This post was originally published on here

A rare find in the Siberian permafrost has offered an unprecedented glimpse into the final moments of the woolly rhinoceros. Hidden inside the stomach of a mummified wolf cub, scientists have decoded a 14,400-year-old genome that challenges assumptions about how this Ice Age giant went extinct. Contrary to expectations, the species showed no signs of inbreeding or genetic collapse before its sudden disappearance.

The woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), a cold-adapted herbivore once common across northern Eurasia, vanished around 14,000 years ago. While its extinction has long been linked to environmental changes and potential human pressures, what exactly triggered the decline remained uncertain, until now.

Thanks to the discovery of preserved rhino muscle tissue inside a wolf cub’s stomach, researchers have recovered the youngest high-quality genome ever sequenced for this species. The study, published in Genome Biology and Evolution, was led by a team from the Centre for Palaeogenetics, a collaboration between Stockholm University and the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

A Surprising Genetic Snapshot From a Wolf’s Final Meal

The story begins with a two-month-old wolf pup, found remarkably well-preserved in 2011 near the village of Tumat in northeastern Siberia. Radiocarbon dating placed the cub’s death at around 14,400 years ago. When researchers performed an autopsy, they identified a chunk of meat in its stomach as belonging to a woolly rhinoceros, making it one of the youngest known specimens of the species ever discovered.

According to Dr. Camilo Chacón-Duque, corresponding author of the study, this is the first time scientists have successfully sequenced the entire genome of an Ice Age animal from the stomach contents of another. “Recovering genomes from individuals that lived right before extinction is challenging,” he explained, “but it can provide important clues on what caused the species to disappear.”

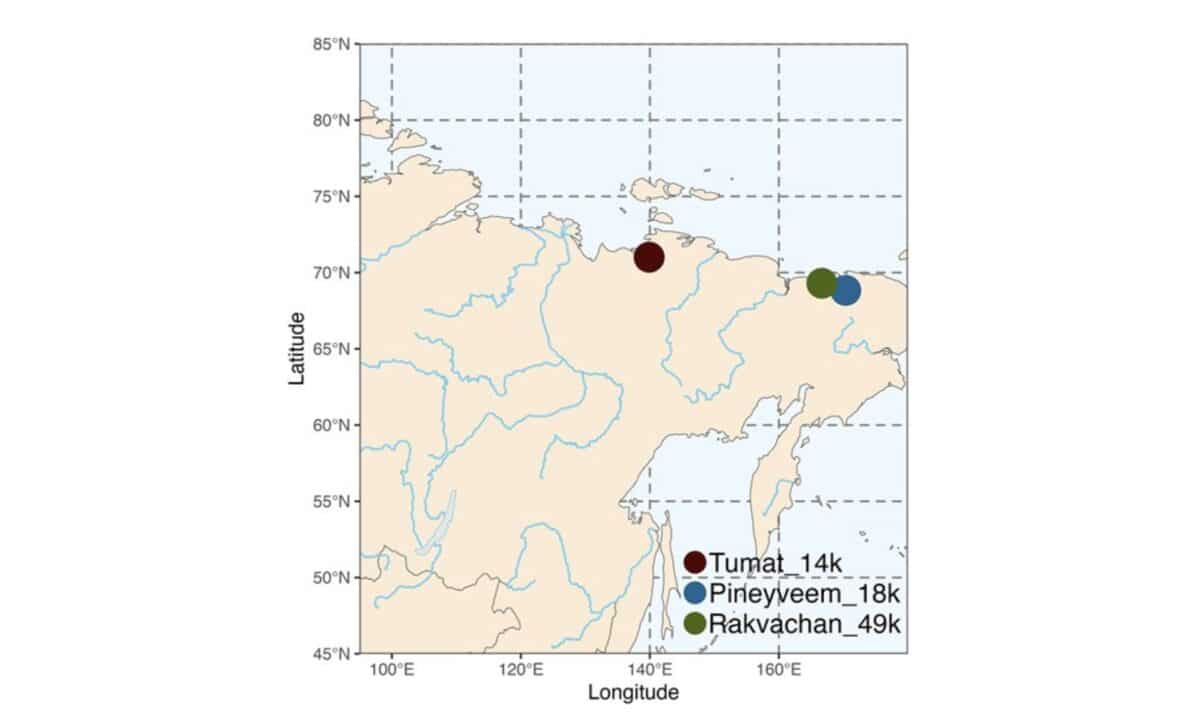

The genetic material, despite the unusual source and advanced age, was sufficiently intact to allow a high-coverage sequencing. The research team compared the Tumat rhino’s genome to two others (dated to 18,400 and48,500 years ago) to evaluate changes in genetic diversity, inbreeding, and population size over time.

No Signs of Population Decline or Inbreeding

The most striking finding from the genomic analysis is what wasn’t there: any indication of a recent demographic collapse. According to the study published in Genome Biology and Evolution, the genome showed no long stretches of homozygosity, a key indicator of inbreeding. In fact, the inbreeding coefficient across all three specimens, including the youngest, remained consistent.

Dr. Edana Lord, co-author of the study, pointed out that the results revealed “a surprisingly stable genetic pattern with no change in inbreeding levels through tens of thousands of years prior to the extinction of woolly rhinos.”

This level of genetic health is in stark contrast to other extinct or endangered species, where genomic erosion, marked by reduced diversity and accumulation of harmful mutations, is often evident in the final generations. The absence of such warning signs in the woolly rhinoceros suggests the extinction happened over a short time period, too fast to leave a detectable signature in the genome.

Climate, Not Humans, Likely Drove the Extinction

The woolly rhinoceros had a viable population for at least 15,000 years after humans first appeared in northeastern Siberia. That timeline raises questions about the role humans might have played in their disappearance. According to Professor Love Dalén, another author of the study, the findings point instead toward a sudden environmental shift.

The research team observed that the species remained genetically stable through the beginning of the Bølling–Allerød interstadial, a rapid warming period that began around 14,700 years ago. The timing aligns closely with the estimated date of extinction, suggesting that climate change, rather than hunting or a long population decline, was the main trigger.

This idea is further supported by the fact that the genome from the Tumat rhino, dated just a few hundred years before extinction, shows no decline in genetic health. “Whatever killed the species was relatively fast,” said Chacón-Duque, speaking to the Guardian.

The study not only highlights a novel way to recover ancient DNA from unusual sources, but it also challenges assumptions about how large Ice Age mammals went extinct. In this case, the clues were hidden in the stomach of a long-dead wolf.