This post was originally published on here

Wyoming’s “Mummy Zone” has long been known for its exceptional preservation of dinosaur fossils, but a new study published in Science offers unprecedented insight into how these ancient creatures looked in life. The study focuses on the remarkably well-preserved remains of Edmontosaurus annectens, a duck-billed dinosaur, revealing intricate details of its skin and other soft tissues, preserved as 66-million-year-old mummies.

A Snapshot of Life 66 Million Years Ago: The Mummy Zone’s Remarkable Preservation

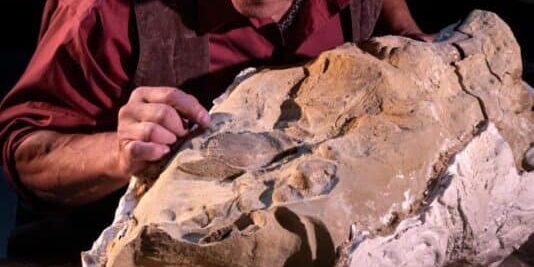

The Wyoming “Mummy Zone” has become a paleontological treasure trove, offering fossil discoveries that push the boundaries of what we know about dinosaurs. The preservation of fossils, especially soft tissues like skin and crests, is an extraordinary occurrence in paleontology, where fossils are usually just bones. These “mummies” are not like the ancient remains from Egyptian tombs, rather, they are the skeletons of dinosaurs encased in a thin layer of clay, preserving impressions of their flesh in 3D. This unusual preservation mechanism, called “clay templating,” occurs when the body is quickly buried by floodwaters, trapping fine details of the animal’s surface in a mold of clay no thicker than a few millimeters.

As Paul Sereno, a senior author of the study published in Science, and professor of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago, explains, this technique allows scientists to observe details previously unimaginable.

“We’ve never been able to look at the appearance of a large prehistoric reptile like this,” Sereno said. “It’s the first time we’ve had a complete, fleshed-out view of a large dinosaur that we can feel really confident about.”

This insight allows scientists to get a glimpse of what these dinosaurs looked like in life, providing details on their skin texture, body proportions, and features that had previously been unknown.

How The Mummies Were Preserved: The Role of Wyoming’s Unique Environment

The area’s unique environmental conditions, with seasonal monsoons and floods, played a crucial role in the preservation of these ancient creatures. In particular, the rapid burial of the dinosaurs, likely caused by fast-moving floodwaters, allowed for their preservation in such fine detail. During this time, Wyoming’s Badlands were subjected to periodic floods and droughts, which would have created ideal conditions for the quick entombment of these dinosaurs in sediment layers. The presence of broken bones, tree debris, and mixed gravel within the sediment suggests that the floodwaters were violent and swift, entombing the animals shortly after they died.

Sereno describes the Badlands of Wyoming as an extraordinary site for paleontological discovery: “The Badlands in Wyoming where the finds were made is a unique ‘mummy zone’ that has more surprises in store from fossils collected over years of visits by teams of university undergrads.” This region continues to be a hotbed of dinosaur discovery, with researchers eagerly anticipating the potential for even more surprises as they explore this prehistoric graveyard.