This post was originally published on here

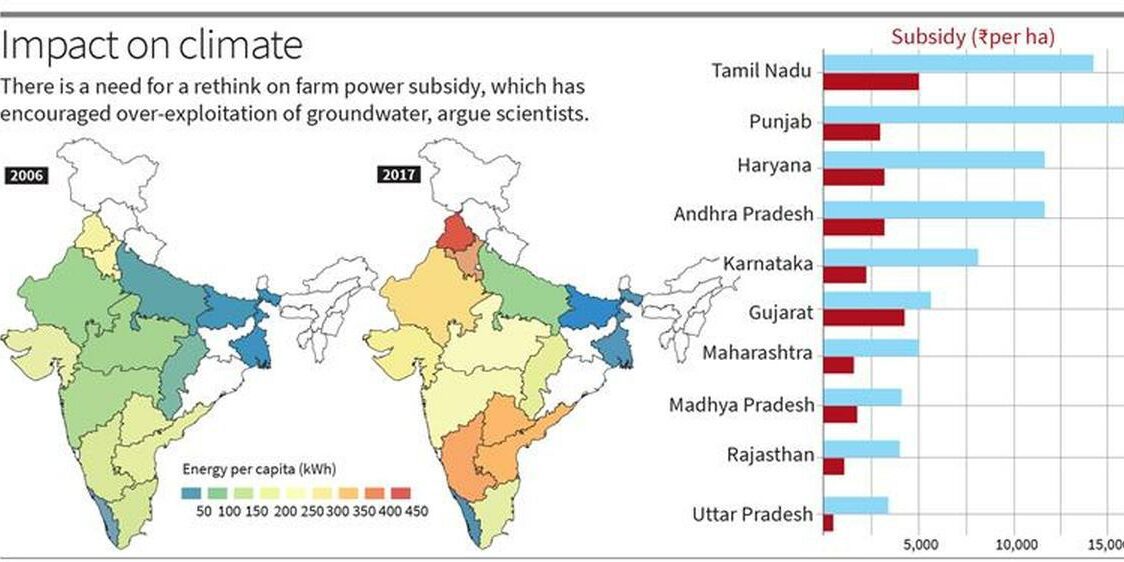

The free electricity driving millions of farm pumps is now responsible for an estimated 100 million tonnes of carbon emissions every year, while groundwater — once thought inexhaustible in many regions — is rapidly vanishing. Policies designed decades ago to support farmers are inadvertently deepening inequalities between States and communities, warn scientists.

Researchers from some of the country’s leading public institutions are now sounding the alarm. They are urging both the Centre and State governments to urgently revisit the farm power subsidy (FPS) and shift India toward a more climate‑resilient model of irrigation and food production.

The FPS — underpinned by a 72% coal-based energy requirement — has become one of India’s most carbon‑intensive public support mechanisms. Hence, they call for a fundamental rethink of groundwater‑based irrigation and a broader shift in cropping and dietary patterns to reduce emissions and build resilience.

They also advocate reviving India’s long tradition of coarse cereal consumption through economic incentives, assured procurement under the minimum support price (MSP) and focused promotion to re-establish millets as staple foods. Since the mid‑2000s, after the widespread rollout of free power subsidies, CO₂‑equivalent emissions have been rising by 5.77 million tonnes annually, now exceeding 100 million tonnes, they noted.

They argue that even highly subsidised rice and wheat supplied through the public distribution system (PDS) to more than 800 million people could gradually be replaced by regionally appropriate crops — rice in the east, and coarse cereal millets in the west and south — offering greater economic and ecological gains.

Farmers, they say, should be encouraged to adopt traditional rain‑fed systems or switch to crops suited to regional water availability without compromising food security or income. This transition can be supported through financial incentives for water and energy savings, along with compensation for crop losses triggered by climate extremes — measures they deem vital for meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“We suggest repurposing agricultural policies, without compromising farmers’ income, for efficient management of energy and water,” said Director of the CSIR–North East Institute of Science and Technology (Jorhat), and former Director of the CSIR–National Geophysical Research Institute, Virendra M. Tiwari.

Mr. Tiwari — along with scientists Dileep K. Panda and Arjamadutta Sarangi of the ICAR–Indian Institute of Water Management (Bhubaneswar), Sunil K. Ambast of the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), Ministry of Jal Shakti, and Rajbir Singh of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), New Delhi — has authored a study titled “Envisioning Farm Power Subsidy for Groundwater Irrigation in India for Attaining SDGs”, published in the international journal Earth’s Future.

The study notes that while FPS and loan waivers are often introduced to address inequality, the outcomes tend instead to widen disparities and compromise multiple SDGs — particularly SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation), SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), and SDG 13 (climate action).

Given the multi‑dimensional nature of these challenges and their overlap across SDGs, the authors call for an objective assessment of policy synergies and trade‑offs, taking into account the experiences of both farmers and consumers. Aligning interventions with SDG 12, they suggest, could significantly mitigate the current crisis.

The study underscores the need to preserve natural landscapes and highlights how prevailing agricultural practices are misaligned with contemporary climate realities. Strengthening local economies through green climate finance for carbon capture and storage, would be more sustainable than continuing with irrigation‑driven agricultural models of the past, argue scientists.

Highlighting the nutritional and environmental advantages of coarse cereals — once staple foods among poorer and tribal communities — the authors say the FPS has encouraged a simplification and intensification of food production that has widened income disparities across states and districts.

States implementing FPS, including those facing acute water scarcity, continue to cultivate water‑intensive crops for economic returns. Meanwhile, States suffering from economic water scarcity — where energy access is insufficient — cannot fully harness groundwater resources, resulting in low farm incomes, labour migration, and widening gender wage gaps.

Despite fertile soils, prolific aquifers, and favourable hydroclimatic conditions in the Indo‑Gangetic Plains, States such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal have lagged behind more prosperous southern and western States. Their poor access to affordable energy has hindered investment in borewells and other inputs necessary for commercially viable agriculture. In contrast, arid and hard‑rock dominated regions in the south and west have expanded agricultural production despite hydrogeological challenges, the study notes.

The researchers emphasise that technologies already exist to boost irrigation efficiency and conserve water — including micro‑irrigation and improved water‑management approaches to arrest groundwater depletion. These efforts are reinforced by programmes such as the ‘Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana’ (PMKSY), which promotes micro‑irrigation, and the World Bank‑supported ‘Atal Bhujal Yojana’ to strengthen groundwater management.

While subsidised rice and wheat under PDS meet basic calorie needs, this has come at the expense of the health and environmental benefits offered by nutrient‑rich, low‑water‑requiring millets. With urban consumers increasingly embracing millets, the scientists say India must revive its millet‑based dietary traditions through economic incentives, assured MSP procurement and targeted promotion.

Published – January 17, 2026 12:02 am IST

Email

SEE ALL

Remove