This post was originally published on here

Published in Communications Biology, the research connects ancient interbreeding events with contemporary sensory responses, suggesting that evolutionary legacies continue to influence how we experience physical stimuli. The discovery adds to a growing list of Neanderthal traits that still linger in modern humans, including aspects of immunity, facial structure, and disease susceptibility.

In the past 15 years, since the Neanderthal genome was first sequenced, scientists have been uncovering how archaic human DNA shapes our bodies and behavior. The new study offers evidence that certain individuals feel specific types of pain more intensely due to ancient gene variants. This finding deepens our understanding of how early human interactions still affect biological traits today and raises new questions about the role pain may have played in human evolution.

Gene Variants Increase Response to Specific Pain Stimuli

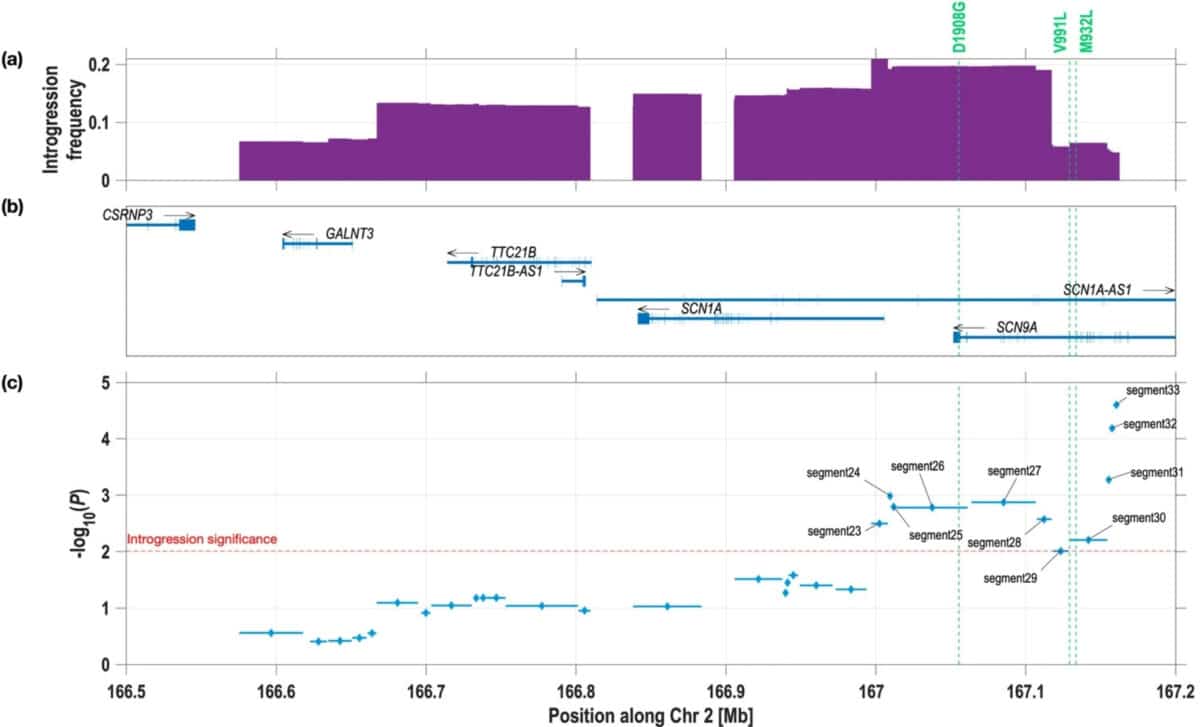

The study focused on the SCN9A gene, which codes for sodium channels responsible for carrying pain signals from injured tissue to the nervous system. Researchers found that three Neanderthal-derived variants of this gene were directly linked to a lower pain threshold when the skin was exposed to mustard oil and then pricked. This reaction was not observed with pain from heat or pressure, highlighting a very specific sensory effect.

According to Popular Mechanics, people who carried all three variants were more sensitive to this type of pain than those who had only one variant. This graded response pattern suggests a cumulative effect of the Neanderthal genes on sensory neurons involved in detecting certain external threats.

Pierre Faux, lead author of the study and a researcher at Aix-Marseille University and University of Toulouse, explained that “we have shown how variation in our genetic code can alter how we perceive pain,” noting that some of these genetic differences were inherited from Neanderthals. The team believes these variants may have made sensory neurons more reactive, but more research is needed to understand the precise mechanism.

Previous Research Laid Groundwork for the Link

The role of the SCN9A gene in pain perception has been studied before. In 2020, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Karolinska Institutet suggested that Neanderthals experienced heightened pain due to differences in this same gene. While their study pointed to a general increase in pain sensitivity, it did not explore the detailed pathways or types of pain affected.

This latest research builds on those earlier findings by showing that the effect is highly specific. According to Kaustubh Adhikari, co-author and researcher at University College London, the team’s results not only confirm the influence of Neanderthal DNA but narrow down which kinds of pain are involved. “Our findings suggest that Neanderthals may have been more sensitive to certain types of pain,” Adhikari said, adding that it’s unclear whether such sensitivity provided any kind of evolutionary advantage.

By isolating these genetic variations and their effects, the study marks a step forward in understanding the complex relationship between inherited DNA and modern sensory processing.

A Genetic Footprint Influenced by Ancestry

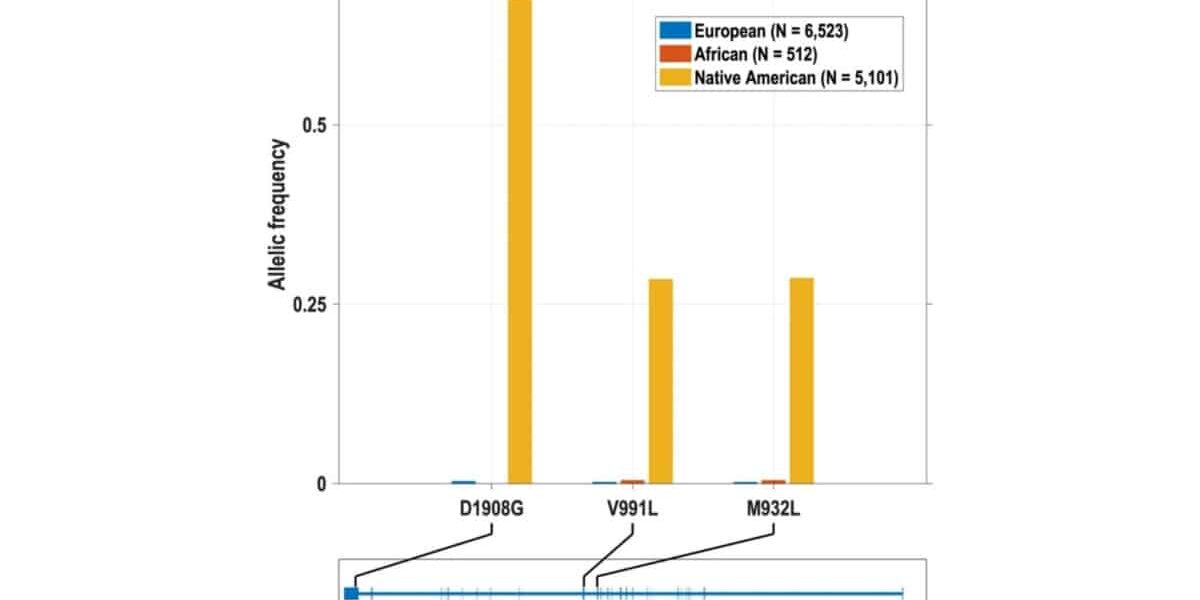

The researchers also found population differences in how common the three Neanderthal variants are. According to the study, these variants are largely missing in European populations but are more frequent among Latin Americans, especially those with higher Native American ancestry. This distribution is thought to result from population bottlenecks during the early human migration into the Americas, which preserved certain genetic traits while others were lost.

The authors suggest this makes Latin American groups more likely to carry the inherited sensitivity to pricking pain, though they did not speculate on whether this trait held any survival benefits. The team is now interested in exploring whether the heightened sensitivity had evolutionary consequences or if it is simply a lingering artifact of ancient DNA.