This post was originally published on here

The Chelsea Football Club, which plays in the English Premier League, recently named Liam Rosenior as its new manager. But will this former player’s style change Chelsea’s play for the better?

That’s the kind of question that a new research group at Northeastern University, operating out of the Network Science Institute, hopes to answer. By analyzing the statistics and movements of both teams and individual players across thousands of matches, they can build dynamic networks of interactions that predict how games will unfold.

While they’ve largely focused on soccer for the past year, their methodology can apply to any sport, from those with complex team dynamics, like soccer, to more individual sports, like tennis or even gymnastics.

Gathering the squad

Brennan Klein, an assistant teaching professor in the department of physics and a member of the Network Science Institute (NetSI) at Northeastern, says the research group was an idea he and his colleagues discussed for a long time before kicking off, uncertain whether they would have access to as much data as they would need.

A philanthropic donation, along with support from Sternberg Family distinguished professor Alessandro Vespignani, gave them access to that data. “We have almost 17,000 individual matches,” Klein says, covering both women’s and men’s soccer.

NetSI Sport, as it’s styled, gathers all kinds of statistics from these matches, from passing volume and accuracy to shots made and passes made under pressure, to the movements of individual team members.

“The goal is to come up with tools and analyses, and even theories, that transcend different sports,” Klein says, to identify what he calls the “structural signatures” of individual sports that set them apart and occasionally make them more similar.

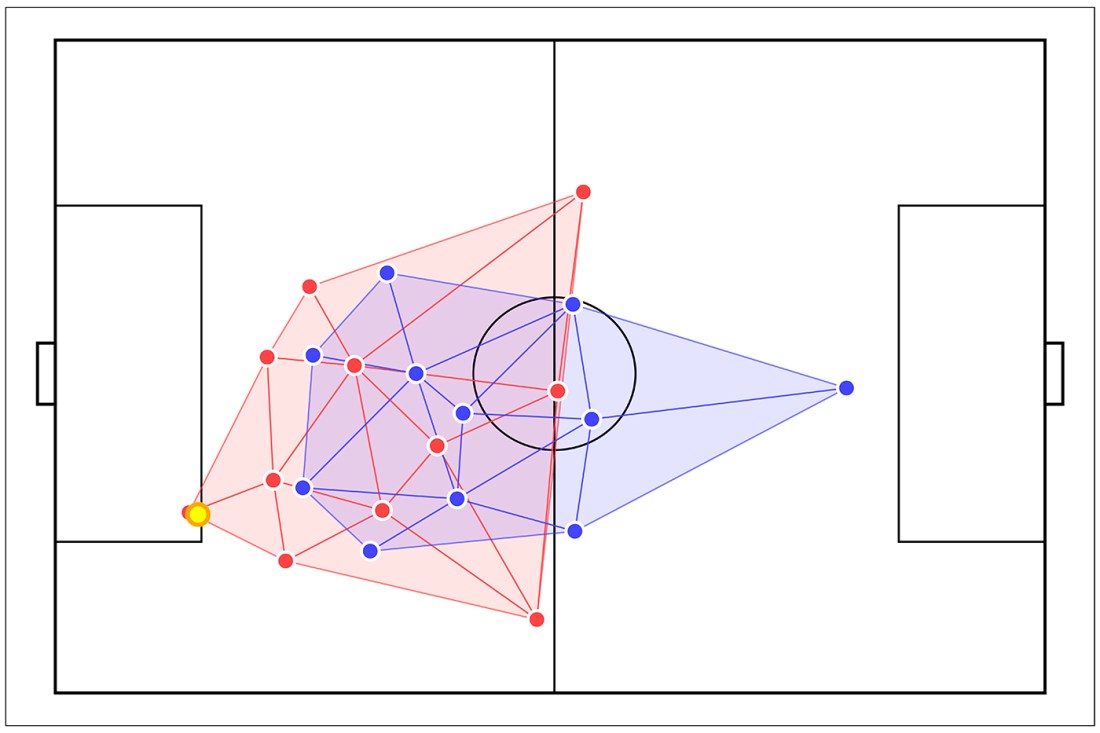

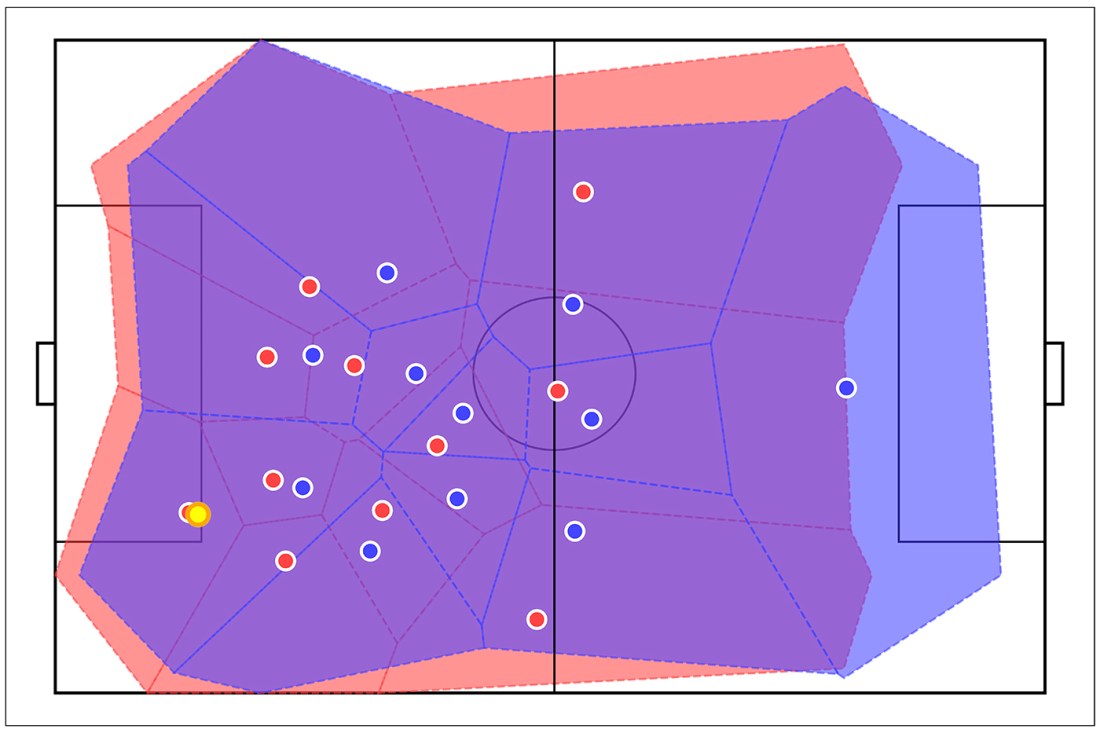

Klein says that they brought on Maddalena Torricelli last April as a postdoctoral researcher to focus on the networks behind sports analytics. “We are dealing with how to represent all the events happening on the pitch, through a network,” she says.

The language of the game

Both Klein and Torricelli say that one of the most exciting directions their research has taken is toward the linguistic, the ways in which a sports match can be treated like a conversation.

A match can be broken down much like analyzing text, Klein says. Sentences can be broken into clauses and clauses into individual words. Several of their projects, he continues, apply the same logic to soccer.

“You can think about this sequence of pass, carry, dribble, turn over the ball, pass again, carry, shoot, et cetera, as a sort of linguistic phenomenon,” he says. If this is true on a soccer pitch, then the researchers can consider the two teams in continuous conversation.

You can consider each element in that sequence, Klein says, as a node in a network, the way words are arranged into strings form sentences. The specific networks of individual teams or players, they’ve discovered, are unique and identifiable, like a signature.

These network signatures are also keyed to specific moments in time, which allows for more interesting experiments. “Well, Barcelona from 2006 looks like this. Barcelona today looks like this. What if they played each other?” he asks.

You can do the same thing with individual players, he continues. What would it look like to take one of the greats, say, Lionel Messi circa 2008, and have him play for a team he never joined? “You can see his signature imprinted in this network,” Klein says.

NetSI Sport has even started to detect, to continue the metaphor, accents of play between teams. Torricelli says that the most varied play styles, analyzed this way, are found in the English Premier League. Each team “speaks” in identifiably different patterns. In Italy and Germany, those teams play with more nationally coherent rhythms.

“Network science can help you get an idea of the synergy of a team and how the collective efforts” build into something new, Torricelli continues.

Passing the ball

Their work isn’t all theoretical, Klein points out, as the NetSI Sport group reaches out to teams at every level to understand how they gather and employ data in their decision-making.

Often, Klein says, coaches prefer to operate from places of intuition, “still data driven, but less directly applied from research and more based on their experience.” Klein hopes that NetSI Sport will become an asset both for on-the-turf action and for “pie in the sky ideas.”

Klein says that he is also excited for the opportunity to teach a new class that has sprung out of NetSI Sport work. The class will feature “little vignettes of the ways that data is analyzed in sports,” he says, “including the famous Moneyball paper.”

“You can learn so much about statistics and data science and network science and complex system science and the quantitative study of any system in general, trojan-horsed through sports,” he continues. The class will also cover games like chess and e-sports.

March Madness will also be on, Klein notes with a grin, near the end of the semester, and students will have the opportunity to employ their “favorite random forest model,” a kind of machine learning, to try to predict how the brackets will shake out.

But about 40% of the course will tie in directly to the NetSI Sport group’s work. “What if you had this event representation of a soccer match? What could you do with it?” Klein asks.

Northeastern Global News, in your inbox.

Sign up for NGN’s daily newsletter for news, discovery and analysis from around the world.