This post was originally published on here

Forensic scientist Brian Andresen arrived at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, a cemetery in Glendale, California, with massive wrought iron gates—the largest in the world—and rolling green hills, a little before 7 a.m. on a spring day in 1999.

A natural problem solver, Andresen, an organic chemist and founder of the Forensic Science Center at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, had a crucial job to do. Investigators at the Glendale Police Department had been looking into the suspicious deaths of patients at a nearby hospital and believed they might have a serial killer on their hands. A year earlier, a respiratory therapist at the Glendale Adventist Medical Center named Efren Saldivar had confessed to the killings. The media was calling him “the Angel of Death.” Now, a task force headed by Glendale robbery-homicide Sergeant John McKillop was working rigorously to prove Saldivar’s guilt. It wasn’t going well. Doctors had initially determined that all of the deaths at the hospital that had occurred the final two years that Saldivar was on duty—171 in all—had been from natural causes. And just days after admitting guilt, Saldivar had recanted.

The police suspected that Saldivar had injected patients using a syringe filled with lethal doses of paralyzing drugs. But lacking evidence, they were stuck. They had called in Andresen to help them search for the presence of those drugs in the bodies of deceased patients. Finding trace elements of a drug in badly decomposed corpses wouldn’t be easy, but it was their best and possibly only chance of bringing a suspected serial killer to justice.

Andresen stood in the predawn light, waiting for sunrise and his work to begin. He had reason to be optimistic: One of those drugs, Pavulon, is made of sturdy molecules that don’t break down easily, he told the cops. And his lab gave him access to some of the most advanced mass spectrometry tools of his time, machines that could identify the smallest traces of chemicals. When the exhumations finally got under way that morning, Andresen worked to ensure that any evidence they gathered didn’t become contaminated, which would make it inadmissible in court. He examined soil from adjacent plots in case drugs from other remains had leaked into the burial plots and tainted the samples. Water from the sprinkler systems that pooled in the coffins (called “crypt water”) had to be checked for chemicals. The embalming fluids had to be examined to make sure there were no extraneous compounds that would interfere with any later findings of Pavulon.

Still, some of Andresen’s peers were skeptical.

“They thought that the sample, after two, three years in the ground, would be totally degraded,” Andresen says.

McKillop had his doubts too. We’re never going to find this drug, he thought.

If anyone could find traces of the drug, it was Andresen and his team back at Lawrence Livermore.

By 1999, Andresen had led the lab for nearly a decade. The core of his work relied on mass spectrometry, a relatively new technology at the time that allowed the forensic scientists there to identify the tiniest molecules of chemicals left at crime scenes. The lab gained a reputation for solving crimes no one else could. Its renown had even leapt into pop culture when the novelist Tom Clancy, in his best-selling Power Plays book series, described the lab as having “the best group of crime detection and national security experts in the business.” Others referred to it more poignantly as the “Lab of Last Resort.”

Andresen, now 78, didn’t set out to solve crimes. He had been an aspiring oceanographer studying chemistry and biology at Florida State University in the 1960s. There he took a summer job maintaining one of the country’s first mass spectrometers. Back then, the device was used for simple chemical analysis. The most basic form of mass spectrometry design, electron impact, functions by shooting an electron beam at vaporized organic chemicals inside a vacuum. When the beam hits the molecules, it shatters them into parts depending on the stability of the molecules. The shatter pattern provides a “fingerprint” for each molecule, allowing for identification.

By the time he enrolled in graduate school at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1969, Andresen knew enough to study under Klaus Biemann, known as the “father of organic mass spectrometry.” Soon after, astronauts started returning from the early Apollo missions with hundreds of pounds of rocks from the moon. Andresen was part of a team at MIT that examined the rocks using mass spectrometry. While explaining the process on TV, Andresen emphasized how sensitive mass spectrometry is.

“If I have a drop of blood, I can use mass spectrometry and see every chemical in that blood and look for overdoses or inborn errors of metabolism, all sorts of biochemical abnormalities,” Andresen said.

Doctors around the nation and the world took him at his word, and soon Andresen was being asked to solve overdose cases of unknown cause. He began work at Livermore in 1983, setting up an environmental science lab. For one of his first projects, he used mass spectrometry to identify carcinogens in overcooked meat. Over the years Andresen found himself fielding numerous investigative requests that required a restricted facility where technicians could enforce a clear chain of custody to prevent evidence from being questioned in court. He realized he needed a secure, sterile facility to do that work. In 1991 he got his wish: The Forensic Science Center at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory opened in a retrofitted building that had not previously handled a large amount of chemicals; to function accurately, those mass spectrometers needed a completely sterile room.

Armando Alcaraz, an analytical chemist who is now 69, was one of the first to join Andresen’s research team. “He kind of wandered over,” says Andresen. Back then, Alcaraz was using gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance analysis in the lab’s high-explosives research facility. Just a few years out of graduate school at San José State University, Alcaraz remembers chatting with Andresen about what he was doing—and thinking, that’s pretty cool stuff.

At the time, Alcaraz explains, law enforcement agencies were using traditional forensics methods, such as analyzing fingerprints and hair samples. “But the actual chemical signatures were not something that folks looked at that closely. And I think that was sort of the groundbreaking part of what Brian [Andresen] was able to do.”

All of this was happening at the larger Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, located on the eastern edge of the San Francisco Bay Area. The 770-acre campus resembles a quiet university with flat streets, plenty of bike riders, and several cafeterias. It was founded by two physicists, E.O. Lawrence and Edward Telleras, during the Cold War in 1952 as a branch of University of California Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley. The lab’s original mission was to advance nuclear weapons development, specifically the hydrogen bomb. In 1971 the lab separated from the university. A decade later it was named a national laboratory, funded by the federal government.

Today the main lab employs more than 6,000 people and houses the world’s largest laser and fastest supercomputer. Scientists there are leading the nation’s efforts on nuclear fusion and have the contradictory responsibilities of advancing the U.S. nuclear arsenal while helping to stem the spread of weapons of mass destruction elsewhere around the globe.

Researchers at the Forensic Science Center have investigated some of the country’s most infamous acts of terrorism. Andresen and his team examined evidence left after several of the Unabomber’s attacks. Although their analysis was insightful, it didn’t lead them to Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber. (The breakthrough came in 1996 when Kaczynski’s brother turned him in.) Then, two years later, Andresen determined the type of bombs being used by the Fremont bomber, which at the time were the largest and most electronically sophisticated domestic pipe bombs that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms had ever dealt with.

But Glendale’s Angel of Death case was different; forensic scientists at the lab had a chance to bring the suspected killer to justice.

The investigation into Saldivar began with a rumor in the halls of the Glendale Adventist Medical Center.

In February 1998 a tipster reported that a nurse who worked at the hospital had told him that another employee was helping patients die quickly, according to reports in the Los Angeles Times. At the time the tip came in, the hospital had already suspected one of its employees. A year earlier, it had investigated Efren Saldivar after another respiratory therapist at the hospital told administrators that he had heard that Saldivar was carrying around a “magic syringe,” which he used to inject patients with lethal doses of paralyzing drugs.

Located at the base of the Verdugo Mountains and next to the Ventura Freeway, the Glendale Adventist Medical Center is imposing and had more than 450 beds at the time. Founded in 1905 by the Seventh-day Adventist Church—a year before the city of Glendale was incorporated—Glendale Adventist was known for its religious lineage. Saldivar had begun working there in 1989 as a respiratory therapist, a role that required him to provide breathing treatments. Before putting a tube in a patient’s windpipe to help them breathe, he would administer Pavulon to relax the patient’s muscles. This was normal procedure. But because Pavulon renders the breathing muscles useless, too much of it can cause the patient to suffocate.

Based on the respiratory therapist’s earlier report and the anonymous tips, hospital administrators were worried that Saldivar might have intentionally injected his patients, many of whom were over 50, with lethal doses of the drug. If that was the case, the number of patients who were potentially drugged by Saldivar would make him one of the most notorious killers in U.S. history.

Initially, the hospital hadn’t found compelling evidence of foul play. According to police involved in the case, the hospital noted that the number of patients who died on Saldivar’s shift was in line with the rate experienced by other respiratory therapists. Plus, there had been media reports that the respiratory therapist who’d made the claims did not get along with Saldivar. Maybe the informant had an axe to grind.

With the new accusations, however, hospital administrators asked police to look into it, says McKillop. The sergeant assigned detective Will Currie to the case as its primary investigator and tasked him with finding the tipster and chasing other leads. It took about two weeks for the detective to find the tipster, and when he finally did, Currie claims, the man was uncooperative. “He didn’t want to talk to us, and I had to put my shoe in the door so he couldn’t close it on me,” Currie says. But the detective, who had grown up in South Africa and once worked as a game warden there, kept going. He eventually found the woman who the tipster said had given him the information.

But she told police she had made it all up, according to the Los Angeles Times. The police had nothing.

Running out of options, Currie went back to Saldivar and asked him to undergo a polygraph test. “If he had come in and said, ‘I didn’t do anything’, we probably would have dropped it that night,” says Currie.

Glendale, a city in Los Angeles County with a population close to 200,000 at the time, did not have a polygraph examiner in its police department. So Currie called Ervin Youngblood, a senior polygraph examiner with the Los Angeles Police Department, for help. When Youngblood showed up at the Glendale station, McKillop had already left for the night.

Youngblood was still setting up when Saldivar entered. The 28-year-old, who lived in nearby Tujunga, wore glasses and had a round, soft face that made him look younger than he was. He had worked at Adventist for nine years. He lived with his younger brother and his parents. He was a polite guy who had recently taken up bike riding and helped support his parents. He was a handyman and a nurse’s aide, a young man who once wanted to join the tough crowd at school.

Although polygraphs aren’t admissible in court, what is said in the preliminary interview while preparing the subject for the test can be used, under certain circumstances. Youngblood began with the usual questions. Where was Saldivar born? Brownsville, Texas. How much had he slept in the last 24 hours? Three hours. Did he have any drugs or medications in his system? Mountain Dew. Does he know why he is here? To clear himself.

“To clear you up about what?” Youngblood asked.

“About, uh, the accusations.”

“Why don’t you tell me about the accusations?”

Saldivar said he had been accused of injecting patients with drugs and killing them. Youngblood then asked Saldivar if he was an “angel of death.” “No,” Saldivar told him.

“Have you done anything like that?” Youngblood asked.

“. . . there’s been a lot of times where I’ve not actually done it, but kind of assisted in [it] either directly or indirectly.”

Saldivar told Youngblood that he had helped people who were “close to the end,” according to police reports filed after the interview. Then Youngblood again asked Saldivar if he thought he was an angel of death.

“Yeah, I do.”

In his conversation, Saldivar said he had used Pavulon to kill patients and admitted to directly or indirectly causing the death of more than 100 patients, although he did not give the names of his victims or provide exact dates that would have aided the case.

Youngblood had already set the polygraph process in motion. But he never got to the actual lie-detector part because Saldivar almost immediately began confessing. When the interview was over, Youngblood looked at Saldivar and remembers thinking that he never would have suspected him. “He doesn’t fit the profile of somebody who would do something like that.” Youngblood believes the interview was the first time the label “Angel of Death” was used in connection with the case. Saldivar said he liked the term because it reminded him of a “dude” on TV. The media embraced it because it was catchy. The epithet stuck.

Glendale police officers promptly arrested Saldivar but were unable to find evidence to charge him with a crime. It’s what law enforcement calls corpus delicti, or “body of the crime”: the principle that a person cannot be convicted of a crime until authorities have proof that something illegal has occurred. Then Saldivar recanted; police released him days later.

To secure a conviction, the team assembled by McKillop would need to show that some of the 171 deaths that happened on Saldivar’s watch were not natural—that he had intentionally administered lethal levels of paralyzing drugs. For that, they’d have to exhume the bodies—a morbid, time-consuming, and expensive process. They began by narrowing the list to just the most likely victims.

The team scoured medical records for signs of unexpected deaths, those with no history of treatment with Pavulon, and especially anyone who had come under the care of Efren Saldivar. They displayed their findings on a wall, highlighting the names of victims who matched their criteria. They called it their “death board.”

“Every one of us were, you know, just dumb cops, I guess,” says McKillop, an affable former athlete who is now 63. “And we all had to learn how to read medical charts, learn medical terminology, what to look for.”

After more than a year they narrowed the list to 20 and began digging up the bodies—one a week for 20 weeks. The corpses went to the morgue, and then McKillop and Currie delivered tissue samples from different body parts to Andresen at the Forensic Science Center, making the 330-mile drive together weekly. It was important to maintain a clear chain of custody.

Like many cops, McKillop frequently had nightmares. Now he started seeing people rising from the dead in his dreams. But the time spent with Andresen gave him hope. Maybe this brilliant scientist could crack the case. Once, after handing the samples over to Andresen, McKillop remembers asking him how to make an atomic bomb.

“We were having a beer at a restaurant, and he pulled out a napkin and he drew a diagram of how things were,” says McKillop. “I thought that was hysterical.”

Andresen had a way of explaining things that didn’t make McKillop feel stupid. “I think he’s a genius, but he’s so down to earth.”

All the while, Andresen, the organic chemist who had helped solve some of the nation’s most puzzling cases, had been busy conducting research of his own. Before the bodies arrived, while he was still testing methods to extract Pavulon from remains, Andresen visited the deli at a nearby Safeway store.

“Do you have a liver sample of something you want to just get rid of?” he recalls asking the butcher. A block of beef liver was handed over. Andresen let it sit in the lab decomposing for a while so it would better represent exhumed remains. “People were not happy with me,” he says of the smell.

When it was ripe enough, Andresen mixed the tissue with Pavulon and tried to extract the drug. No luck. He returned to the butcher. Beef was followed by pig. Weeks passed as he tried different extraction methods without luck.

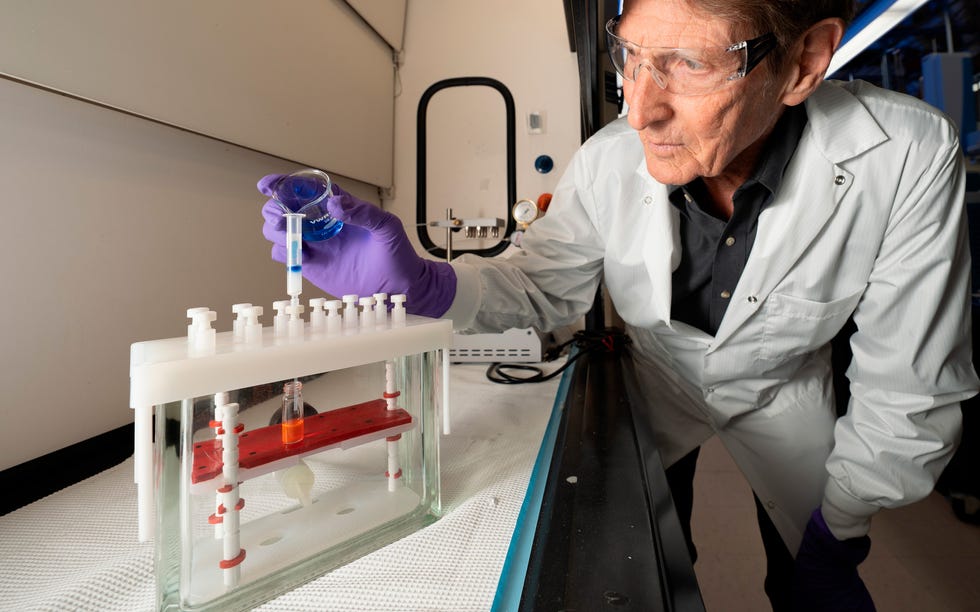

Finding a way to extract Pavulon was just another difficult problem for Andresen to untangle. Luckily he didn’t have to go far for a solution. Experts at the Forensic Science Center were working on more than just the Saldivar case. Some were conducting research for an ongoing program of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons that investigates potential uses of chemical weapons around the world. The work involves using single-phase cartridges, syringelike objects with a filter inside, to separate the lethal elements of chemical weapons from other substances. Andresen tried different polymer filters in the cartridges to isolate instances of Pavulon from the decomposed tissues. Once he found the right one, Andresen extracted the Pavulon. He then used mass spectrometry to confirm the identification.

About the size of a mini refrigerator, the blocklike spectrometers reveal little to the naked eye. It is the computer screens next to the analyzers that show the results, the weights of the molecules, when they might have separated from the larger sample—all clues that can be used to identify them. Andresen had found a way to detect Pavulon, but he wasn’t certain the method would work on exhumed human corpses. Now he was about to find out. When the samples arrived from Glendale, Andresen and Alcaraz lined them up, numbered them, and logged them. The stench of decaying human organs was so strong that it overpowered the ventilation system; it filled the room and permeated their clothes. It lingered even after using bleach to sanitize the equipment, says Alcaraz.

Heart tissue, lung tissue, intestines, stomach, kidney: At least 12 different tissue samples were taken from each possible victim. At the lab, a section weighing about 10 grams was cut from each sample. Andresen would then weigh the exact amount before adding a salt solution and combining it in a stainless steel blender for 30 to 60 seconds.

“Blended to a thick solution,” Andresen says.

“Like a lotion,” Alcaraz adds.

They poured the solution through a funnel, passed it by a cartridge, and analyzed it in the mass spectrometer. Days, weeks, months passed without finding any Pavulon in any of the samples. And then: “I got a hit,” Andresen recalls. Alcaraz ran the sample again to check Andresen’s work. Pavulon was indeed present.

“We were like, jumping around, going, ‘Yes, we got it!’” Alcaraz says.

Andresen called McKillop the next day.

McKillop was pleased; he knew the tissue they were working on belonged to a Glendale Adventist patient who had been given Pavulon legitimately. It had been a controlled test to verify whether Andresen’s method worked.

Andresen went back to work, finding five more positive cases of Pavulon. Each of those appeared to be from a victim of Saldivar.

Salbi Asatryan, a 75-year-old Armenian immigrant, had been found dead in her room at Adventist on December 30, 1996, three days after being rushed to the hospital in acute respiratory failure. It was after her death that the respiratory therapist had heard a colleague refer to Saldivar’s “magic syringe.”

Eleanora Schlegel was found dead on January 2, 1997. She was 77 and had spoken to her son Larry just days before. She had been admitted to the hospital for pneumonia on December 30.

Jose Alfaro, a native of the Philippines, aided the Allies during WWII. He was 82 years old when he died on January 4, 1997. His wife, Cecilia, told the Los Angeles Times that they had married in 1941 when she was 26. “Who is he [Saldivar] to kill?” she asked.

Myrtle Brower was an 84-year-old intellectually disabled woman who had been cared for by her family for many years. She died on August 28, 1997.

Balbino Castro had been given Pavulon legitimately as part of his treatment, but police believed the amount of the drug found in his body was more than what his treatment called for. Castro and Luina Schidlowski, another victim, were both 87. Castro died on August 15, 1997, and Schidlowski on January 22, 1997.

The lethal doses of Pavulon administered by Saldivar paralyzed the patients, explains Andresen. “Once it gets in your bloodstream, you can’t breathe, you can’t move, you can’t push any buttons or anything,” he says. Slow suffocation follows, “which probably is a horrible death.”

In October 2001 a Los Angeles County grand jury indicted Saldivar on six counts of murder and one count of attempted murder. The attempted murder was for Jean Coyle, a 62-year-old who survived a potentially lethal drugging on February 26, 1997. She died three years later of other causes.

By January 2001, police had the evidence they needed to arrest Saldivar. He confessed to the crimes again and in March 2002 pleaded guilty to all seven charges under a plea bargain. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Retired Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley says, “Livermore lab was the key to establishing the corpus delicti.” Without the Forensic Science Center’s work, the prosecution would not have been able to use Saldivar’s two confessions.

After his first confession, Saldivar made a number of media appearances in which he denied guilt. “He loves to talk,” says Currie. “He doesn’t—he won’t—shut up.” Yet in the years since then, Saldivar has said little. He is 55 now and incarcerated at California State Prison, Corcoran. When asked by letter if he would speak, Saldivar wrote: “No thank you. Respectfully Efren.” Then he added a postscript. Should a reporter want to correspond with other inmates, they should include a self-addressed stamped envelope next time.

Andresen retired from the Forensic Science Center in 2003. It is now on its fifth director, Audrey Williams, who is the first woman to lead the lab. Today the facility employs a core staff of about 25 scientists working in a dozen lab rooms, most with several mass spectrometers inside. The humming of the machines’ vacuum pumps, which maintain an air-free system for high-sensitivity analysis, provides a constant background noise.

The lab’s work on sample analysis is similar to how it was done when Andresen ran the show, except that it now focuses more on broader national security issues. Williams explains that the scientists analyze chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats and ensure that the lab is prepared to detect them. Mass spectrometry, which has become more precise and versatile in the years following the Angel of Death case, remains at the core of its work.

Smaller machines and more-advanced computers have made mass spectrometry more accessible to law enforcement agencies. Today, any number of labs around the country would be able to do the kind of groundbreaking work Andresen’s team accomplished two decades ago at Lawrence Livermore. What the center handles now are the “problem children,” Williams says. When that work does arise, she often calls on Andresen. “He’s got a lot of those skills from the early days and that true traditional forensic expertise that a lot of our team doesn’t have,” Williams says.

When not consulting on cases, Andresen spends his time playing the drums in several swing bands and repairing antique clocks and watches—a hobby he picked up while investigating the timing mechanisms used during a rash of house bombings in 1998.

McKillop and Currie, both retired from the Glendale police force, still field calls on the Angel of Death case. One thing that bothers McKillop is the perception that Saldivar’s actions were a form of euthanasia. McKillop doesn’t think that’s what was happening. “[The patients] were not circling the drain.” He also wishes they’d been able to establish that more than just six of the deaths on Saldivar’s watch were intentional victims. “I guess that’s the one thing we’ll never be able to prove,” McKillop says. “By his own confession, it’s probably 100-plus.”

Even with the six known victims there are unknowns. Many of the family members have chosen not to speak, wanting to avoid reliving what happened long ago. Matthew B.F. Biren, an attorney who represented the family of Jose Alfaro, told the Los Angeles Times in 2001 that it was “very upsetting” for the family to learn he had died by “inappropriate contact.” In the same article, Eleanora Schlegel’s son Larry, who has since died, said that learning the truth of his mother’s death was extremely difficult to process: “I think I’ve put up a lot of walls.”

One victim who received little media attention is Luina Schidlowski. It is unclear if she had children. Her headstone remains at Forest Lawn cemetery, the site of those police exhumations decades ago. It rests atop the grounds’ rolling hills, which afford visitors broad vistas of Glendale and Los Angeles. Beneath Schidlowski’s name are the dates she lived—April 14, 1909, to January 22, 1997—and a single line: “A unique woman of great love and sensitivity.”