This post was originally published on here

A new study suggests dopamine may not directly control how fast or forcefully movements are made, challenging a long-standing view in neuroscience.

New research led by McGill University is questioning a widely held idea about how dopamine influences movement, a finding that may change how scientists approach treatments for Parkinson’s disease.

The study, published in Nature Neuroscience, shows that dopamine does not directly control the speed or strength of individual movements, contrary to previous assumptions. Rather, the chemical appears to provide the essential background conditions that allow movement to happen in the first place.

“Our findings suggest we should rethink dopamine’s role in movement,” said senior author Nicolas Tritsch, Assistant Professor in McGill’s Department of Psychiatry and researcher at the Douglas Research Centre. “Restoring dopamine to a normal level may be enough to improve movement. That could simplify how we think about Parkinson’s treatment.”

Dopamine plays a key role in motor vigor, or the ability to move quickly and with force. In people with Parkinson’s disease, the gradual loss of dopamine-producing neurons leads to slowed motion, tremors, and problems with balance.

Levodopa is the most commonly used medication for Parkinson’s disease and can improve a patient’s ability to move, yet scientists still do not fully understand the mechanism behind its benefits. More recently, sensitive technologies have picked up rapid dopamine surges that occur during movement, prompting many researchers to suspect these brief spikes help determine motor vigor.

The new study points in the opposite direction.

“Rather than acting as a throttle that sets movement speed, dopamine appears to function more like engine oil. It’s essential for the system to run, but not the signal that determines how fast each action is executed,” said Tritsch.

Measuring dopamine in real time

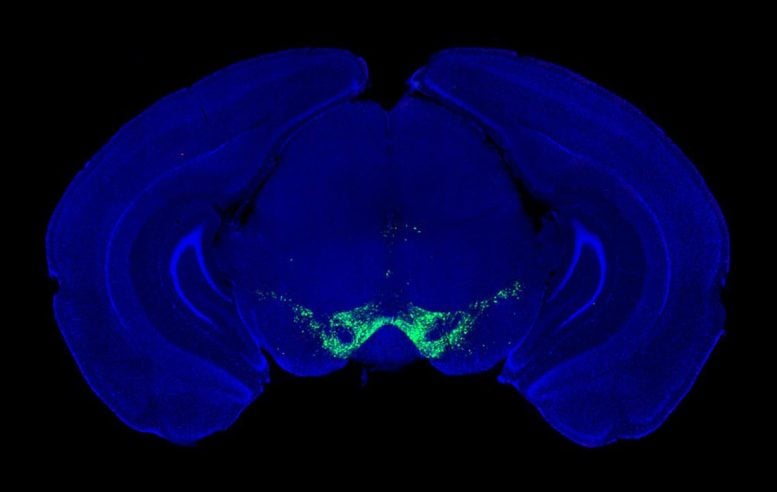

The researchers measured brain activity in mice as they pressed a weighted lever, turning dopamine cells “on” or “off” using a light-based technique.

If fast dopamine bursts did control vigor, changing dopamine at that moment should have made movements faster or slower. To their surprise, it had no effect. In tests with levodopa, they found the medication worked by boosting the brain’s baseline level of dopamine, not by restoring the fast bursts.

A more precise target for treatment

More than 110,000 Canadians live with Parkinson’s disease, a number projected to more than double by 2050 as the population ages.

A clearer explanation for why levodopa is effective opens the door to new therapies designed to maintain baseline dopamine levels, the authors note.

It also encourages a fresh look at older therapies. Dopamine receptor agonists have shown promise but caused side effects because they acted too broadly in the brain. The new finding offers scientists a sense of how to design safer versions.

Reference: “Subsecond dopamine fluctuations do not specify the vigor of ongoing actions” by Haixin Liu, Riccardo Melani, Marta Maltese, James Taniguchi, Akhila Sankaramanchi, Ruoheng Zeng, Jenna R. Martin and Nicolas X. Tritsch, 10 November 2025, Nature Neuroscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02102-1

The study was funded by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.