This post was originally published on here

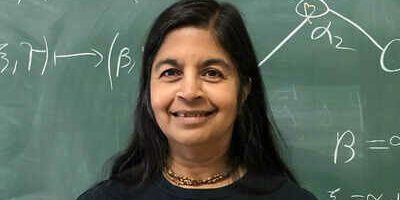

For much of modern history, mathematics has worked in silence. It does not stage revolutions with dramatic announcements, nor does it announce its presence with visible machines or laboratory breakthroughs. Its influence is subterranean, embedded in fibre-optic cables, encrypted messages, climate simulations, and the algorithms that quietly govern daily life. This week, that invisible power stepped into the public eye when Indian-origin mathematician Nalini Joshi was named New South Wales’ Scientist of the Year, becoming the first mathematician to receive the state’s highest scientific honour.The recognition is not simply a personal milestone. It is a rare acknowledgment of mathematics as a driving force behind contemporary science and technology and of a scholar whose career has steadily reshaped how abstract theory connects to the real world.

From Fort Street to Princeton

Joshi’s academic journey began in Sydney, where she attended the academically rigorous Fort Street High School, a training ground for some of Australia’s brightest minds. She went on to earn her Bachelor of Science with honours in 1980 at the University of Sydney, displaying early promise in a discipline that rewards precision, patience, and imagination in equal measure.Her path then led her to the intellectual crucible of Princeton University, where she completed her PhD under the supervision of Martin David Kruskal, one of the most influential mathematical physicists of the 20th century. Her doctoral thesis, The Connection Problem for the First and Second Painlevé Transcendents, placed her firmly within the elite world of integrable systems, a field concerned with nonlinear equations that defy simple solutions yet govern many natural and technological phenomena. It was demanding, rarefied work. But it would later prove to be foundational.

Building a career in Applied Mathematics

After a postdoctoral fellowship at the Australian National University in 1987, followed by a research fellowship and lectureship, Joshi began carving out a career that combined intellectual depth with institutional leadership.She joined the University of New South Wales in 1990, rising to senior lecturer by 1994. In 1997, she secured an Australian Research Council senior research fellowship, a mark of national recognition, which she took up at the University of Adelaide, becoming an associate professor soon after.Her return to the University of Sydney in 2002 as Chair of Applied Mathematics marked a historic moment. Joshi became the first woman appointed Professor of Mathematics at the university, a breakthrough that resonated far beyond her own discipline, challenging entrenched gender hierarchies within Australian academia.She would go on to serve as Director of the Centre for Mathematical Biology, Head of the School of Mathematics and Statistics, and a sustained leader within the institution. But her influence extended well beyond administrative titles.

Mathematics that shapes the world

At the heart of Joshi’s work lies the study of integrable systems, equations that describe complex, nonlinear behaviour. These are not tidy textbook problems. They are the mathematics of turbulence, wave motion, optical systems, and fluid flows, systems where small changes can trigger dramatic consequences.The applications are vast. Fibre-optic communications, which underpin the global internet, rely on precisely the kinds of equations Joshi studies. Climate modelling, grappling with chaotic and sensitive environmental systems, depends on advanced mathematical frameworks to forecast future risks. Nonlinear physics and emerging quantum systems draw directly from the theoretical ground her research helps cultivate.Colleagues often describe her work as a bridge: Deeply abstract, yet profoundly practical. Its effects are rarely visible, but they are everywhere.

Securing a quantum future

In recent years, Joshi has turned her attention to one of the most pressing technological challenges of the coming decades: quantum computing and its implications for cryptography.Cryptography protects the digital scaffolding of modern life, online banking, digital payments, government systems, and private communications. Quantum computers, once fully realised, threaten to dismantle many of today’s encryption methods with unprecedented computational power.Joshi has been forthright in her warnings. She has argued that governments and industries are dangerously underprepared for a post-quantum world, particularly in Australia, where the pool of specialists capable of developing post-quantum cryptography remains small. Her message is clear: Without sustained investment in advanced mathematics now, digital security later will be fragile at best.It is a reminder that mathematics is not an academic luxury. It is strategic infrastructure.

Leadership beyond the blackboard

The New South Wales Scientist of the Year award also recognises Joshi’s role as a mentor, advocate, and reformer. In 2015, she co-founded and co-chaired Science in Australia Gender Equity (SAGE), an initiative aimed at improving the retention and advancement of women in STEM using the internationally recognised Athena SWAN framework. She has since served on the SAGE Expert Advisory Group, helping shape national conversations about equity in science.Her advocacy has been measured, evidence-driven, and persistent, qualities that mirror her approach to mathematics itself.

A milestone that redefines recognition

That a mathematician has finally been named NSW Scientist of the Year is not incidental. It signals a broader shift in how scientific contributions are understood. In an era defined by climate instability, digital vulnerability, and technological acceleration, mathematics is no longer merely supportive; it is central.Nalini Joshi’s career embodies that truth. From Fort Street classrooms to Princeton seminar rooms, from abstract equations to national policy debates, she has spent decades demonstrating how the most theoretical ideas can shape the most practical realities.In honouring her, New South Wales has done more than recognise an individual. It has, at last, acknowledged the quiet discipline that holds the modern world together.