This post was originally published on here

Scientists have uncovered a new way embryonic cells divide when conventional mechanisms fail.

Cell division underpins all forms of life, but scientists have long struggled to explain how this process unfolds during the earliest stages of embryonic development, especially in egg-laying species. Researchers from the Brugués group at the Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life (PoL) at TUD Dresden University of Technology have now identified an unexpected mechanism that allows early embryonic cells to divide without forming a complete contractile ring, a structure traditionally thought to be indispensable.

Their results, reported in Nature, overturn conventional textbook explanations of cell division. The study shows that elements of the cytoskeleton work together with the physical properties of the cell interior (or cytoplasm) to drive division through what the researchers describe as a ratchet-like process.

Rethinking the Contractile Ring Model

In many organisms, cell division relies on a contractile ring made of the protein actin that forms around the middle of the cell. As this ring tightens, much like a drawstring, it squeezes the cell until it splits into two separate cells. While this purse-string mechanism is common, it does not apply to all species.

Animals with extremely large embryonic cells, including sharks, platypuses, birds, and reptiles, present a special challenge. Their cells contain massive yolk sacs and are so large that the actin ring cannot fully close, making the standard division model ineffective.

For years, how these oversized cells manage to divide remained unresolved.

“With such a large yolk in the embryonic cell, there is a geometric constraint. How does a contractile band, with loose ends, remain stable and generate enough force to divide these huge cells?” asked Alison Kickuth, a recently graduated PhD student from the Brugués group at the Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life (PoL) and lead author of the study. Their experiments, published in a seminal new study in Nature, have found an answer to this question.

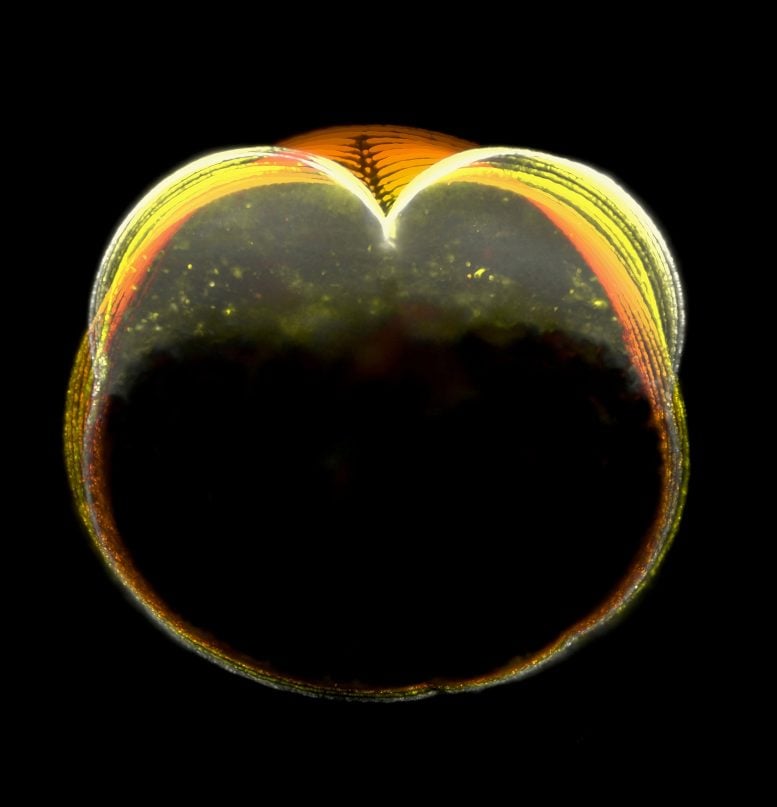

To uncover the mechanism, the researchers turned to zebrafish embryos, which divide quickly and also contain large, yolk-rich cells during early development. Using a laser to cut through the actin band with high precision, Kickuth found that the band continued to move inward even after being severed. This behavior indicated that the band was supported by multiple anchoring points along its length rather than relying solely on its ends.

The Role of Microtubules in Stabilization

In addition, it seemed that microtubules, another essential part of the cytoskeleton, appeared to bend and splay in response to the laser cuts, and had a critical role in stabilizing the band during contraction. To clarify the role of microtubules in this process, the authors disrupted them in two separate experiments: by chemically inducing depolymerization (effectively stopping new microtubules from forming), and by physically disrupting them using an obstacle, in the form of a microscopic oil droplet.

Without microtubules, the actin band collapsed, proving that microtubules are essential for holding the band in place, and provided both mechanical support and signalling during its formation.

Changes in the cytoskeleton are known to happen in other species as cell cycles progress. Importantly, the cell cycle is separated into distinct phases of activity; a mitotic phase (M-phase), where the DNA is divided, and an interphase, where a typical cell grows and replicates its DNA. After DNA has been divided, large structures made of microtubules called asters grow to span the entire cytoplasm.

These asters are essential during interphase for deciding where the actin band will form and start contracting, marking the future cleavage plane. Given that microtubules are known to stiffen the cytoplasm in various cellular contexts, the authors sought to explore if asters would contribute to stiffening to help anchor the actin band. To investigate, the authors employed magnetic beads and observed their displacement under magnetic forces. These experiments allowed the scientists to measure changes in cytoplasmic stiffness during cell cycle stages.

They found that the cytoplasm becomes stiffer during interphase, acting as a scaffold to stabilize the actin band. In turn, it becomes more fluid during M-phase, allowing the band’s ingression between the two future cells. These dynamic changes in stiffening and fluidization play a key role in the division process.

A Mechanical Ratchet for Division

Only one question remained: How did the band remain stable throughout M-phase despite the cytoplasm becoming more fluid-like? By imaging the ends of the actin band over time, the team observed that although the band is unstable during M-phase while contracting, it did not collapse fully. Instead, this retraction is “rescued” due to the fast cell cycles in these early stages.

In the following interphase, when the cytoplasm stiffens again due to the asters reappearing, the band becomes re-stabilized. Then, the actin band continued ingressing during the next fluid-phase. These cycles of instability during M-phase and stabilization during interphase repeated over several cell cycles until division was complete. This alternating pattern acts like a ‘mechanical ratchet’, driving cell division without needing a fully-formed contractile ring. In this case, division is possible through the alternating material properties of the cytoplasm, and takes place over multiple cell cycles instead of just one.

“The temporal ratchet mechanism fundamentally alters our view of how cytokinesis works,” emphasized Jan Brugués, corresponding author of the study. This finding provided an effective solution for early cell divisions in cells that were too large for conventional cell division, and have rapid cell cycles.

“Zebrafish are a fascinating case, as cytoplasmic division in their embryonic cells is inherently unstable. To overcome this instability, their cells divide rapidly, allowing ingression of the band over several cell cycles by alternating between stability and fluidization until division is complete,” highlighted Alison regarding this finding. This discovery represents a novel paradigm for understanding cell division in large embryonic cells and may apply broadly across species with yolk-rich embryos.

Additionally, this study highlights temporal control of material properties in the cytoplasm as an important contributor to cellular processes, a role that may be expanded in future studies. Understanding these mechanisms will open new perspectives for studying development in different species.

Reference: “A mechanical ratchet drives unilateral cytokinesis” by Alison Kickuth, Urša Uršič, Michael F. Staddon and Jan Brugués, 7 January 2026, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09915-x

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.