This post was originally published on here

Artificial sweeteners were supposed to make sugary foods and beverages healthier, but today, some of the most popular zero-calorie substitutes are raising new concerns.

An up-and-coming natural alternative could one day be produced on a much grander scale, using enzymes from slime mold.

The natural sugar is called tagatose, and not only does it taste 92 percent as sweet as sucrose (or table sugar), but it also packs only around a third of the calories.

What’s particularly exciting about it is that it does not spike insulin levels like sucrose or high-intensity artificial sweeteners – making it a potentially attractive option for those with diabetes or blood glucose issues.

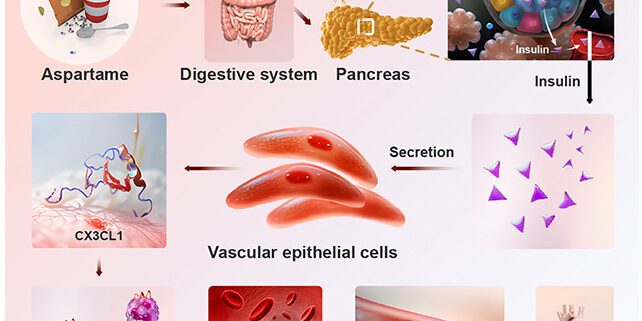

Related: Even Low Doses of Aspartame Could Have Alarming Health Effects, Study Finds

Researchers at Tufts University, in partnership with biotechnology companies Manus Bio (US) and Kcat Enzymatic (India), have now led a proof-of-principle study to show that tagatose can be produced sustainably and efficiently – a challenge that has so far held the market back.

Tagatose is a rare natural sweetener, found in only small amounts in some dairy products and fruits. It offers a potentially healthier option to sucrose as well as artificial sweeteners, which can both drive strong spikes in insulin.

One key reason that tagatose doesn’t have the same effect is that much of it appears to be fermented in the large intestine. It’s only partially absorbed into the bloodstream via the small intestine.

In the gut, the rare sugar is metabolized in a similar way to the fruit sugar, fructose – meaning those with fructose intolerances may want to steer clear – but tagatose is generally recognized as safe for consumption by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Tagatose is also considered ‘tooth-friendly’, and it may even have prebiotic perks for the oral microbiome. Unlike sucrose, which feeds certain bacteria in the mouth that contribute to tooth decay, initial research suggests that tagatose limits the growth of harmful oral microbes.

Another big perk is that tagatose can be baked into foods, unlike many other high-intensity sweetener substitutes.

The potential is there, but so far, the tagatose market has been constrained by limited production.

“There are established processes to produce tagatose, but they are inefficient and expensive,” explains biological engineer Nik Nair from Tufts.

“We developed a way to produce tagatose by engineering the bacteria Escherichia coli to work as tiny factories, loaded with the right enzymes to process abundant amounts of glucose into tagatose.”

Specifically, researchers inserted into these bacteria a newly discovered enzyme from slime mold, called galactose-1-phosphate-selective phosphatase (Gal1P). This enzyme converts glucose into galactose, and that product is then turned into tagatose by a second enzyme.

Using this novel sequence, Nair and colleagues have shown that production yields for tagatose can reach up to 95 percent, which is much better than the roughly 40 to 77 percent currently achievable.

“The key innovation in the biosynthesis of tagatose was in finding the slime mold Gal1P enzyme and splicing it into our production bacteria,” says Nair.

“That allowed us to reverse a natural biological pathway that metabolizes galactose to glucose and instead generate galactose from glucose supplied as a feedstock. Tagatose and potentially other rare sugars can be synthesized from that point.”

The team still needs to further optimize their tagatose production line, but they hope their strategy provides a useful framework for future rare-sugar production.

According to some estimates, the tagatose market is expected to reach a value of US$250 million by 2032.

The study was published in Cell Reports Physical Science.