This post was originally published on here

Finding an ordinary planet to study turns out to be quite an extraordinary endeavor. The most common size for planets in our universe is larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. Frustratingly, there are exactly zero planets that fit the bill in our solar system, forcing scientists to search the cosmos to study how they’re formed. But with a lot of effort and a stroke of luck, an international team of astrophysicists from the University of California, Los Angeles just found some prime candidates orbiting the star V1298 Tau, publishing their findings today in Nature.

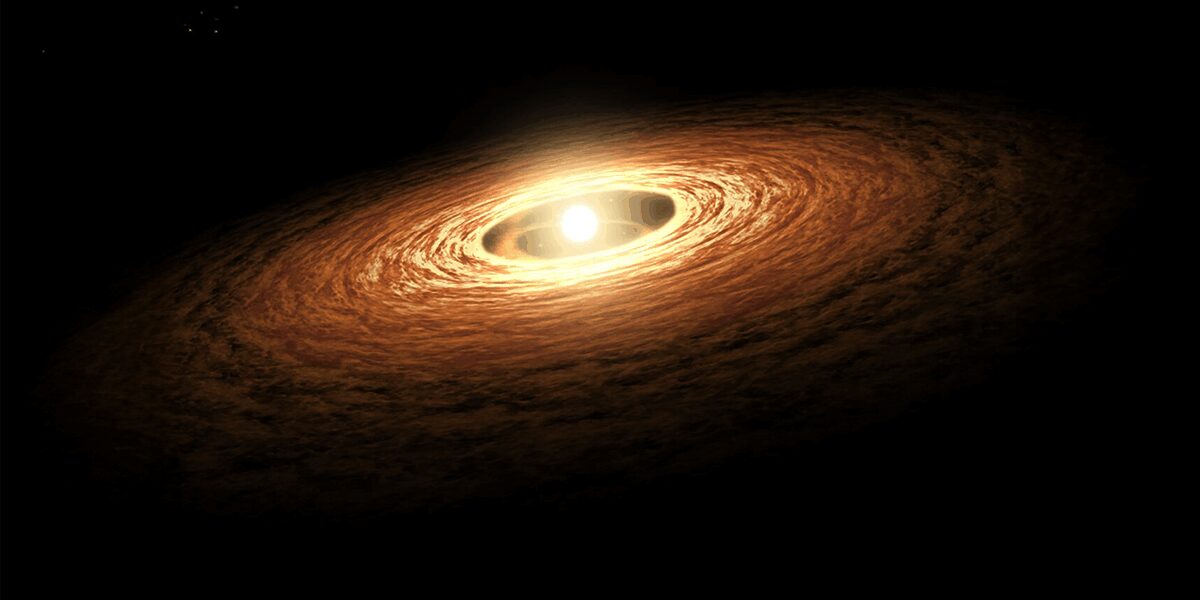

“I’m reminded of the famous ‘Lucy’ fossil, one of our hominid ancestors that lived 3 million years ago and was one of the ‘missing links’ between apes and humans,” study co-author Erik Petigura of UCLA explained in a statement. “V1298 Tau is a critical link between the star- and planet-forming nebulae we see all over the sky, and the mature planetary systems that we have now discovered by the thousands.”

Compared to our 4.5-billion-year-old sun, the 20-million-year-old V1298 Tau is a stellar baby, making it ideal for exploring planet formation. For almost a decade, astronomers kept tabs on the star system, waiting for planets to transit in front of the star.

Read more: “Looking for a Second Earth in the Shadows”

“We had two transits for the outermost planet separated by several years, and we knew that we had missed many in between,” Petigura added. “There were hundreds of possibilities which we whittled down by running computer models and making educated guesses.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Recording these transits provided researchers with information to pin down their orbital trajectories and timings, which then allowed them to decipher clues about the planets’ physical characteristics. After crunching the numbers, the astronomers made a surprising discovery: Despite these planets having volumes hundreds of times larger than Earth’s—ranging in size from Neptune-like to Jupiter-like—their masses were only five to 15 times larger.

Put simply, they had the density of styrofoam.

“The unusually large radii of young planets led to the hypothesis that they have very low densities, but this had never been measured,” said study co-author Trevor David of the Flatiron Institute in New York City. “By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof. They are indeed exceptionally ‘puffy,’ which gives us a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution.”

So how will these giant baby planets become the Goldilocks-sized planets most common in the universe? Astronomers determined that rather than growing larger, they’re rapidly losing their atmospheres.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“The four planets we studied will likely contract into ‘super-Earths’ and ‘sub-Neptunes’—the most common types of planets in our galaxy,” study co-author John Livingston said, “but we’ve never had such a clear picture of them in their formative years.”

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

This story was originally featured on Nautilus.