This post was originally published on here

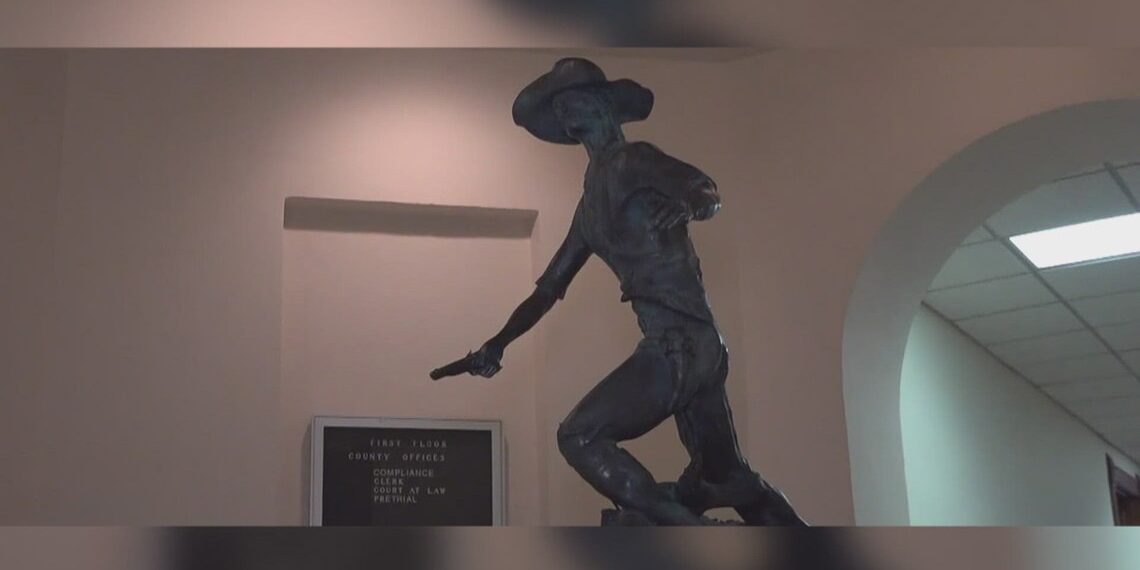

Coryell, born in Ohio in the late 1700s, came to Texas in the early days of the settlement period and became one of the Republic’s first Rangers.

FALLS COUNTY, Texas — Nearly two centuries after he died on the frontier, one of the Republic of Texas’ earliest lawmen has finally been found.

James Coryell, a Texas Ranger and early pioneer whose name now graces Coryell County, was killed in 1837 and buried near the site of a violent encounter with Native Americans. For decades, the precise location of his grave was lost to time — until a combination of oral history, archaeology and cutting-edge science helped rediscover it near Bull Hill Cemetery in Falls County.

Coryell, born in Ohio in the late 1700s, came to Texas in the early days of the settlement period and became one of the Republic’s first Rangers. He was a friend and contemporary of famed frontiersmen such as James and Rezin Bowie, and he played a role in early Indian conflicts as settlers expanded into Central Texas.

On May 27, 1837, Coryell and a small group of fellow Rangers were scouting near the abandoned settlement of Sarahville de Viesca — a once-bustling frontier post near present-day Marlin — when they were ambushed by Caddo warriors. Accounts differ on the precise nature of his wounds, but he was shot and scalped during the attack. Fellow Rangers reportedly found him alive and brought him back to the settlement, where he died two days later.

His burial was unceremonious and its location was not formally recorded. Over time, the site was forgotten as the frontier moved west and the settlement fell into ruin. The area later became part of a plantation, and the nearby Bull Hill Cemetery was established for enslaved African Americans and their descendants.

The trail to Coryell’s resting place resurfaced thanks to oral histories passed down through generations, including narratives from formerly enslaved residents of the area preserved during the 1930s Works Progress Administration. One account described a grave off the southern edge of Bull Hill that had collapsed and been covered with stones to keep the spirit at peace.

In 2010, archaeologists with the Texas Historical Commission uncovered a grave shaft beneath a cluster of rocks near Bull Hill, initiating a multi-year investigation. With assistance from forensic anthropologists at the Smithsonian Institution, the remains were exhumed and analyzed.

Initial attempts to extract viable DNA for comparison with living relatives proved inconclusive due to deterioration. But advances in technology and renewed analysis in 2019 yielded enough genetic material to finally confirm that the remains were those of James Coryell.

In addition to DNA, physical evidence such as cut marks consistent with scalping and a dark substance on the skull interpreted as a poultice supported historical accounts of Coryell’s death. A sociocultural context — the proximity of the site to Bull Hill and its use over many decades as a burial ground — further strengthened the case.

The rediscovery of his grave has sparked broader interest in the early history of Texas Rangers and frontier life, illuminating a period when the boundaries between legend and reality were thin. A documentary funded in part by a grant is underway to bring Coryell’s story and the diverse history of early Texas to a wider audience.

Coryell County, created in 1854, was named in his honor — a tribute long delayed, but now backed by the scientific confirmation of where one of its namesakes truly rests.