This post was originally published on here

The protein called intelectin-2 plays another important role by reinforcing the protective mucus layer that lines the digestive system.

The body’s mucosal linings contain a range of protective molecules that help stop microbes from triggering inflammation or infection. One important group of these defenders is lectins, which identify microbes and other cells by attaching to sugars on their surfaces.

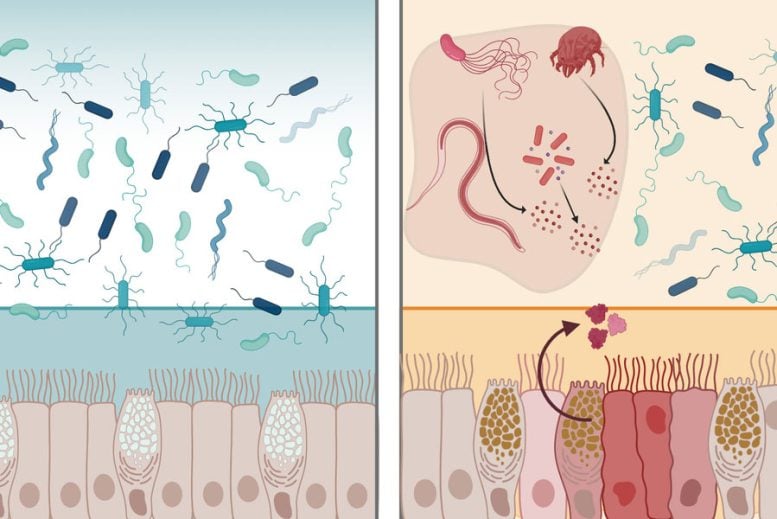

MIT researchers report that one lectin can act against many types of bacteria in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The protein, called intelectin-2, latches onto sugars on bacterial membranes, which helps trap the microbes and slows their growth. It also links together components of mucus, a step that can reinforce the mucus barrier.

“What’s remarkable is that intelectin-2 operates in two complementary ways. It helps stabilize the mucus layer, and if that barrier is compromised, it can directly neutralize or restrain bacteria that begin to escape,” says Laura Kiessling, the Novartis Professor of Chemistry at MIT and the senior author of the study.

Because intelectin-2 appears to work broadly against gut bacteria, the researchers say it could be developed into a therapeutic approach. They also suggest it might be used to bolster the mucus barrier in conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease.

Amanda Dugan, a former MIT research scientist, and Deepsing Syangtan PhD ’24 are the lead authors of the paper, which was recently published in Nature Communications.

A multifunctional protein

Current evidence suggests that the human genome encodes more than 200 lectins — carbohydrate-binding proteins that play a variety of roles in the immune system and in communication between cells. Kiessling’s lab, which has been exploring lectin-carbohydrate interactions, recently became interested in a family of lectins called intelectins. In humans, this family includes two lectins, intelectin-1 and intelectin-2.

Those two proteins have very similar structures, but intelectin-1 is distinctive in that it only binds to carbohydrates found in bacteria and other microbes. About 10 years ago, Kiessling and her colleagues were able to discover intelectin-1’s structure, but its functions are still not fully understood.

At that time, scientists hypothesized that intelectin-2 might play a role in immune defense, but there hadn’t been many studies to support that idea. Dugan, then a postdoc in Kiessling’s lab, set out to learn more about intelectin-2.

Linking mucus and microbes

In humans, intelectin-2 is produced at steady levels by Paneth cells in the small intestine, but in mice, its expression from mucus-producing Goblet cells appears to be triggered by inflammation and certain types of parasitic infection.

In the new study, the researchers found that both human and mouse intelectin-2 bind to a sugar molecule called galactose. This sugar is commonly found in molecules called mucins that make up mucus. When intelectin-2 binds to these mucins, it helps to strengthen the mucus barrier, the researchers found.

Galactose is also found in carbohydrates displayed on the surfaces of some bacterial cells. The researchers showed that intelectin-2 can bind to microbes that display these sugars, including many pathogens that cause GI infections.

The researchers also found that over time, these trapped microbes eventually disintegrate, suggesting that the protein is able to kill them by disrupting their cell membranes. This antimicrobial activity appears to affect a wide range of bacteria, including some that are resistant to traditional antibiotics.

These dual functions help to protect the lining of the GI tract from infection, the researchers believe.

“Intelectin-2 first reinforces the mucus barrier itself, and then if that barrier is breached, it can control the bacteria and restrict their growth,” Kiessling says.

Fighting off infection

In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, intelectin-2 levels can become abnormally high or low. Low levels could contribute to degradation of the mucus barrier, while high levels could kill off too many beneficial bacteria that normally live in the gut. Finding ways to restore the correct levels of intelectin-2 could be beneficial for those patients, the researchers say.

“Our findings show just how critical it is to stabilize the mucus barrier. Looking ahead, we can imagine exploiting lectin properties to design proteins that actively reinforce that protective layer,” Kiessling says.

Because intelectin-2 can neutralize or eliminate pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae, which are often difficult to treat with antibiotics, it could potentially be adapted as an antimicrobial agent.

“Harnessing human lectins as tools to combat antimicrobial resistance opens up a fundamentally new strategy that draws on our own innate immune defenses,” Kiessling says. “Taking advantage of proteins that the body already uses to protect itself against pathogens is compelling and a direction that we are pursuing.”

Reference: “Intelectin-2 is a broad-spectrum antimicrobial lectin” by Amanda E. Dugan, Deepsing Syangtan, Eric B. Nonnecke, Rajeev S. Chorghade, Amanda L. Peiffer, Jenny J. Yao, Jessica Ille-Bunn, Dallis Sergio, Gleb Pishchany, Catherine Dhennezel, Hera Vlamakis, Sunhee Bae, Sheila Johnson, Chariesse Ellis, Soumi Ghosh, Jill W. Alty, Carolyn E. Barnes, Miri Krupkin, Gerardo Cárcamo-Oyarce, Katharina Ribbeck, Ramnik J. Xavier, Charles L. Bevins and Laura L. Kiessling, 13 January 2026, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67099-4

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health Glycoscience Common Fund, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Science Foundation.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.