This post was originally published on here

A team of scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology has sequenced the second high-quality Denisovan genome, extracted from a molar discovered in Denisova Cave, Siberia. This new genome, dated to around 200,000 years ago, predates all previously sequenced Denisovan individuals and is reshaping theories on early human migrations, interbreeding, and geographic range. A preprint of the study was published on bioRxiv.org on October 20, 2025.

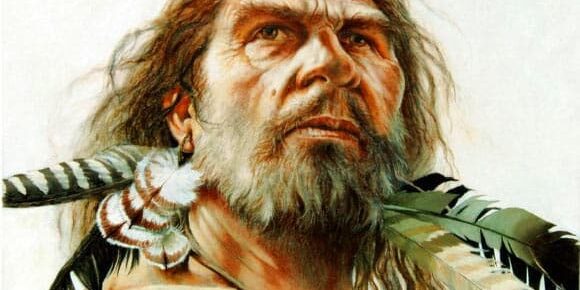

A New Window Into Denisovan Origins

The sequencing of this ancient genome marks a major breakthrough in human evolutionary research. While Denisovans were first identified in 2010 from DNA in a finger bone, our understanding of them has remained fragmented due to the scarcity of well-preserved specimens. “Denisovans, an extinct human group, were first identified based on ancient DNA extracted from Denisova 3, a finger phalanx discovered at Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia in 2008,” Dr. Stéphane Peyrégne and co-authors noted. That sample, Denisova 3, was, until now, the only one yielding a genome of usable quality.

“Analysis of the nuclear genome from this individual revealed that Denisovans were a sister group to Neanderthals, another group of now extinct humans who lived in Western Eurasia in the middle and late Pleistocene.” This link with Neanderthals was foundational for understanding Denisovan ancestry and interactions. Still, the timeline of their divergence and their full geographic spread remained obscure.

The new specimen, Denisova 25, significantly alters the timeline. Recovered from one of the lowest layers in the cave’s South Chamber, the molar dates back to between 200,000 and 170,000 years ago, according to optically stimulated luminescence. “In 2020, a complete left upper molar was found in layer 17, one of the lowest cultural layers of the South Chamber of Denisova Cave, dated to 200,000-170,000 years ago by optically stimulated luminescence,” the scientists explained. This makes Denisova 25 the oldest sequenced Denisovan to date, twice as ancient as Denisova 3.

The Tooth That Changed Human History

Designated as Denisova 25, this molar isn’t just ancient, it’s remarkably well-preserved. Its size and structure were key clues in identifying it as Denisovan.

“Designated as Denisova 25, this molar is similar in size to the other molars discovered at Denisova Cave, Denisova 4 and Denisova 8, and larger than those of Neanderthals as well as most other Middle Pleistocene and later hominins, suggesting that it potentially belonged to a Denisovan.”

Obtaining the genome was a delicate process. “Two samples of 2.7 and 8.9 mg were removed by drilling one hole at the cemento-enamel junction of the tooth, and twelve subsamples, ranging from 4.5 to 20.2 mg, were obtained by gently scratching the outer layer of one of the roots with a dentistry drill.” Thanks to the excellent DNA preservation, researchers reconstructed a high-coverage genome, comparable in quality to Denisova 3.

This second complete genome unlocks the possibility of comparing Denisovan populations over time. The researchers discovered that the two Denisovans, Denisova 3 and Denisova 25, belonged to genetically distinct groups, indicating that the Altai Mountains were home to multiple waves of Denisovan occupation. The older Denisovan even had a greater proportion of Neanderthal DNA, highlighting a long history of interbreeding.

Evidence Of Complex Interbreeding And Migration

The findings further suggest a complex web of human migration and interaction in Ice Age Eurasia. “Using this second Denisovan genome has shown that there was recurrent mixing between Neanderthals and Denisovans in the Altai region, but that these mixed populations were replaced by Denisovans from elsewhere, supporting the idea that Denisovans were widespread and that the Altai may have been at the edge of their geographic range,” the researchers said.

This paints a dynamic picture of ancient hominin movement, contradicting previous notions of isolated populations. The team also found signs of admixture with an even older, “super-archaic” hominin group, predating the divergence of modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans.

The new genome also helps explain the patchwork pattern of Denisovan ancestry in present-day populations. People in Oceania, South Asia, and East Asia all carry different variants of Denisovan DNA. Some populations appear to have inherited Denisovan genes from multiple lineages, implying separate migration events into Asia. These independent gene flows challenge the idea of a single, linear migration path.

A preprint of the study, titled “A high-coverage genome from a 200,000-year-old Denisovan”, was posted on bioRxiv.org and is now fueling debate across the paleoanthropology community.

Traces In Our Blood: What Denisovans Left Behind

The research also uncovered dozens of genetic regions in modern humans that appear to have been shaped by Denisovan DNA. Many of these genes are tied to important traits such as height, blood pressure, and immune system function. The study identified 16 gene associations with 11 Denisovan alleles, potentially affecting modern-day phenotypes including cholesterol levels, monocyte count, hemoglobin concentration, and even C-reactive protein levels, key markers in inflammation and immunity.

The impact goes beyond biology. Some of the Denisovan-specific mutations are located near genes tied to cranial shape, jaw projection, and possibly even speech and cognition. One particularly intriguing variant was found close to FOXP2, a gene associated with language acquisition in modern humans. While the researchers caution against overinterpretation, these genomic clues offer a rare glimpse into what Denisovans might have looked and sounded like, insights not possible from bones alone.

“While twelve fragmentary remains and one cranium have since been attributed to Denisovans based on DNA or protein analysis, only Denisova 3 has yielded a high-quality genome.” This second genome now offers a much-needed comparative reference, opening new paths for understanding Denisovan adaptation, evolution, and their lasting legacy in our own species.