This post was originally published on here

In 1962, French geologist Michel Siffre did something no scientist had seriously attempted before. He voluntarily disappeared into a cave, cutting himself off from sunlight, clocks, calendars and almost all human contact. His aim was simple but radical: to understand how the human body perceives time when every external cue is removed.More than two months later, he emerged from a glacial cave in the French Alps wearing dark goggles to shield his eyes from sunlight. He had no idea what the date was. He had not spoken to another human in weeks. His thoughts felt slow and fragmented. He later described himself as feeling like “a half-crazed, disjointed marionette”.What he brought back would quietly transform modern sleep science.

Why he chose to go underground

At the time, scientists knew surprisingly little about circadian rhythms, the internal systems that regulate sleep, wakefulness and hormones. Most believed the human body depended almost entirely on the natural cycle of day and night.Siffre, trained as a geologist rather than a biologist, originally planned to spend just two weeks underground studying a newly discovered glacier. He soon decided that would not be enough. To truly understand the environment, he extended his stay to two months and chose to make himself the experiment.He would live without a watch, without daylight and without knowing the time.

Life inside the cave

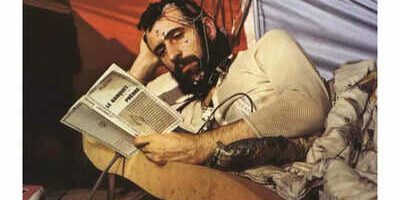

Siffre lived about 130 metres below the surface in complete darkness. The cave was icy, damp and cramped, with temperatures often below freezing and humidity close to 98 percent. His equipment was basic, and his feet were frequently wet. His body temperature sometimes dropped to around 34 degrees Celsius.He had no contact with the outside world except for a simple phone line used only to signal when he woke up. He was never told the time.There were no clocks. No sunrise or sunset. No imposed routine. He slept when he felt tired, ate when he felt hungry and worked when he felt alert.Slowly, his sense of time began to unravel.

When time stopped making sense

After weeks underground, Siffre believed only 34 days had passed. In reality, he had spent 60 days in the cave. His psychological sense of time had slowed dramatically.His internal clock also drifted far from the normal 24-hour cycle. In later experiments, his sleep–wake rhythm sometimes stretched close to 48 hours. He reported mood swings, memory lapses and moments of deep mental strain. Without daylight or clocks, days blurred into each other.Time, as a lived experience, began to dissolve.

The experiment that changed science

Siffre repeated the experiment several times, including a six-month isolation in 1972 that he later described as mentally brutal. Others followed him underground, reporting wildly irregular sleep patterns. One participant slept for more than 33 hours straight, alarming researchers monitoring him.These studies revealed that the human body maintains its own internal clock, independent of the Sun. The findings laid the foundation for chronobiology, the science of biological time. Decades later, research in this field would be recognised with a Nobel Prize awarded to scientists who built on principles Siffre helped uncover.

From caves to space

Siffre’s work attracted attention far beyond academia. During the Cold War, both NASA and the French military took interest. Space agencies wanted to understand how astronauts might cope with isolation and disrupted day–night cycles. The French navy needed answers for submariners spending months underwater without sunlight.His research helped shape how sleep cycles are managed in extreme environments.

Why his story still resonates

Emerging from the cave, Siffre said adjusting back to clocks and schedules was harder than adapting to darkness. Modern timekeeping felt artificial and oppressive.He died in 2022 at the age of 83, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape sleep science and our understanding of time itself.In an age ruled by deadlines, notifications and constant measurement, his story raises a haunting question: how much of our lives are shaped by clocks rather than biology?That tension is why Michel Siffre’s disappearance into the dark still fascinates today.