This post was originally published on here

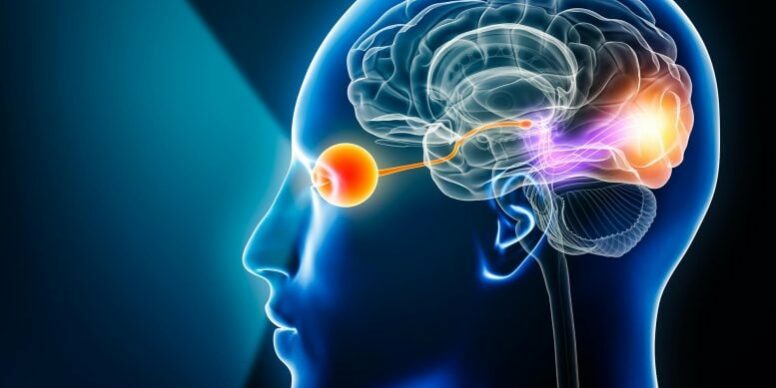

Your ability to notice what matters visually comes from an ancient brain system over 500 million years old.

The brain can make sense of the visual world even without relying on its most advanced outer layer, the cortex. A new study published in PLOS Biology shows that a far older brain structure, known as the superior colliculus, has the neural machinery needed to carry out essential visual computations. These processes allow the brain to separate objects from their background and determine which visual signals matter most in a given space.

The research also shows that these ancient circuits, which exist in all vertebrate brains, can independently produce center surround interactions. This basic visual principle helps the brain detect contrast, edges, and visually important features in the environment.

“For decades it was thought that these computations were exclusive to the visual cortex, but we have shown that the superior colliculus, a much older structure in evolutionary terms, can also perform them autonomously,” explains Andreas Kardamakis, head of the Neural Circuits in Vision for Action laboratory at the Institute for Neurosciences (IN), a joint center of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Miguel Hernández University (UMH) of Elche, and principal investigator of the study.

“This means that the ability to analyze what we see and decide what deserves our attention is not a recent invention of the human brain, but a mechanism that appeared more than half a billion years ago.”

The Brain’s Built In Visual Radar

The superior colliculus functions like a biological radar. It receives direct signals from the retina and evaluates them before visual information reaches the cerebral cortex. Its role is to quickly determine which elements in the visual scene are most relevant.

When an object moves, flashes, or suddenly enters view, the superior colliculus is often the first brain structure to respond. It helps guide eye movements toward these changes, allowing the brain to rapidly orient attention.

How Scientists Studied Ancient Visual Circuits

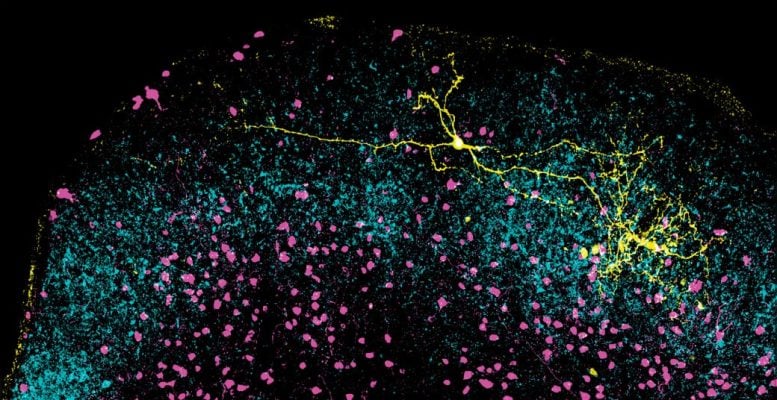

To understand how this structure works, researchers used a combination of advanced techniques, including patterned optogenetics, electrophysiology, and computational modelling. By activating specific retinal connections with light and recording responses in mouse brain slices, the team was able to observe how neurons in the superior colliculus interact.

These experiments showed that when surrounding visual areas are stimulated, the response to a central signal is suppressed. This pattern is a defining feature of center surround interactions and was confirmed using cell type specific transynaptic mapping and large scale computational models.

“We have seen that the superior colliculus not only transmits visual information but also processes and filters it actively, reducing the response to uniform stimuli and enhancing contrasts,” says Kuisong Song, co first author of the paper. “This demonstrates that the ability to select or prioritize visual information is embedded in the oldest subcortical circuits of the brain.” The findings indicate that the brain’s ability to highlight important visual information does not depend only on higher cortical regions but is rooted in mechanisms shared across all vertebrates.

Rethinking Visual Processing and Brain Evolution

These results challenge the long held view that complex visual processing is limited to the cortex. Instead, they support a more layered organization of the brain, where ancient structures do more than pass information along. They also carry out critical computations needed for survival, such as spotting predators, following prey, or navigating obstacles.

“Understanding how these ancestral structures contribute to visual attention also helps us understand what happens when these mechanisms fail,” Kardamakis notes. “Disorders such as attention deficit, sensory hypersensitivity, or some forms of traumatic brain injury may partly originate from imbalances between cortical communication and these fundamental circuits.”

The research team is now expanding this work to in vivo studies to explore how the superior colliculus influences attention and limits distraction during goal directed behavior. Learning how visual distractions are translated into actions could shed light on the biological roots of attention related disorders, especially in a world increasingly shaped by visual technology.

Global Collaboration Behind the Study

The study was carried out through an international collaboration involving the Karolinska Institutet, the KTH Royal Institute of Technology (both in Sweden), and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT, USA). Teresa Femenía, a researcher at IN CSIC UMH, also played a key role in developing the experimental work.

A Shared Evolutionary Blueprint for Attention

Related to this research, Andreas Kardamakis and Giovanni Usseglio recently published a chapter in the Evolution of Nervous Systems series, edited by JH Kass (now appearing in Elsevier, 2025). The chapter explores the evolutionary history of subcortical visual circuits across species.

The authors review how brain structures similar to the superior colliculus, found in fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, all follow the same basic principle. They integrate sensory input with motor control to guide attention and eye movements.

This brain architecture has been preserved for more than 500 million years and provided the foundation on which the cortex later developed more advanced cognitive abilities. “Evolution did not replace these ancient systems; it built upon them,” says Kardamakis, adding, “We still rely on the same basic hardware to decide where to look and what to ignore.”

Reference: “Recurrent circuits encode de novo visual center-surround computations in the mouse superior colliculus” by Peng Cui, Kuisong Song, Dimitrios Mariatos-Metaxas, Arturo G. Isla, Teresa Femenia, Iakovos Lazaridis, Konstantinos Meletis, Arvind Kumar and Andreas A. Kardamakis, 16 October 2025, PLOS Biology.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3003414

This research was supported by Spain’s State Research Agency – Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence, the Generalitat Valenciana through the CIDEGENT program, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Brain Foundation, and the Olle Engkvist Foundation.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.