This post was originally published on here

Early humans may have feasted on Neanderthal children 45,000 years ago, according to a grisly new study.

Researchers have analysed bones found in a Belgian cave where cannibalism was known to have taken place.

They revealed the six victims were children and young women who may have been cooked before being eaten.

And while the identity of the cannibals remains unknown, there’s the possibility it could have been early Homo sapiens preying on rival Neanderthals, the scientists said.

The Goyet caves, first excavated in the 19th century, have yielded the most important collection of Neanderthals in northern Europe.

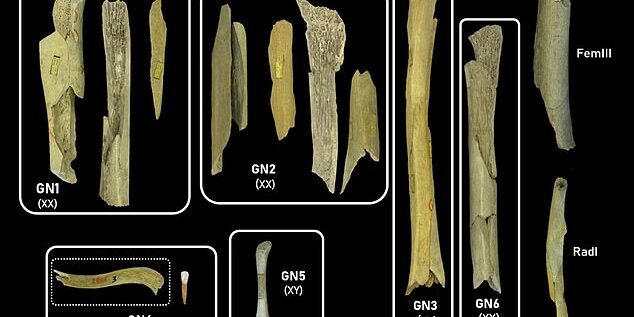

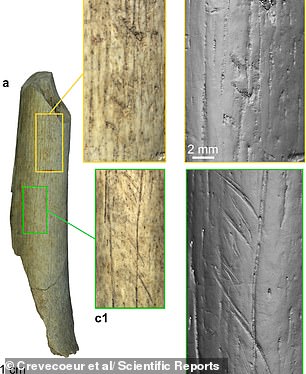

A 2016 study showed that a third of the 101 bones uncovered there – mainly from the lower limbs – showed traces of cannibalism with cut marks and notches.

‘The composition – women and children, without adult men – cannot be coincidental: it reflects a deliberate selection of victims by the cannibals,’ Isabelle Crevecoeur, research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, said.

‘The fact that the cannibalized women and children came from elsewhere indicates “exocannibalism” – the consumption of individuals belonging to one or more external groups.’

The team combined genetics, isotope analysis and a detailed study of morphology to sketch a biological portrait of the cannibalised individuals.

Analysis of their DNA showed that the four adult or adolescent victims were women of small stature – around 1.5m tall – who were not from the local area. There were also two male children, one infant and one child between 6.5 and 12.5 years old.

A close look at their remains also showed evidence of circular impacts, made to break the bone in order to extract the highly calorific marrow.

All these indications have led to the conclusion that these Neanderthal women and children from elsewhere were brought to Goyet and consumed, the researchers said.

This type of behaviour is already observed in chimpanzees, with the purpose of weakening a neighbouring population or asserting territorial control.

‘The Goyet site provides food for thought’, Patrick Semal, another of the study’s authors from the Royal Belgian Institute of National Sciences, said.

‘The results indicate possible conflicts between groups at the end of the Middle Paleolithic, a period when Neanderthal groups were dwindling and Homo sapiens was in full expansion in Northern Europe.

‘We cannot rule out that the cannibals were Homo sapiens, but we rather think they were Neanderthals. Some of the fragmented bones were also used to retouch stone tools, and this practice is known mainly among Neanderthals.’

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports the team said: ‘At Goyet, the unusual demographic mortality profile of the cannibalised individuals (adolescent/adult females and young individuals) cannot be considered natural.

‘Nor can it be explained solely by subsistence needs, especially given the abundant associated faunal remains that show similar butchery marks.

‘At a minimum, it suggests that weaker members of one or multiple groups from a single neighbouring region were deliberately targeted.

‘Although the precise causes of inter–group tensions in Pleistocene contexts remain difficult to establish, the regional chronocultural context is consistent with the hypothesis that conflict between groups played a role in the accumulation of the cannibalised individuals at Goyet.’

They said that even though Homo sapiens are not yet documented in the region at the same time as Neanderthals, there is evidence they were present at around the same time some 600km to the east in Germany.

And while the Homo sapiens predator hypothesis ‘cannot be entirely ruled out’, they said the most likely explanation for the cannibalism is conflict between Neanderthal groups.

Scientists have long speculated what caused the downfall of the Neanderthals, but a recent study suggests they never truly went extinct at all.

Scientists in Italy and Switzerland claim the ancient group of archaic humans didn’t experience a ‘true extinction’ because their DNA exists in people today.

Over as little as 10,000 years, our species, Homo sapiens, mated and produced offspring with Neanderthals as part of a gradual ‘genetic assimilation’.

‘Our results highlight genetic admixture as a possible key mechanism driving their disappearance,’ experts said.

Our species, Homo sapiens, existed at the same time as Neanderthals for several thousand years, before we became dominant.

This ancient relative had large noses, strong double–arched brow ridge and relatively short and stocky bodies, skeletal evidence shows.