This post was originally published on here

By Pat Sheil

SCIENCE

Alchemy

Philip Ball

Yale University Press $61.95

Towards the end of Philip Ball’s marvellous book on the history of alchemy he tells the story of pioneering nuclear physicist Ernest Rutherford being told in 1901, by his co-worker Frederick Soddy, that the decay of radioactive thorium into radon gas meant they had witnessed the transmutation of one chemical element into another.

“For Mike’s sake, Soddy, don’t call it ‘transmutation’,” Rutherford cried. “They’ll have our heads off as alchemists!”

Now, watching thorium transforming itself into radon isn’t exactly turning base metals into gold, the Holy Grail of alchemy for centuries, but in 1980 the deed was eventually done. A few thousand atoms of gold were created by bombarding bismuth atoms with carbon 12.

A few thousand atoms would not have impressed the 16th-century Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II, a staggeringly wealthy patron of alchemists, astrologers, astronomers, artists and radical thinkers of every stripe. Rudolph was an ineffective and negligent monarch, partly responsible for the ghastly wars that convulsed Europe for decades after his death, but his lavish court encapsulated many of the threads of Ball’s fascinating tale.

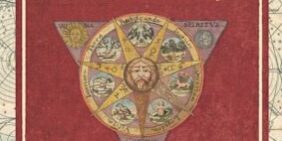

Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II as a patron of alchemists, astrologers, astronomers, artists, and radical thinkers.Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Alchemy is subtitled An Illustrated History of Elixirs, Experiments, and the Birth of Modern Science, and while Ball traces alchemy’s origins from Ancient Egypt, China, Greece and the Middle East, it is in medieval and Renaissance Europe that we meet the most remarkable practitioners of chrysopoeia (a glorious word for the artificial creation of gold).

The author writes with elegant economy as he sketches the characters who devoted their lives to alchemy over the centuries, and a roll call of the brilliant natural philosophers and outright charlatans who made their way to Rudolph’s palaces gives an insight into his thesis: these men (for men they mostly were), whatever we might make of them today, were creatures of their times.

Since the mid-19th century, alchemy has been a byword for greed, superstition and chicanery. Yet while there has been no shortage of quacks and fraudsters besmirching its reputation, there were just as many making genuine, if often misguided, inquiries into the workings of nature. Alchemy challenges the reader to imagine how any one of us might have undertaken such investigations 500 years ago, with only the teachings of the Church and the ancient Greeks to guide us.

Ball reminds us, too, that the quest for the philosopher’s stone, or whatever mechanism one hoped would turn lead or tin into untold riches, was just one of countless experiments undertaken by these foolhardy investigators.

Foolhardy because alchemy, in any of its forms – whether seeking gold, mixing cosmetics, preparing medicines or simply blowing a better glass alembic – was dangerous work. Quite apart from the heat of furnaces required to melt metals and glass, alchemic recipes often called for terminally toxic ingredients. Mercury, as one of the essential elements of countless alchemic preparations, is, of course, a deadly poison. One that, ironically enough, kills thousands of Third World gold miners every year.

An artwork by Joan Galle depicting an alchemist and his assistants.Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Add lead, arsenic, antimony – and the hazards of poorly ventilated workshops either stinking of sulphur or brimming with undetectable carbon monoxide – and it is surprising how many alchemists lived long enough to publish their theories and recipes.

Some alchemical writings were to have immense influence for centuries, among them the work of Swiss physician Paracelcus, English alchemist and astrologer George Ripley (compiler of the astonishing, six-metre-long Ripley Scroll) and his mysterious countryman, mathematician, bibliophile and magus John Dee, who fled the England of Bloody Mary to wander central Europe. He inevitably found favour with Emperor Rudolph II before returning to the court of Elizabeth I as her astronomer and astrologer, roles seen as complementary since antiquity.

Ball masterfully juggles his cast of seers, seekers, sages and scientists. The court of Rudolph II welcomed the likes of astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, who perfected the heliocentric orbits of the planets, along with Dee and other occultists. He repeatedly reminds us that most of these fellows, apart from the shameless charlatans promising endless lucre to avaricious princes, were among the intellectual elite of their times.

Robert Boyle and Issac Newton, two of the heroes of modern science, saw no logical contradiction in their experiments with alchemy. Science does win out in the end, of course. As Arthur C. Clark put it in 1962, “Any sufficiently advanced technology will be seen as magic”, and Rudolph II and his courtiers would not have recognised antibiotics or television as the work of mere mortals.

But, for good or ill, the foundations of everything we take for granted in 2025 slowly emerged and evolved from the fascinating, often delusional but relentless tinkering and musings of these pioneering experimentalists.

Alchemy is a wonderful and beautifully illustrated guidebook to a strange land, compiled with erudition, enthusiasm, empathy and common sense.