This post was originally published on here

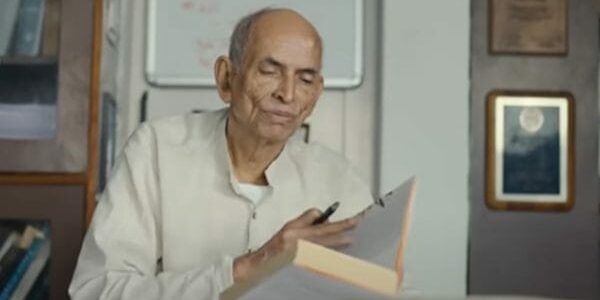

New Delhi: Madhav Gadgil decided to become a field ecologist at the age of 14 after receiving a letter from India’s famous birder, Salim Ali.

Growing up in Pune in the early 1950s, Gagdil would accompany his father on nature walks and bird watching expeditions near their house, and when a striking feature of a green bee-eater bird confused him, he decided to write to Ali himself, whose books he had read earlier.

“I was captivated by his knowledge, wit and charm – at the age of fourteen, I decided to become a field ecologist just like him,” Gadgil wrote in his 2023 memoir, A Walk Up the Hill.

For the next 70 years of his life, Gadgil did exactly that, becoming India’s foremost ecologist and educator, and the father of the landmark ‘Gadgil Report’ officially known as the ‘Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP)’ in 2010, calling for the protection of the Western Ghats as ecologically sensitive areas. He also founded the Centre for Ecological Sciences in 1983 at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore (IISc), working closely with policymakers, forest communities, and activists.

He passed away aged 83 in his Pune home late at night on 7 January after a brief illness, leaving a legacy of ecological conservation and scholarship. Gadgil is survived by his son, daughter, and grandchildren. His wife, Sulochana Gadgil, passed away in 2025. His students include historian and environmentalist Ramachandra Guha, who also collaborated with Gadgil on three books on the Indian environment and ecology.

Jairam Ramesh, Congress politician and former Union Minister of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, in a post on X said, “He was a top-notch academic scientist, a tireless field researcher, a pioneering institution-builder, a great communicator.”

Ramesh ended by saying, “Nation builders come in different forms and varieties. Madhav Gadgil was definitely one of them.”

Also Read: ‘Centre should refer to 2013 report’ — ex-ISRO chief on upcoming Western Ghats notification

Early work and research

Educated in Pune’s Fergusson College, Mumbai University, and Harvard University, Gadgil’s pedagogy was largely in the field of zoology and botany. He returned to India in 1971 with his wife, Sulochana Gadgil, a scientist and meteorologist, as both wanted to contribute to the scientific community in their own country.

It was through Sulochana that Gadgil received his job offer from the IISc in 1973. When the director Satish Dhawan wrote to Sulochana Gadgil inviting her to join their institute, she promptly asked him whether they would be willing to hire her husband, a PhD in mathematical ecology, along with her. Thus began the Gadgils’ tryst with IISc, and it was here that Gadgil established himself for the next three decades as a professor and later the founder of the new centre.

Even as a professor and researcher, Gadgil’s major fascination was towards the Western Ghats throughout his life. In his memoir, he mentioned how his family hailed from North Goa, and he grew up in Pune, travelling across Maharashtra and Karnataka with his father.

“I grew up to be rather different from the usual brand of urban nature lovers, who viewed rural people, their farms and livestock as the principal enemies of India’s nature,” he recalled in the book. “I admired the buffaloes as much as the gaurs, and was as at home with the farmers as with the scholars.”

From the sacred groves in Maharashtra’s Aamby Valley to the elephants in Karnataka’s Bandipur National Park, to identifying biosphere reserve sites in the Niligiris, Gadgil’s early research in India spanned the extent of the Western Ghats and often manifested into policy outcomes too. He was responsible for the creation of India’s first-ever biosphere reserve — the Nilgiris Biosphere Reserve in 1986.

Gadgil was also an environmental rights activist, taking part in the Silent Valley protests of the 1970s, the Chipko Movement of 1973, including field visits to Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Chhattisgarh to meet forest communities struggling to balance protection alongside sustainable use of forest resources.

Over the years, he published over 200 scientific papers and reports documenting the fissures in Indian ecological development and policies, and was first made a member of the Scientific Advisory Council to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1986, a post he held till 1990. He was also instrumental in advocating for the People’s Biodiversity Register under India’s Biological Diversity Act of 2002, bringing in local knowledge of biodiversity into the governance sphere.

Also Read: Karnataka is ignoring Western Ghats UNESCO tag and 6 central notices—to build, build, build

Western Ghats Expert Panel

In 2010, then environment minister Jairam Ramesh set up the WGEEP to assess the ecological status of the area, and make recommendations for the conservation and protection of the Ghats by involving both the people and the government. Gadgil was asked to chair the panel.

With close to three decades of experience walking across the Ghats and meeting the locals, participating in their struggles for protection and rights to protect their land, Gadgil was prepared for the endeavour. Through his efforts emerged a momentous document that called for 75 per cent of the 1,60,000 sq km of the Western Ghats to be protected as an ecologically sensitive zone.

From banning mining to promoting the implementation of the Forest Rights Act to no large storage dams or polluting industries, the panel recommended various strategies for the conservation of the Ghats as a region of “unique biological heritage”. The report was completed in 2011 and made public in 2012.

Despite being the kick-off point for several government and civil society arguments towards greater protection of the Western Ghats, the WGEEP report was never fully implemented by the Centre. Multiple attempts by Gadgil and other members of the committee to urge the government to consider their recommendations and protect the Western Ghats from rampant mining and destruction failed. Since 2014, the Union environment ministry issued six draft notifications to demarcate 56,000 sq km of the Western Ghats as ecologically sensitive; the final notification is still pending.

Even after the devastating landslides in Wayanad in Kerala in 2024, Gadgil gave press interviews; stressing the need to revert to his 2010 report for urgent protection of the Ghats.

He continued his work in ecological conservation, winning laurels like the Padma Bhushan in 2006, the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement in 2014, and the United Nations Champion of the Earth award in 2024. Gadgil believed in the rights of local communities and in inclusive development.

“I am both a realist and an incorrigible optimist, and believe that the knowledge revolution which science has ushered in holds signs of hope,” wrote Gadgil in the final chapters of his memoir.

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)