This post was originally published on here

Liquids and solutions may look simple, but on the molecular scale they are constantly shifting and reorganizing. When sugar dissolves in water, each sugar molecule quickly becomes surrounded by fast moving water molecules. Inside living cells, the situation is even more intricate. Tiny liquid droplets transport proteins or RNA and help coordinate many of the cell’s chemical activities.

Even though liquids play a central role in chemistry and biology, they are extremely difficult to study at the level of individual molecules and electrons. Unlike solids, liquids do not have a fixed structure. The fastest interactions between dissolved molecules and their surroundings are also the most important, yet these ultrafast events have remained largely out of view.

A New Technique for Seeing Ultrafast Electron Motion

Researchers from Ohio State University and Louisiana State University have now demonstrated that high-harmonic spectroscopy (HHS) can be used to uncover subtle structures inside liquids. This nonlinear optical method can track electron motion on attosecond timescales. The study, published in PNAS, represents a major step toward directly observing how solutes and solvents interact in liquid solutions.

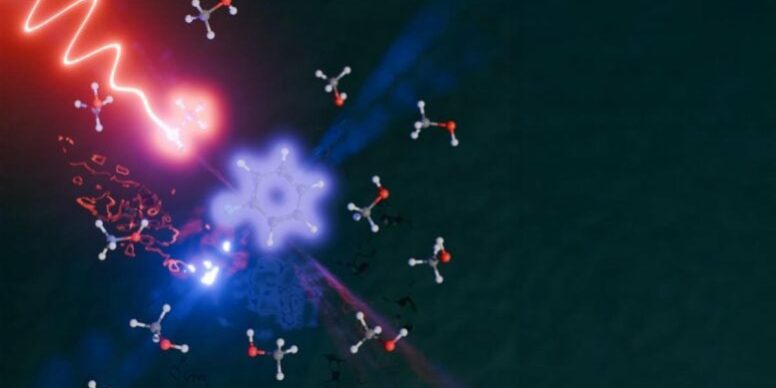

HHS relies on extremely short laser pulses that momentarily pull electrons away from their molecules. When the electrons return, they emit light that reveals how electrons and even atomic nuclei move. These snapshots occur on timescales far beyond the reach of conventional tools. Traditional optical spectroscopy has long been used to study liquids because it is gentle and easy to interpret, but it operates much more slowly. HHS, in contrast, extends into the extreme ultraviolet and can resolve events lasting just an attosecond, which is a billionth of a billionth of a second.

Making High-Harmonic Spectroscopy Work in Liquids

Until recently, HHS experiments were mostly limited to gases and solids, where conditions are easier to control. Liquids present two major obstacles. They absorb much of the harmonic light that is produced, and their constantly moving molecules complicate the signal.

To overcome these problems, the OSU and LSU team created an ultrathin liquid “sheet” that allows more light to escape. Using this approach, they showed for the first time that HHS can detect rapid molecular motion and local structural changes in liquids.

Testing Simple Liquid Mixtures

With this new setup in place, the researchers examined a series of simple liquid mixtures. They directed intense mid infrared laser light at methanol mixed with small amounts of halobenzenes. These molecules are nearly identical and differ only by a single atom: fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine. Halobenzenes generate strong harmonic signals that are easy to identify, while methanol provides a clean background. The team expected the halobenzene signal to dominate even when present in very small amounts.

For most mixtures, that expectation was correct. The emitted light looked like a straightforward combination of the two liquids. Fluorobenzene (PhF), however, stood out. “We were really surprised to see that the PhF–methanol solution gave completely different results from the other solutions,” said Lou DiMauro, Edward E. and Sylvia Hagenlocker Professor of Physics at OSU. “Not only was the mixture-yield much lower than for each liquid on its own, we also found that one harmonic was completely suppressed.” He added that “such a deep suppression was a clear sign of destructive interference, and it had to be caused by something near the emitters.”

In practical terms, the PhF and methanol mixture produced less light than either liquid alone, and one specific harmonic disappeared entirely. It was as if a single “note” in the spectrum had been silenced. This kind of selective loss is extremely rare and pointed to a specific molecular interaction that was disrupting the electrons’ motion.

Simulations Point to a Molecular Handshake

To investigate further, the OSU theory team ran large scale molecular dynamics simulations. John Herbert, professor of chemistry and leader of the theory effort, explained: “We found that the PhF–methanol mixture is subtly different from the others. The electronegativity of the F atom promotes a ‘molecular handshake’ (or hydrogen bond) with the O–H end of methanol, whereas in other mixtures the distribution of the PhX molecules is more random.” In short, fluorobenzene forms a more organized solvation structure than the other halobenzenes.

The LSU theory group then tested whether this structure could explain the experimental findings. Mette Gaarde, Boyd Professor of Physics, said: “We speculated that the electron density around the F atoms was providing an extra barrier for the accelerating electrons to scatter on, and that this would disturb the harmonic generation process.” Using a model based on the time dependent Schrödinger equation, the team confirmed that such a scattering barrier could account for both the missing harmonic and the reduced overall signal. “We also learned that the suppression was very sensitive to the location of the barrier—this means that the detail of the harmonic suppression carries information about the local structure that was formed during the solvation process,” added Sucharita Giri, postdoctoral researcher at LSU.

“We were excited to be able to combine results from experiment and theory, across physics, chemistry, and optics, to learn something new about electron dynamics in the complex liquid environment.”

Mette Gaarde, LSU Boyd Professor of Physics

Why These Findings Matter

Although more research is needed to fully explore what HHS can reveal in liquids, the early results are encouraging. Many essential chemical and biological processes take place in liquid environments. The energies of the electrons involved are also similar to those responsible for radiation damage. A better understanding of how electrons scatter in dense liquids could therefore have far reaching effects across chemistry, biology, and materials science.

As DiMauro noted, “Our results demonstrate that solution-phase high-harmonic generation can be sensitive to the particular solute–solvent interactions and therefore to the local liquid environment. We are excited for the future of this field.” Researchers expect that continued improvements in experiments and simulations will renew interest in ultrafast studies of liquids and allow scientists to extract detailed structural and dynamic information about how liquids respond to ultrafast laser pulses.

Reference: “Solvation-induced local structure in liquids probed by high-harmonic spectroscopy” by Eric Moore, Sucharita Giri, Andreas Koutsogiannis, Tahereh Alavi, Greg McCracken, Kenneth Lopata, John M. Herbert, Mette B. Gaarde and Louis F. DiMauro, 25 November 2025, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2514825122

Key contributors to this work include Eric Moore, Andreas Koutsogiannis, Tahereh Alavi, and Greg McCracken from OSU; and Kenneth Lopata from LSU. This study was funded by the DOE Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, and by the National Science Foundation.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.