This post was originally published on here

In a groundbreaking first, researchers have 3D-printed microscopic structures, including a 10-micrometer elephant, inside the cytoplasm of living cells. The technique, which uses a biocompatible photoresist and precise laser-based polymerization, allows cells to not only survive the process but also divide, passing the printed object to daughter cells.

This new method could transform the way scientists interact with and study individual cells. By enabling the construction of micro-devices inside cells, it bypasses previous limitations of particle ingestion and opens access to a broader range of cell types.

The development, led by physicist Matjaž Humar at the Jožef Stefan Institute in Slovenia, represents a leap forward in intracellular bioengineering. Unlike prior approaches that relied on cells swallowing particles via phagocytosis, a method only available to specific cell types, this technology injects material directly into the cell’s interior and prints on-site, with minimal structural disruption. While the process still presents challenges related to cell viability, it offers a far more versatile and controllable platform.

Printing From the Inside Out

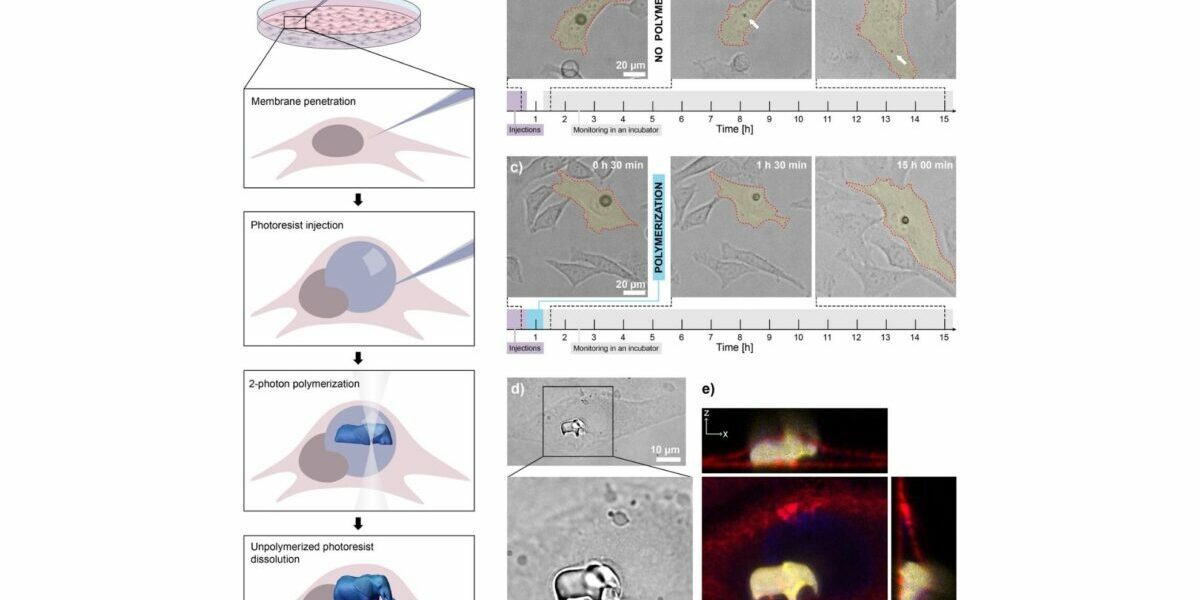

At the core of the process is a laser-based technique known as two-photon polymerization. Scientists begin by injecting a droplet of light-sensitive resin (known as a photoresist) into a cell. Once inside, a highly focused femtosecond laser selectively hardens the material along a programmed 3D path, layer by layer, forming a complete structure within the cytoplasm. Any remaining photoresist gradually dissolves without harming the cell.

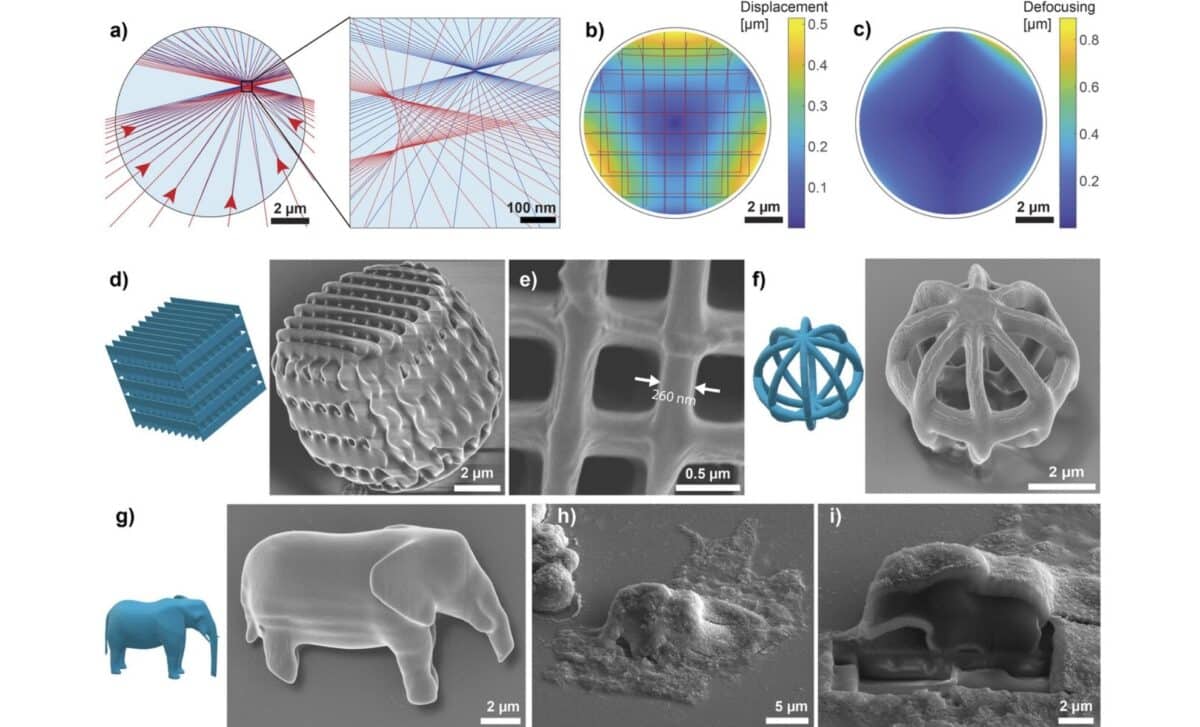

According to Advanced Materials, researchers used this method to produce complex shapes like geometric patterns, layered barcodes, and even diffraction gratings. The elephant model, measuring just 10 micrometers wide, was used as a symbolic demonstration of how much detail this method can achieve. Humar’s team relied on a commercial 3D printer system (Photonic Professional GT2 by Nanoscribe) to produce the structures, which included optical components and potential sensing devices.

Unlike previous methods, this approach doesn’t trap the structure in a vesicle or membrane. The microstructure is left floating in the cytosol, integrated directly into the cell’s environment. As reported by Science News, this provides scientists with a clearer and more direct interaction with internal cellular processes.

Testing the Limits of Life and Structure

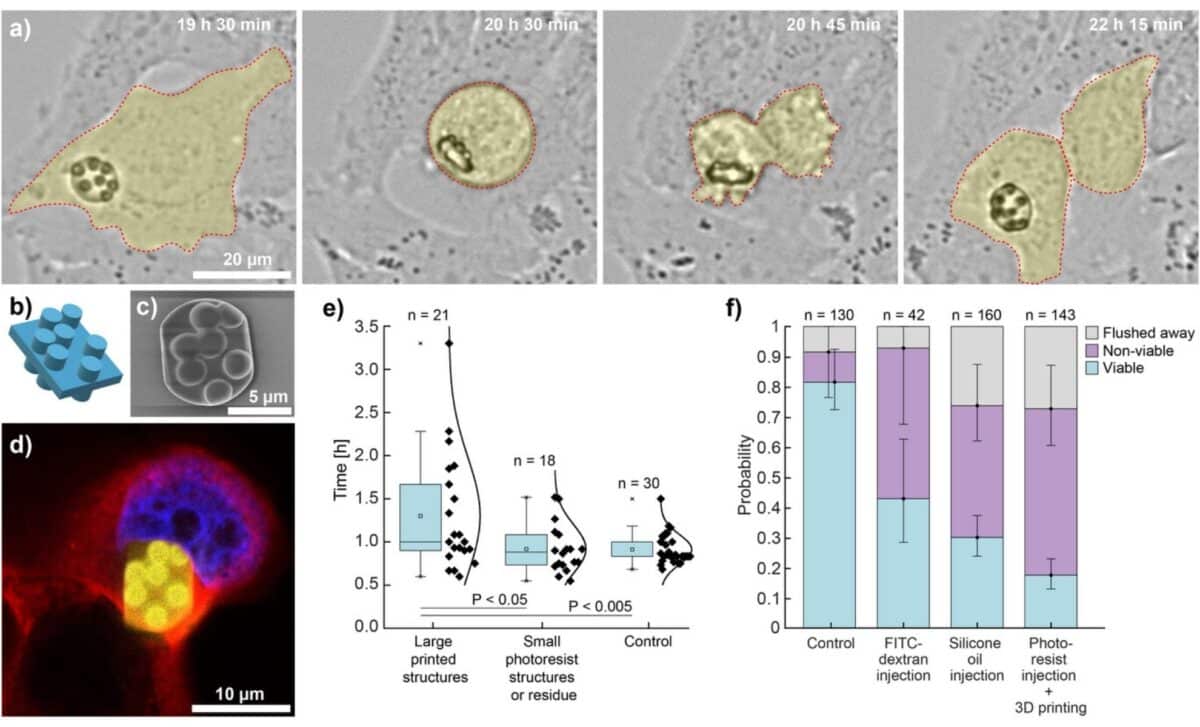

To assess the impact of the technique on cell survival, researchers conducted a 24-hour viability study using HeLa cells. According to results shared in the arXiv preprint, approximately 55% of cells with printed structures remained viable after one day. Cells injected with inert silicone oil had a survival rate of 44%, while buffer-injected cells reached 50%. Even the control group (cells not injected at all) showed a 10% mortality rate, likely due to prolonged handling.

While cell death was notable, it was primarily attributed to membrane damage during the injection process, rather than the 3D printing itself. Many of the surviving cells continued normal activities. One cell was even observed undergoing division and passing its internal 3D-printed logo (shaped like the Jožef Stefan Institute emblem) to one of its daughter cells.

Confocal imaging confirmed that internal components like the nucleus and actin filaments adapted to accommodate the foreign objects. The printed structures were stiff, did not deform, and were often well-integrated into the cell’s architecture. In tests of print quality, features as small as 260 nanometers were produced with minimal distortion, comparable to structures printed outside of cells.

Miniature Machines With Real-World Potential

Beyond their novelty, the printed microstructures were designed with future functionality in mind. Among the most promising applications is intracellular barcoding: by stacking four layers of 4×4 cylindrical grids, researchers created barcodes that can store 61 bits of data, enough to assign a unique code to more cells than there are in the human body. These structures, unlike random spectral barcodes, allow for predefined tagging of individual cells.

In another demonstration, scientists created diffraction gratings, tiny optical devices that, when illuminated, project a light pattern that changes with cell orientation. This allows remote tracking of cellular rotation in all three dimensions.

Researchers also managed to print whispering-gallery mode microlasers, using a higher-index photoresist doped with fluorescent dye. These tiny resonators emitted light when excited, producing distinct optical signatures. Although the photoresist used in this case was more toxic (80% of the treated cells died) the result shows that functional optical devices can be constructed entirely within living cells.

The ability to embed such tools directly into the cytoplasm, not just in specialized cells, but across a wide range, offers scientists unprecedented access to the cell interior. According to the research team, the next steps could include printing mechanical levers, barriers, or cages that physically interact with organelles, or even developing photoresists capable of distributing across the cytosol for complete internal control.