This post was originally published on here

The makers of Guinness long ago claimed that it was good for you and anyone with a television set has been aware, since at least the 1970s, that Heineken supposedly refreshes the parts that other beers cannot reach. But no one until now has claimed that a pint could save your life.

Then came Chris Buck, a virologist at the National Cancer Institute, who is also an enthusiastic home brewer. Dr Buck believes he has created the world’s first beer vaccine. He brewed the first batch last summer using a yeast modified to contain a vaccine protein. It was a Lithuanian-style farmhouse ale that was awfully drinkable, and also appeared to immunise him against a virus linked to certain cancers.

“It was one of the best homebrews I ever made,” he said. He drank about two pints a day for the next four days and then conducted regular blood tests in the months that followed.

• Sign up for The Times’s weekly US newsletter

These tests suggested he had developed antibodies against two types of BK polyomavirus thought to cause certain types of bladder cancer, he said.

In Buck’s view, this only the start of what a beer could do. “This one vaccine is just proving the principle,” he said. “Next on the agenda is Covid and flu and probably herpes viruses and adenovirus [associated with mild colds and flu] … Anything that is a common-cold virus is in our crosshairs now.”

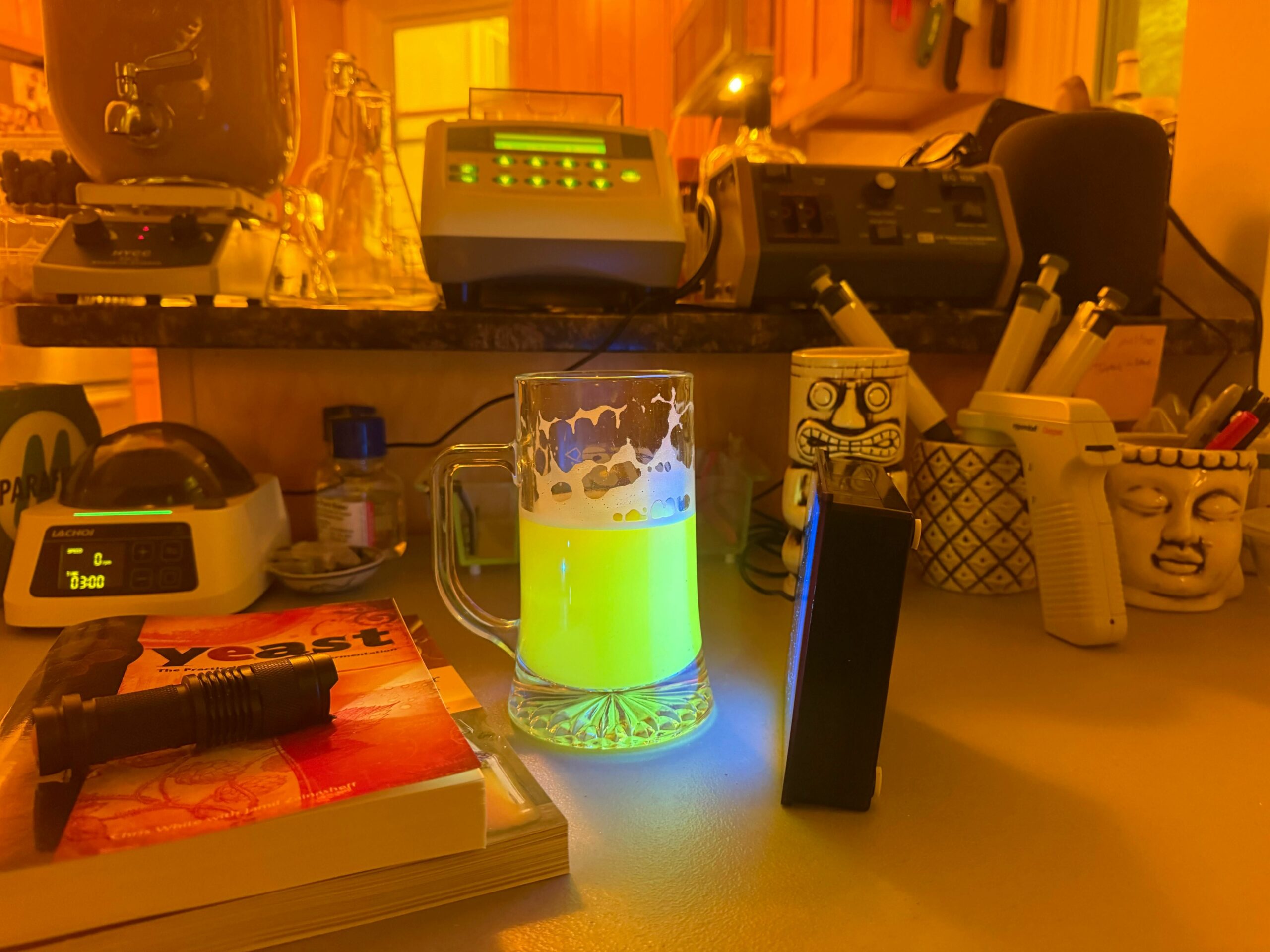

The beer is a Lithuanian-style farmhouse ale

Nor does a vaccine have to be delivered in a beer. Buck, 55, thinks the modified yeast could be used to make yoghurt, or crisps, that could confer a similar immunity.

The scientist does not usually whip up experiments in his kitchen, and some of his peers are now alarmed that his homebrew adventures could damage public trust in vaccines. They also warn that one beer drinker conducting tests on himself does not establish the efficacy of a supposed treatment.

“I disagree,” said Buck, who has been a scientist at the National Institutes of Health since 2001. “I think if a food vaccine works in one person that tells you something very important, which is that it can work in at least one person.”

Vaccines are often made inside insect cells, but they can also be created in yeast cells: there is then a tricky “purification” process, stripping everything else away to leave a protein particle for injection. “It eventually just occurred to me, like maybe we don’t have to purify,” he said. Perhaps the yeast could simply be eaten, or drunk in a foaming pint.

The conventional wisdom is that this does not work because vaccine proteins are broken down by stomach acid, he said. This proved true when Buck and his colleagues fed mice with ground-up yeast containing vaccine proteins, supplied by a Lithuanian scientist named Alma Gedvilaite. But when they tried whole, live yeast containing the virus particles, the mice developed “robust antibody responses”.

“I literally felt weak at the knees,” Buck said. “I could see that this meant that the vaccine could be a food. And if it can be a food, it means you can regulate it like a food and it’s easy to distribute and many people will be happier about it than a shot. All of these implications were there at that first experiment a year and a half ago.”

Buck initially started working on potential vaccines for HIV, HPV and polyomaviruses. “Their name is ancient Greek for ‘many tumours’,” he said of the latter. “It causes cancer in mice for sure.” They can also cause serious problems for transplant patients taking immunosuppresant drugs. Buck’s laboratory at the National Cancer Institute is working with the biotech company Biological E on a vaccine for polyomaviruses that would be administered by injection, but they are still some distance from clinical trials.

• US measles cases surpass 2,000 for first time in 30 years

A food-based, or beer-based vaccine, available at once, could potentially save lives, he said. “Anyone who is waiting for a transplant would like this vaccine,” he said. “If I were waiting for a transplant I would get it immediately.”

Besides being suspected of causing cancer, the polyomavirus can cause a painful bladder condition in patients who receive bone-marrow transplants. Buck recalls visiting a paediatric hospital that had installed sound-proofing in its lavatories to dampen the sounds of children with the condition screaming in the middle of the night. It may also cause a painful bladder condition in older women, he said. Patients with it “shed a lot of polyomavirus in their urine”, he said. “That’s not causality … but [if] you have painful bladder syndrome, you brew beer, you drink beer, and if the pain goes away, then you say ‘Yahtzee’.”

He said he tried to put the beer idea before an institutional review board at the National Institutes of Health. “A senior official in the chain bounced away the application before it could be considered,” he said. “The friction was that the institution is not accustomed to thinking about food.”

He thinks they were trying to assess it the way they would a drug.

Buck didn’t have much patience for that red tape. “Instead of trying to convince them what the law was, I basically demonstrated what the law was by doing it in my kitchen,” he said. He got his younger brother Andrew to form a company, and sell batches of the beer to two close friends. “We just need a company with a record of sales,” said Buck, who lives in Bethesda, Maryland. “If something is already in the food supply and doesn’t appear to be causing problems, then the manufacturer can just say, look, it’s generally recognised as safe because it’s already there and we don’t know of any problems.”

Over the summer, after drinking his own beer but before tests showed he had developed antibodies, Buck spoke at a virology conference in southern Italy. Michael Imperiale, a virologist and emeritus professor at the University of Michigan Medical School, watched his presentation.

“I said: ‘What are you going to do if someone has a bad reaction to this?’” Imperiale said. He felt that one man and his brother drinking a beer vaccine was not enough to show that something was safe. He said that trials on, say, a thousand people with diverse genetics would be required. But his main concern was that with Robert F Kennedy Jr, a famous vaccine sceptic who as US health secretary has diminished trust in vaccines, it could make matters worse to have a government scientist brewing them in his kitchen.

“The US government itself is trying to actively get people to be against vaccines, right?” Imperiale said. “We, the scientific community, really have to keep that in mind … Is what we’re doing going to enhance the public trust or is it going to make it worse?”

The beer becomes fluorescent under blue light

Several other scientists have told Science News, which first reported on Buck’s vaccine beer, that they have similar concerns.

But Buck says his own mother is an antivaxer. “She lives in eastern Washington state, which is a very rural environment. All of her church friends are antivaxers,” he said. “I used to agree with the view that the solution to distrust of vaccines was to raise our safety standards and have more and more stringent qualifications for vaccines that hit the market. And with hindsight, I think it backfired.”

He thinks scientists’ efforts to show that they take elaborate care with a vaccine — Buck refers to it as “security theatre” — only made people think: “Wow, that thing must be really dangerous.” But producing a vaccine that people can make in their own kitchen proves a vaccine “is just some ordinary thing that is not that dangerous”, he said.

On December 17, Buck and his brother published a non-peer-reviewed paper, Vaccine Beer: A Personal Healthcare Report, which contained recipes for vaccine beer. In the coming months, he hopes to persuade a company to manufacture the modified yeast and to find a brewer willing to make a line of what he calls VAC-beer (Vaccine Antigen Containing) for sale in North America. (He doubts it could be sold in Britain or Europe, given the regulations on genetically modified foodstuffs.)

“I don’t know what Robert Kennedy is going to make of this,” he said. “This is my boss’s boss’s boss and I do not know whether he will think: ‘Oh, it looks like health food, I love it!’ Or: ‘Oh, it looks like a vaccine, I hate it.’ I have no idea how that’s going to come out.”

• Vaccine sceptic, conspiracist, ‘liar’: it’s Robert F Kennedy Jr

What about his mother?

“Mom seems entirely amenable to beer vaccine,” he said. “But I wouldn’t call it an informative datapoint because my love for food and home fermentation projects was inherited directly from her. The more interesting datapoints are Mom’s church friends.”

He added: “In a couple cases, I intuited some level of quiet glee about the idea of having an excuse to drink beer.”