight is strict.

In October 2023, a joint team from Tsinghua University’s medical faculty and Xuanwu Hospital conducted the world’s first clinical trial of a wireless, minimally invasive BCI. The participant, paralyzed for 14 years following a traffic accident, regained the ability to perform tasks such as independently drinking water after three months of rehabilitation training, achieving more than 90 percent accuracy in brain-controlled grasping.

Internationally, similar momentum is visible. In January 2024, Neuralink completed its first human implantation in the United States, with the participant later demonstrating the ability to control a computer cursor using intention alone. For the first time, BCIs entered public discourse not as speculative concepts, but as reproducible, regulated medical technologies.

BCI research is also expanding beyond motor restoration.

Clinical urgency and practical limits

Globally, many live with spinal cord injuries, stroke-related disabilities, or neurodegenerative diseases for which existing treatments offer limited benefit. In China alone, several million people in China suffer from paralysis caused by spinal cord injury, with tens of thousands of new cases added every year, according to the World Health Organization’s regional estimates.

This scale of unmet clinical need explains why BCIs are moving from feasibility demonstrations toward validation of long-term safety and effectiveness. Devices that can demonstrate durable functional improvement under strict medical regulation are also those most likely to gain public trust and regulatory approval.

Beyond healthcare, consumer-facing brain devices are beginning to appear in areas such as brain-controlled gaming, immersive education, and attention training. These applications prioritize accessibility over precision and rely primarily on non-invasive signals. Their value lies in narrow, context-specific use cases, not in decoding complex intentions or internal thoughts.

The distinction is critical. Medical BCIs advance because they operate within biological, regulatory, and ethical constraints. Consumer applications succeed only when their limitations are clearly acknowledged.

Engineering and ethical boundaries

Even invasive BCIs face unresolved engineering challenges. Neural signals drift over time, meaning patterns recorded today may differ weeks or months later. For young patients with spinal cord injuries or neurodegenerative diseases, devices must remain stable and functional for decades.

Long-term biocompatibility, mechanical durability, and surgical safety are therefore as important as decoding accuracy, Luo told us. A system that performs well for months but degrades over years is not clinically viable.

Data scarcity further complicates progress. According to recent clinical trial data, around 200 people worldwide have received invasive BCIs. However, recording methods, electrode designs, and behavioral tasks continue to vary widely, limiting the large-scale data aggregation needed for universal decoding models.

Ethical concerns are equally significant. Neural data can reveal disease risk, cognitive decline, and aspects of personal identity. Informed consent, anonymization, and strict governance are essential. Certain neural information, particularly signals related to intent and identity, must be treated as inviolable mental privacy.

In this context, the greatest risk is not mind control, but overgeneralization, mistaking narrowly successful demonstrations for broad access to the human mind.

Diverging national paths

Different countries are approaching brain–computer interface governance through distinct institutional paths, reflecting broader differences in how emerging technologies are regulated.

In the United States, development is driven primarily by private companies leveraging the FDA’s “Breakthrough Devices Program” to accelerate clinical translation. While this ecosystem excels in system integration, custom neural chips, and venture capital scale, governance is now expanding beyond medical safety.

With the introduction of the Management of Individuals’ Neural Data (MIND) Act of 2025, US policymakers are actively establishing new frameworks to address neuro-rights, specifically focusing on neural data privacy and mental liberty.

China, by contrast, is pursuing a state-led coordinated approach that integrates policy planning, clinical validation, and industrial clusters. Following the 2025 multi-ministry plan, China is accelerating the development of a full industrial chain, from high-performance electrodes to BCI-specific chips.

Supported by strong neurosurgical capacity and large patient populations, Chinese research teams are exploring multimodal technical routes (including invasive, non-invasive, and interventional BCI), with a strategic emphasis on restorative medical outcomes and national ethical standards for responsible innovation.

Europe has taken a more precautionary, ethics-first approach. Rather than prioritizing rapid commercialization, regulators and research institutions emphasize human dignity, informed consent, and data protection, often embedding BCI research within broader artificial intelligence and biomedical ethics regimes. While this approach may slow large-scale deployment, it has positioned ethical governance as a central pillar of neurotechnology development.

A quieter future

According to a report titled Brain Computer Interface Market Size, Share and Trends 2025 to 2034 by Precedence Research, the market for brain technology was worth about $2.6 billion last year and is expected to rise to $12.4 billion by 2034. But for many, this technology is about much more than cash.

As brain–computer interfaces move from laboratories into hospitals, their trajectory is becoming clearer. They are not tools for reading minds or rewriting consciousness. They are instruments for restoring functions lost to injury or disease, operating within strict biological and ethical limits.

The future of BCIs will be shaped less by how much of the brain can be decoded, and more by how carefully societies decide where, and for whom, these technologies should be used.

In that sense, the most important questions raised by BCIs are not about machines, but about what it means to intervene responsibly in the human condition.