This post was originally published on here

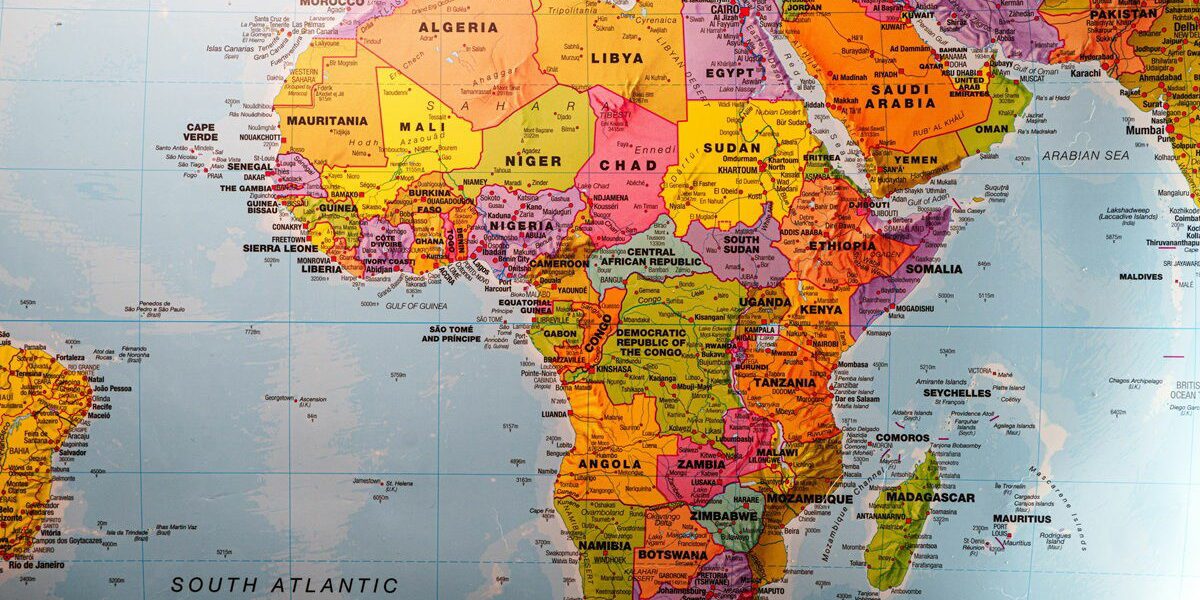

Africa, where slow tectonic forces are gradually reshaping the continent over millions of years

Credit : Rokas Tenys, Shutterstock

It doesn’t look dramatic. There are no collapsing cities, no continents suddenly falling into the sea. And yet, beneath parts of East Africa, something extraordinary is unfolding.

Africa is slowly splitting in two. Not tomorrow. Not in our lifetime. But right now, in geological terms, the process is already well underway.

Scientists have been tracking this gradual separation for years. What they are seeing isn’t a disaster movie scenario, but a slow, relentless reshaping of the planet – the same kind of movement that once created entire oceans.

The ground is moving, even if we don’t feel it

From the outside, continents seem solid and permanent. But Earth doesn’t work that way. Beneath the surface, massive tectonic plates are constantly shifting, pushed by heat and pressure deep inside the planet.

In East Africa, those forces are especially visible.

The region sits on one of the world’s most active geological fault systems: the East African Rift. It stretches thousands of kilometres, from Mozambique all the way to the Red Sea, cutting through countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. The process began millions of years ago. What makes it remarkable today is that scientists can observe it happening on land – something that is rare in geological terms.

At the centre of it all is the Afar region in Ethiopia, where three tectonic plates meet: the Nubian, Somali and Arabian plates. Instead of crashing into each other, they are slowly drifting apart.

The signs are already there. The land fractures. Volcanoes remain active. Lakes expand. Earthquakes occur regularly. None of this is sudden – but all of it points in the same direction.

East Africa is slowly breaking away

Thanks to modern GPS technology, researchers can now measure continental movement with astonishing precision. And the data confirms what geologists long suspected.

The Somali Plate, which includes much of the Horn of Africa, is moving away from the rest of the continent by around six millimetres a year. That may sound insignificant. Over millions of years, it’s anything but.

Studies from institutions such as MIT and the University of Rochester show that this gradual motion is pulling East Africa further and further from the Nubian Plate. Eventually, the landmass could separate entirely.

This has happened before.

A 2014 study published in the journal Tectonics compared the current situation in East Africa with the ancient breakup of Africa and South America, which led to the formation of the Atlantic Ocean. The process was slow, complex and stretched over tens of millions of years — just like what scientists are seeing today.

In other words, East Africa appears to be following a familiar geological script.

Could a new ocean really form?

The short answer is yes – but not anytime soon.

According to geological models cited by IFLScience, if the rifting continues at its current pace, seawater could eventually flood the widening裂 in the Earth’s crust. Over five to ten million years, a new ocean basin could emerge where the Rift Valley lies today.

If that happens, countries such as Somalia, Djibouti and parts of Kenya would become geologically separate from the rest of Africa, forming a new landmass altogether.

This kind of continental breakup doesn’t just change maps. It alters climates, redirects water systems and reshapes ecosystems. When continents separate, species become isolated, and evolution takes new paths – something that has happened repeatedly throughout Earth’s history.

For now, however, the changes remain subtle. A deeper lake. A new fissure. A volcanic tremor. Easy to ignore in daily life, but significant when seen as part of a much bigger picture.

Africa is not ‘cracking open’ overnight. It is slowly, patiently changing, following the same natural forces that have shaped the planet for billions of years.

And while humans may never live to see the final result, the process itself is already written into the landscape – quietly, relentlessly, and entirely on Earth’s own timetable.