This post was originally published on here

Archaeologists have unearthed the world’s earliest intentional cremation of an adult human known till date in Malawi, a discovery that raises new questions about early funeral rituals.

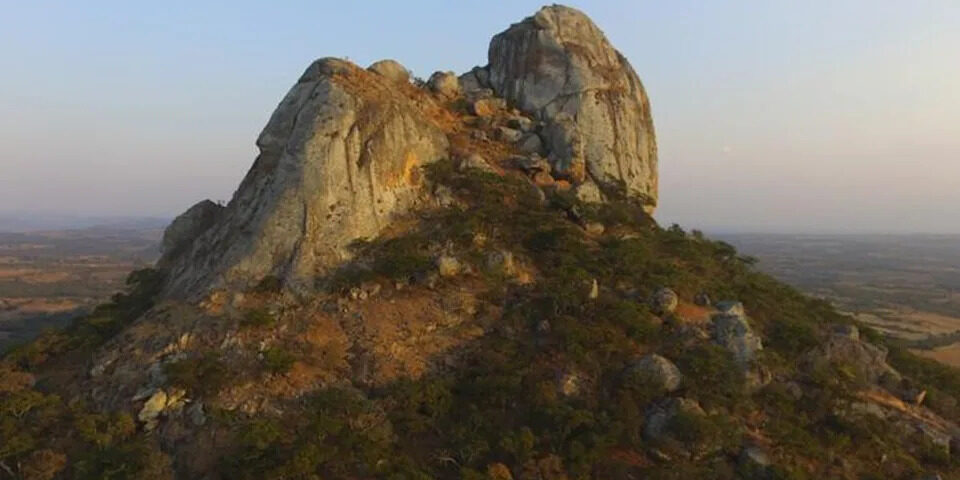

Tucked at the base of a granite hill rising several hundred feet from the surroundings is the Hora 1 archaeological site in Malawi, known for decades.

Here, scientists unearthed prehistoric ash about the size of a queen bed containing the fragmented remains of a woman “just under five feet tall”, guarded from the elements for thousands of years.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“With finding this particular funeral pyre, I think we just got lucky because it’s in a shelter and the rain doesn’t fall directly on it and there’s good preservation of bones,” archaeologist Jessica Thompson from Yale University tells The Independent.

The prehistoric ash itself was found “cemented”, she says.

“It wasn’t rain, but the soil moisture hardened the ash and made it hard to excavate, but it was also helpful since termites tend to burrow through bones, but at this site the cemented layer prevented that,” Dr Thompson says.

“You can see here that the mites try to go in, and then they’re like ’no!’ and they don’t go through the cemented layer,” she says, adding that it was a “very interesting, fortunate set of preservation”.

Hora Mountain from afar (Jacob Davis)

Until now, the oldest known deliberate cremations, which have been confirmed by the presence of a pyre, have dated back to roughly 3,300 years ago.

Advertisement

Advertisement

In comparison, the cremation at the Hora 1 archaeological site in Malawi was a meticulously planned event performed 9,500 years ago by African hunter-gatherers, researchers say.

“This is a very unusual funeral treatment. From this time period, we don’t find a lot of burned bodies so it’s pretty shocking,” anthropologist Jessica Cerezo-Román tells The Independent.

“Also why this person? Was she significant in life or in death? We don’t know that yet,” said Dr Cerezo-Román, another author of the study from the University of Oklahoma.

Reconstructed events of pyre (Patrick Fahy)

Studying funeral rituals of prehistoric societies offers several insights about the way people treated each other during their lifetimes.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Who the person is and how they were treated when they lived influences how they are treated in their funerals,” Dr Cerezo-Román says.

At the Malawi site, scientists found that the small adult female’s remains bear marks of manipulation, indicating her body was carefully cremated prior to decomposition, probably within a few days of her death.

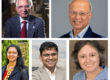

Hora site from air (Jacob Davis)

The findings confirm that these ancient African hunter-gatherers undertook elaborate, communal mortuary practices.

“These practices emphasise complex mortuary and ritual activities with origins predating the advent of food production, and challenge traditional assumptions about community-scale cooperation and memory-making in tropical hunter-gatherer societies,” write researchers in the study published in the journal Science Advances.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“These hands-on manipulations, cutting flesh from the bones and removing the skull, sound very gruesome, but there are many reasons people may have done this associated with remembrance, social memory, and ancestral veneration,” explains

Hora 1 site under excavation (Jessica Thompson)

Although burned human remains have been found previously dating to as early as about 40,000 years at Lake Mungo in Australia, intentionally built pyres using combustible fuel appear in archaeological record only until about 30,000 years later.

The practice of cremation is more common among food-producing societies, which possess more complex technology and engage in more elaborate mortuary rituals.

However, the practice is very rare among ancient and modern hunter-gatherers, partly because pyres require a huge amount of labor, time, and fuel to transform a body into fragmented bone and ash, Dr Cerezo-Román said.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Building the pyre found at the Hora 1 site would have required gathering at least 30 kg of deadwood and grass, pointing toward a significant communal effort, according to the study, which suggests the blaze likely reached temperatures greater than 500C.

Researchers recover remains (Grace Veatch)

The finding sparks a re-think of how archaeologists view group labour and ritual in ancient hunter-gatherer communities.

It also raises several questions about the sudden change in mortuary practices by hunter-gatherers in Malawi 9,500 years ago, who had typically been burying the dead.

Researchers found that the hunter-gather society revisited the location afterwards and built more large fires, indicating they maintained a longer tradition based on their shared memory of the woman’s cremation.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Why was this one woman cremated when the other burials at the site were not treated that way?” asks Dr Thompson.

“There must have been something specific about her that warranted special treatment,” she says.