This post was originally published on here

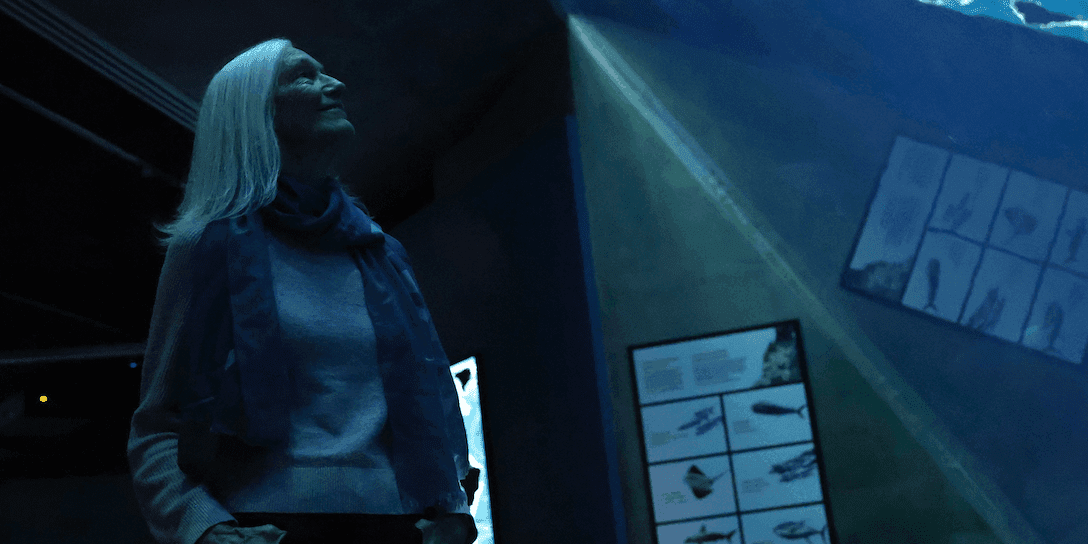

How—and where—do we decide to give our attention? Katie Rodriguez here, processing the legacy of Julie Packard, how she helped bring a deeper understanding of the ocean into focus, and in doing so, an ability to care.

One year ago, Packard announced she would step down as the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s first and only executive director. In the wake of that announcement, I began thinking about what it would look like to tell the story of her work—a cover story that was published in this week’s edition of the Weekly.

Of course, many people know Packard through her association with the Aquarium and its amazing exhibits. More complex is what she used the Aquarium to do. The paths she helped pave were many firsts for aquariums, and also many firsts in regional and national policy reform.

I tried to place myself in that time (before my own) during the Aquarium’s infancy, when the ocean was far less understood than it is today, and when conserving ocean resources—the backbone of our societies, whether or not we live on the coast—was a concept that had to be taught before meaningful change could occur.

What the Aquarium accomplished was instilling ocean literacy in a powerful way that could shape culture and influence policy. It emotionally immersed people in underwater worlds, delivering messages about how ecosystems are connected, how great white sharks were misunderstood and at risk, and how our favorite seafoods were on the brink of collapse.

I captured just a slice of a very rich history to provide some insight into Packard’s thinking, and understand what it was that placed her alongside the greats like Albert Einstein and Jane Goodall.

I wanted to understand what science communication meant at a time when people were just awakening to environmental threats, let alone realizing that we could actually do something about them.

As I was writing this story, I kept thinking: what an extraordinary challenge to build a model that could blend science, policy and ocean education. It’s astonishing to consider all that an aquarium can do—thanks to Packard at the helm, and remarkable teams of scientists, policymakers, conservationists and advocates she worked with along the way.

At the same time, I found myself reflecting on how we are now in a very different, and darker, era of media and science literacy, where new challenges in science communication have emerged.

Packard leaves behind an immense legacy in this space, but her successor will have to chart an entirely new, different path to confront a new set of challenges—namely, the questioning of science and the dismissal of threats to our natural resources.

She and I sat down over pastries and coffee last summer to talk about this, and to reflect on the past, present and future. There are lessons to be learned from her tenure—and hope, too.

Take a read. I hope you enjoy.