This post was originally published on here

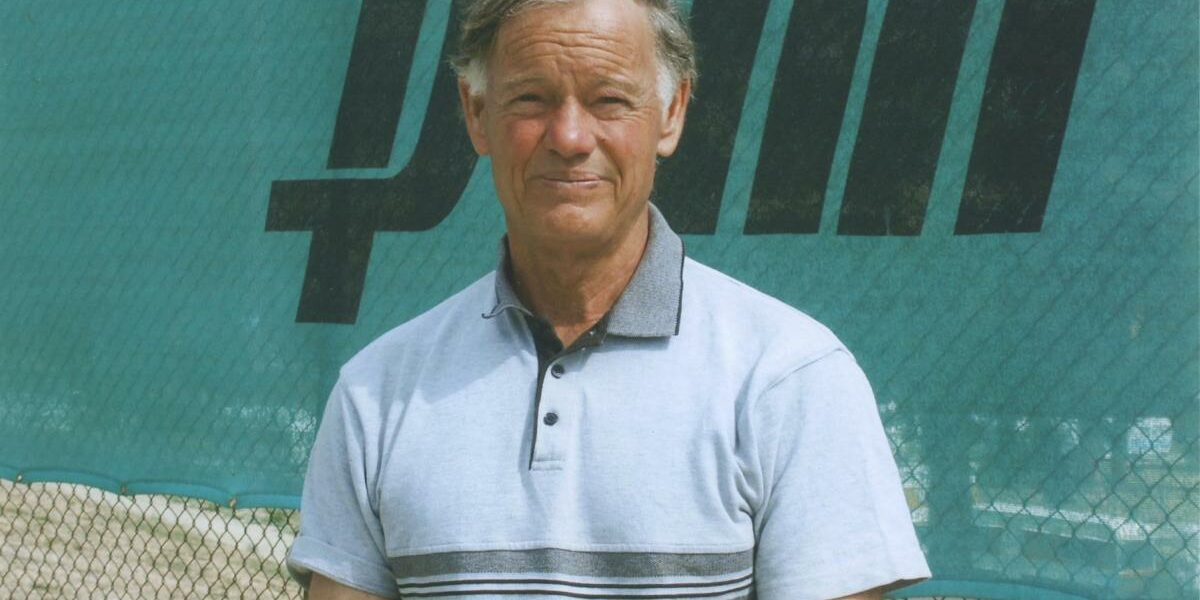

From first-year students to Nobel Prize laureates, the name David Anson Buckingham was held in high esteem by scientists across the globe.

Wherever the University of Otago emeritus professor of chemistry went, he left big footprints in the lives of his students, fellow staff and even people he had never met.

Prof Buckingham was born in Dunedin, on March 13, 1936, to Alfred and Aline Buckingham, of Rangiora.

He was one of the first babies in New Zealand to be born by Caesarean section, which was a new procedure at the time, which was the reason he was born in Dunedin Hospital.

He grew up in Rangiora, did his schooling there and with no television during his childhood, there was a different pace to life.

Entertainment came in the form of sport and music. Prof Buckingham learnt violin, and on Sunday afternoons, friends would come around to play their instruments with him and his family.

He loved to listen to music recordings, and found inspiration in the performances of overseas opera companies and orchestras.

From a young age, he was very musical, academically able and very sporty — particularly when it came to rugby, tennis and cricket.

During his time at Rangiora District High School, his character and leadership led to his appointment as head boy and captain of the first XV rugby and first XI cricket teams.

He went on to attend the University of Canterbury, where he gained a bachelor of science and a master of science (honours) in chemistry.

He continued with his music and tennis during his tertiary studies, and it was while playing tennis he met his future wife, Marion.

As a master of romantic improvisation, he intentionally hit a ball on to the court she was playing on and, as a true gentleman, he apologised to her for interrupting her game while retrieving his ball. The rest was history.

They married, and soon after, moved to Canberra, Australia, where Prof Buckingham did a PhD and conducted research at Australian National University, under Frank Dwyer — the best inorganic chemist in Australia at the time.

He also continued to play violin and viola for the Canberra Symphony Orchestra.

By the time he completed his PhD in chemistry in 1962, his reputation in chemistry was spreading quickly, and soon after, he began postdoctoral research at Brown University, Stanford University and the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill) with Prof Jim Collman, one of the top young chemists in the United States.

He spent 18 months in the United States before being appointed to an assistant professorship position at Brown University, an Ivy League university in Rhode Island.

But the professorship was not for him, and he returned to Australian National University in 1965, where he began working with another prominent inorganic chemist, Alan Sargeson.

The duo went on to make massive advances in inorganic chemistry in Australia, collaborating in the areas of inorganic and biomimetic chemistry, and their investigations received international recognition.

In the 1970s, Prof Buckingham, Marion and their young family moved to Dunedin when he was appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Otago.

An Otago Daily Times article at the time described him as a scientist “with an international reputation as one of the best chemical scientists in his field”.

He was a recognised expert in “inorganic reaction mechanism” and the winner of international awards, including the acclaimed Corday-Morgan Medal and a prize from the Chemical Society, in London.

Despite his busy teaching schedules, he continued to make major research advancements at Otago.

Unlike typical academics, Prof Buckingham would not spend long hours in his office writing papers and lectures. Instead, he would spend most of his time in his lab — 5S7 — getting his hands dirty.

It was his favourite place in the world, and his students and fellow staff always noted the infectious look of enthusiasm on his face every time he entered that room. He would sail into the lab with a bright smile on his face and ask everyone how their day was going, before listening to their responses with interest and intent.

Former student and Auckland University of Technology chemistry professor Allan Blackman said Prof Buckingham was always looking over his students’ shoulders, showing them how to do stuff and making sure they did it correctly.

He also showed them what not to do. On one infamous occasion, he wanted to carry out a chemical reaction involving 100% perchloric acid.

“The colourless liquid is only sold as a 70% solution in water, because at 100%, it’s highly explosive.

“So he decided to make some 100% perchloric acid.

“He siphoned off about 10ml of it for his experiment, but it blew up and destroyed the fume hood in which he was working.”

The incident left Prof Buckingham bleeding and he was taken to Dunedin Hospital. Because he had made a whole batch of the highly explosive chemical, the bomb squad came in and disposed of the rest of it.

A highlight each year would be his end-of-year potluck dinner for his PhD students.

Many of his students and fellow staff said he had had a meaningful impact on their lives. By virtue of being taught by Prof Buckingham, many of his students were able to go on to do postdoctoral study in the United States with some of the world’s foremost chemists there.

He was so well known for his quality work, that Nobel laureates in chemistry were known to sing his praises.

When Prof Buckingham took early retirement in 1995, at the age of 58, it surprised many of his peers because he still had so much to give to chemistry.

But the Royal Society of New Zealand, Royal Australian Chemical Institute and New Zealand Institute of Chemistry fellow simply said he had achieved all that he wanted to.

He continued to work part-time at Otago until 2003, when he published his final paper.

His first paper was published in 1963, bringing his total number of career publications to 209 — many of which are still being cited today.

Prof Buckingham’s academic legacy lives on in the students he mentored, the colleagues he worked with and the superb papers he published.

His retirement may have seemed premature to others, but for Prof Buckingham, it gave him an opportunity to spend more time on one of his other passions — tennis. During his academic career in Dunedin, he continued to be very active in tennis, by joining the Cosy Dell Tennis Club, where he became president and life member, and becoming president of Otago Tennis.

Following his retirement, he moved to Wānaka and, not surprisingly, he brought some much-needed enthusiasm to the local tennis club and helped get it up and running again.

He became president, club captain and “chief bottle washer”, gathering many people around him with his can-do attitude. For his services to the club, he was made a life member.

He was the driving force behind the creation of a top-class facility with top-class coaching, all the while continuing to play veterans tennis and winning the odd competition here and there.

He loved every minute of it. If he wasn’t at home, he was at the tennis club.

He also loved to go tramping with close friends on tracks around Fiordland and Mount Aspiring National Park.

In his latter years, Prof Buckingham developed dementia and moved to a rest-home in Milton.

Even while he was there, he continued to share his vast science knowledge with fellow residents and staff. He even taught one staff member the periodic table of elements.

He remained a teacher until the very end.

A letter from his nurse in Milton, said: “He is a kind, caring and intelligent man, who loves engaging in conversation about physics, astronomy and academia.

“It has been an absolute privilege to care for him.

“He is truly someone who makes the world a better place.”

For his final days, he returned to his beloved Wānaka to be among family and friends.

At his memorial service, he was remembered as a kind, good-humoured, vivacious man, always with an infectious smile, a warm word of encouragement and a positive attitude to everything he turned to, and gained a genuine and tremendous respect from his friends and academic peers.

He died on September 11, aged 89. He is survived by his son Nigel and daughter-in-law Lee, son Mark and daughter-in-law Karen, daughter Anna and his grandchildren. — John Lewis

DAVID ANSON BUCKINGHAM

Scientist