This post was originally published on here

In a forested valley of southern France, the largest international energy project ever undertaken is quietly entering a critical new stage. After decades of design, diplomacy, and precision manufacturing, construction teams are now attempting something no one has done before: assemble a machine capable of replicating the nuclear reactions that power the stars.

It is not a prototype for a power plant. It will not produce electricity. Yet the stakes are unusually high. If successful, this machine could demonstrate that nuclear fusion, long confined to laboratories and theory, can be achieved at industrial scale.

The project, known as ITER, has operated under intense global scrutiny since its inception. Funded and managed by 35 countries, including the United States, China, the European Union, and Russia, it represents a collective investment in a possible future energy system that is abundant, safe, and carbon-free.

That promise, however, rests on whether the device can perform under extreme physical conditions. And whether its multinational structure, which spans continents and political systems, can deliver the precision and reliability the project now demands.

Reactor Assembly Enters Most Technically Sensitive Phase

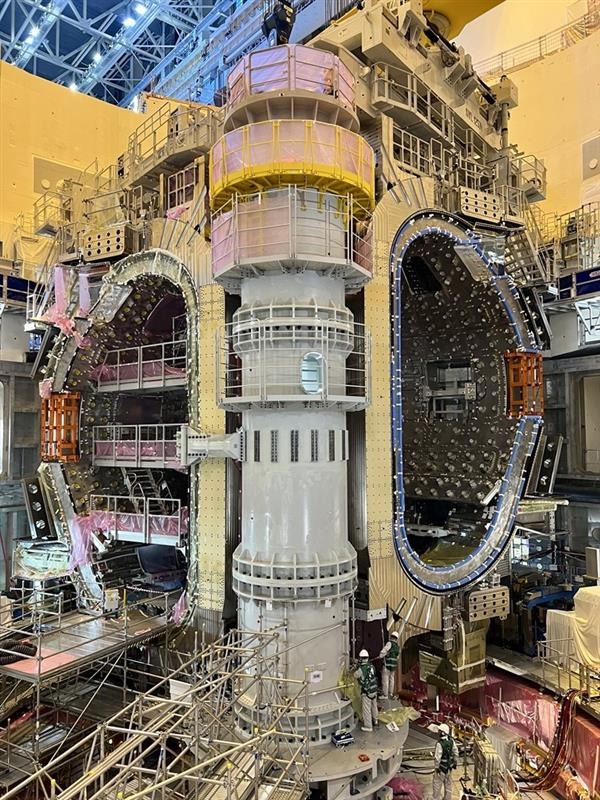

At the centre of the ITER facility in Saint-Paul-lez-Durance, engineers have begun lowering massive steel components into the reactor’s core. These vacuum vessel sectors, each weighing over 400 tonnes, form the toroidal chamber where fusion is meant to occur. Alignment tolerances are within a few millimetres. Deviations could compromise the reactor’s ability to sustain plasma.

The design of the reactor is based on the tokamak concept, a magnetic confinement system first developed by Soviet physicists in the 1960s. The ITER tokamak, once complete, will be the largest in the world. Its chamber is designed to contain superheated plasma reaching temperatures of 150 million degrees Celsius, more than ten times the core temperature of the Sun.

Once hydrogen nuclei are heated and pressurised into plasma, magnetic coils will confine them in a stable loop, allowing them to fuse into helium. The process releases energy, which could be harnessed in future reactors to generate electricity. The goal for ITER is to produce 500 megawatts of thermal energy from 50 megawatts of input power, a ratio of Q = 10. No fusion experiment has yet achieved that level of energy return.

The assembly is led by Westinghouse, in coordination with European contractors Ansaldo Nucleare and Walter Tosto. The challenge is not only technical but logistical. Each vacuum vessel sector must integrate seamlessly with components sourced across multiple continents, some built years apart under different regulatory frameworks.

Delays and Revised Targets in New Baseline Strategy

In July 2024, ITER leadership released an updated Baseline Plan that shifted its schedule and design strategy. According to the plan, operations using deuterium-deuterium plasma will begin in 2035, with full magnetic testing expected the following year. The project’s most ambitious goal, initiating deuterium-tritium fusion, is now set for 2039.

The revision reflects both engineering challenges and a change in risk management. One significant modification involves replacing the original beryllium first wall material with tungsten, which has higher heat resistance and better long-term performance under neutron bombardment.

The earlier timeline had aimed for “first plasma” by 2018. In reality, manufacturing delays, integration issues, and supply chain coordination across 35 nations pushed that milestone back by nearly two decades. Project officials now prioritise durability and repeatability over speed, according to the Baseline Plan presented last year.

Though ITER will not generate electricity, its success is intended to validate the technologies and systems that would underpin DEMO, a proposed commercial demonstration plant in development in Europe and Asia.

Components, Scale, and International Coordination

More than 100,000 kilometres of superconducting wire have been manufactured for ITER’s magnet system, requiring a tenfold increase in global production capacity over pre-project levels. These figures, and other technical benchmarks, are detailed on ITER’s Facts and Figures page. The wire, made from niobium-tin, forms the basis for the toroidal field coils that will contain the plasma. Each coil is 17 metres high, 9 metres wide, and weighs over 300 tonnes.

The reactor also includes a central solenoid, a massive electromagnet that must contain forces equivalent to twice the thrust of a space shuttle launch. Its task is to drive plasma current and maintain the internal magnetic field. These components are supported by a bespoke infrastructure platform spanning 42 hectares, with construction oversight involving more than 5,000 on-site workers as of 2025.

Shipping the components to the inland site required the construction of the ITER Itinerary, a 104-kilometre modified road network capable of accommodating loads up to 900 tonnes. Each component is transported via radio-controlled platforms at night to minimise disruption.

The logistical complexity of integrating contributions from 35 countries remains one of ITER’s defining features. The European Union is responsible for nearly half of the construction cost and five of the nine vacuum vessel sectors. South Korea provides the remaining four. The United States, Japan, Russia, China, and India supply other major subsystems, including magnet components, support structures, and heating systems.