This post was originally published on here

They’re some of the most sterile places on Earth – but scientists have discovered dozens of new bacterial species inside NASA’s cleanrooms.

These facilities are ultra-sanitised, highly controlled spaces where spacecraft and sensitive instruments are built and tested.

They are designed to prevent any form of contamination and to stop unwanted microbes from hitching a ride to other planets.

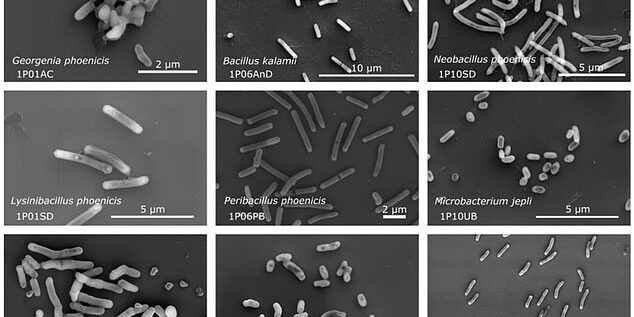

So experts were left stunned after finding 26 tiny living organisms – all previously unknown bacterial species – in the Kennedy Space Center cleanrooms in Florida.

Despite stringent measures including filtering air, the strict regulation of temperature and humidity and the use of harsh chemical detergents, these microbes have somehow managed to survive.

‘It was a genuine “stop and re-check everything” moment,’ Alexandre Rosado, a professor of Bioscience at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia, told Live Science.

Recent analysis of these microbes has shed light on how they can live – and even thrive – in one of the harshest man-made environments on Earth.

And it turns out they have genes that help them resist the effects of radiation and even repair their own DNA.

The main goal of cleanrooms is to stop Earth’s organisms contaminating other planets that could potentially contain life.

They also play a crucial role in protecting Earth from potential alien hitchhikers in returned samples.

However, ‘cleanrooms don’t contain “no” life’, Professor Rosado said. ‘Our results show these new species are usually rare but can be found.’

The new species were identified lurking in cleanrooms where NASA assembled its Phoenix Mars Lander in 2007.

They were collected and preserved at the time, and recent advances in DNA technology has allowed scientists to properly analyse them.

The findings, published in the journal Microbiome, read: ‘Maintaining the biological cleanliness of NASA’s mission-associated cleanrooms, where spacecraft are assembled and tested, is critical for planetary protection.

‘Even with stringent controls such as regulated airflow, temperature management and rigorous cleaning, resilient microorganisms can persist in these environments, posing potential risks for space missions.’

The next step, experts said, is to figure out whether any of these tiny organisms could have potentially tolerated conditions during a journey to Mars’ northern polar cap, where Phoenix landed in 2008.

Professor Rosado said several species do carry genes that may help them adapt to the stresses of spaceflight.

But their survival would depend on how they handle the harsh conditions of the journey and on the Red Planet itself, including exposure to vacuum, deep cold and high levels of UV.

To explore this further, the team plan to test the microbes inside a ‘planetary simulation chamber’ that could reveal whether they could survive a trip through space.

One is currently being built at JAUST, with its first experiments expected to commence in early 2026.

The team said that beyond space exploration, these microbes hold ‘immense promise’ for biotechnology as their resistance to radiation and chemical stressors could drive innovations in medicine, pharmaceuticals and the food industry.