This post was originally published on here

Scientists have confirmed what many pet owners already know to be true – the death of a pet can hurt just as much as losing a family member.

In their study, the team from Maynooth University surveyed almost 1,000 Brits about different bereavements.

The results revealed that more than one in five Brits think the death of a pet is more distressing than the death of a human.

Based on the findings, the experts believe that a pet’s death can lead to ‘prolonged grief disorder’, or PGD.

This psychiatric disorder was formally classified by the World Health Organisation in 2018, and is characterised by elevated levels of bereavement–related distress.

However, it can currrently only be diagnosed following the death of a person.

‘People can experience clinically significant levels of PGD following the death of a pet,’ the researchers explained in their study.

‘PGD symptoms manifest in the same way regardless of the species of the deceased.’

Whether it’s through natural causes, old age, or euthanasia, the loss of a pet can be devastating for owners.

However, until now, how pet bereavement compares to the death of a human has remained unclear.

To get to the bottom of it, Dr Philip Hyland, a professor in the Department of Psychology at Maynooth University, enlisted 975 Brits to talk about their experiences with different bereavements.

The results revealed that almost one third (32.6 per cent) had experienced the death of a pet, while almost all participants had experienced the death of a human.

However, 21 per cent of these people chose the death of their pet as the most distressing.

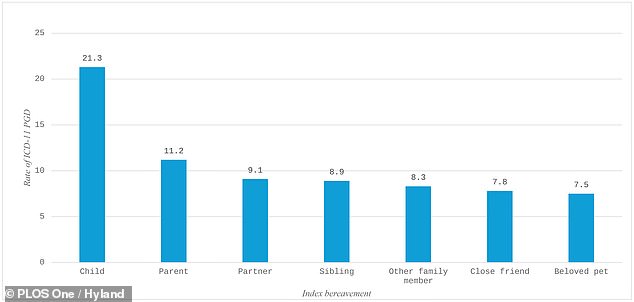

Following the death of a pet, 7.5 per cent of the participants met the diagnostic requirements PGD.

This is very similar to the rates for the death of a close friend (7.8 per cent), a family member such as a grandparent, cousin, aunt/uncle (8.3 per cent), a sibling (8.9 per cent), and even a partner (9.1 per cent).

Only the death of a parent (11.2 per cent) and the death of a child (21.3 per cent) were markedly higher.

Based on the findings, Dr Hyland is calling for the criteria for PGD diagnosis to be extended to include the death of a pet.

‘It is not clear why the death of a pet was excluded from the bereavement criterion for PGD,’ he explained in the study, published in PLOS One.

‘It is possible that the controversial nature of the diagnosis meant that the different working groups were reluctant to acknowledge that pet loss can lead to PGD for fear of being viewed as unserious.

‘Another reason may be that the members of these working groups sincerely believed that there is something uniquely special about human beings’ attachments to other human beings.

‘Whatever the reason, it is important to test if people bereaved by the death of a pet can experience disordered grief in the manner it is now described in the psychiatric nomenclature.’