This post was originally published on here

Among all primates, humans are unique for their smooth, nearly hairless skin. That difference has long puzzled evolutionary biologists. Our closest relatives, from chimpanzees to orangutans, remain covered in thick fur, yet somewhere in our past, we began to lose it. The mystery of what turned us into the planet’s “naked ape” is finally gaining clarity as researchers uncover new genetic evidence pointing to silent instructions deep within our DNA.

A Genetic Map Of Lost Fluff

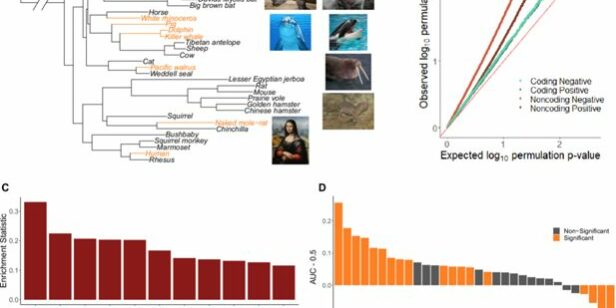

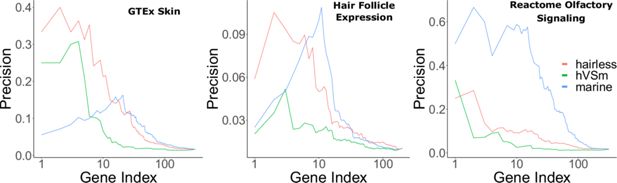

In a groundbreaking cross-species analysis, researchers compared the genomes of 62 mammals to hunt for the roots of hair loss. Their approach revealed something striking: humans still possess all the genes needed for a full coat of fur. What changed were the regulatory elements, the molecular switches that determine whether certain genes are turned on or off. The study’s authors found that these regions evolved at different rates in hairless species, suggesting that the silencing of fur-related genes was a key driver in our evolutionary story.

The team behind the research, including Nathan Clark, Ph.D., Amanda Kowalczyk, Ph.D., and Maria Chikina, Ph.D., designed what they describe as a “first-of-its-kind” genomic analysis. Clark explained the approach: “We have taken the creative approach of using biological diversity to learn about our own genetics,” he said. “This is helping us to pinpoint regions of our genome that contribute to something important to us.”

Their findings, published in eLife, highlight that hair loss across mammals, from dolphins to humans, is not a random occurrence, but the result of convergent evolution, where unrelated species independently develop similar traits through similar genetic pathways.

The Silent Orchestra Behind Hair Growth

Every strand of hair begins with a complex interplay of genes and regulators. The eLife study revealed hundreds of new hair-related regulatory elements, each playing a role in shaping, growing, and maintaining hair. Some of these genes were previously unknown, expanding our understanding of how diverse mammals evolved distinct appearances.

“There are a good number of genes where we don’t know much about them,” said Amanda Kowalczyk, one of the lead researchers. “We think they could have roles in hair growth and maintenance.”

This means that while humans share the same fundamental hair-producing toolkit as other mammals, we’ve turned off much of it, perhaps due to evolutionary pressures linked to temperature regulation, parasite control, or even sexual selection. The presence of these “dormant” genes raises fascinating questions: could they be reactivated, and if so, what would happen? The answers could influence future therapies for hair loss, from male pattern baldness to alopecia.

Convergent Evolution: Nature’s Repeated Experiment

When smooth-skinned species like dolphins, elephants, and humans show similar hair loss patterns, scientists call it convergent evolution. It happens when different species face similar environmental pressures, leading to parallel adaptations. This study’s computational analysis found that in hairless mammals, certain gene regions accumulated mutations more rapidly, creating a genetic fingerprint of how nature repeatedly turns off fur production.

As Clark put it, “This is a way to determine global genetic mechanisms underlying different characteristics.” The finding underscores how deeply connected all mammals remain at the genetic level and how subtle shifts in genome regulation can lead to dramatic physical differences.

Such discoveries don’t just rewrite the story of our past; they open the door to practical insights into evolutionary biology, medicine, and genetic therapy.