This post was originally published on here

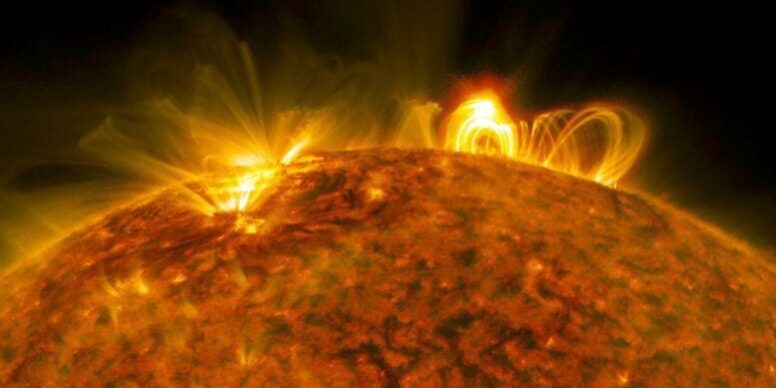

Researchers have identified a newly recognized type of extremely energetic particles located in the Sun’s upper atmosphere, revealing a phenomenon that had not been detected before.

Solar scientists report that they have identified an important source of the powerful gamma rays released during the Sun’s most extreme eruptions.

According to research published in Nature Astronomy, a team from NJIT’s Center for Solar-Terrestrial Research (NJIT-CSTR) has identified a previously unrecognized group of high-energy particles in the Sun’s upper atmosphere. These particles appear to be responsible for mysterious radiation signatures that scientists have observed during major solar flares for many years.

The researchers traced the signals to a small, concentrated area of the solar corona during an intense X8.2-class flare on September 10, 2017. In that region, they detected enormous numbers of particles reaching energies of several million electron volts (MeV), far exceeding the energy levels typically associated with solar flares and traveling at speeds close to that of light.

Scientists think these particles produce gamma rays through a process known as bremsstrahlung. In this process, lightweight charged particles such as electrons release high-energy radiation when they collide with matter in the Sun’s atmosphere.

The research team says this finding helps resolve long-standing questions about how solar flares generate extreme radiation. It may also lead to better models of solar behavior, which could ultimately improve predictions of space weather.

“We knew solar flares produced a unique gamma-ray signal, but that data alone couldn’t reveal its source or how it was generated,” said Gregory Fleishman, NJIT-CSTR research professor of physics and lead author of the study. “Without that crucial information, we couldn’t fully understand the particles responsible or evaluate any potential impact on our space weather environment. By combining gamma-ray and microwave observations from a solar flare, we were finally able to solve this puzzle.”

Combining Space and Ground-Based Observations

To pinpoint the source of the radiation, the NJIT researchers brought together observations of the 2017 flare from two complementary instruments. These included NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and NJIT’s Expanded Owens Valley Solar Array (EOVSA), an advanced radio telescope system located in California.

The Fermi telescope recorded detailed measurements of high-energy gamma rays emitted during the flare. At the same time, EOVSA provided microwave images that revealed where energetic particles were moving within the solar corona.

When the team analyzed the two datasets together, they identified a specific area in the solar atmosphere known as Region of Interest 3 (ROI 3). This region stood out alongside two previously examined areas, ROI 1 and ROI 2, because it showed overlapping microwave and gamma-ray signals, pointing to the presence of an unusual population of highly energized particles.

This convergence pointed to a unique population of particles energized to MeV levels.

“Unlike the typical electrons accelerated in solar flares, which usually decrease in number as their energy increases, this newly discovered population is unusual because most of these particles have very high energies, on the order of millions of electron volts, with relatively few lower-energy electrons present,” explained Fleishman.

Using advanced modeling, the team linked the energy distribution of these particles directly to the observed gamma-ray spectrum, pointing to bremsstrahlung emission — high-energy light usually produced when electrons collide with solar plasma — as the elusive source of the gamma-ray signals.

Implications for Solar Flare Physics

Fleishman also says their observations within ROI 3 — located near regions of significant magnetic field decay and intense particle acceleration — support long-standing theories about how solar flares accelerate particles to extreme energies and sustain them.

“We see clear evidence that solar flares can efficiently accelerate charged particles to very high energies by releasing stored magnetic energy. These accelerated particles then evolve into the MeV-peaked population we discovered,” said Fleishman.

For now, Fleishman says key questions remain about these extreme particle populations.

Future observational insights could soon come from NJIT’s Expanded Owens Valley Solar Array (EOVSA), currently being upgraded to EOVSA-15. This project, led by NJIT-CSTR professor of physics and EOVSA director Bin Chen — a co-author on the study — is funded by the National Science Foundation and will enhance the array with 15 new antennas and advanced ultra-wideband feeds.

“One big unknown is whether these particles are electrons or positrons,” Fleishman said. “Measuring the polarization of microwave emissions from similar events could provide a definitive way to tell them apart. We expect to gain this capability soon with the EOVSA-15 upgrade.”

Reference: “Megaelectronvolt-peaked electrons in a coronal source of a solar flare” by Gregory D. Fleishman, Ivan Oparin, Gelu M. Nita, Bin Chen, Sijie Yu and Dale E. Gary, 7 January 2026, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02754-w

The team’s study was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.