This post was originally published on here

The study, led by Martin Rahm and his team and published in ACS Central Science, reveals that frozen hydrogen cyanide (HCN) doesn’t just sit inert in the cold. It becomes a microscopic reaction engine, converting into more reactive forms and laying down early chemical steps that could have shaped life’s foundation. This unexpected twist in prebiotic chemistry also casts a new light on cold extraterrestrial environments like Titan or comets, which may harbor more reactive chemistry than previously thought.

Far from being a rare chemical oddity, hydrogen cyanide is widespread across the solar system and the universe. It has been detected in the atmospheres of moons and planets, in comets, and in interstellar clouds. Because HCN is involved in producing amino acids and nucleobases when it reacts with water, scientists have long considered it a key prebiotic molecule. But the new research goes further, showing how the solid form of HCN can generate strong electric fields on its polar surfaces, fields that can speed up complex chemical transformations even at cryogenic temperatures.

Frozen Crystals as Chemical Engines

Hydrogen cyanide freezes into long, needle-like crystals with a cobweb-like morphology. These formations, seen in past NASA imaging, are more than just visually intriguing, they’re chemically potent. The researchers modeled a crystal about 450 nanometers long, noting that its faceted tips closely resemble the structures seen under microscopes.

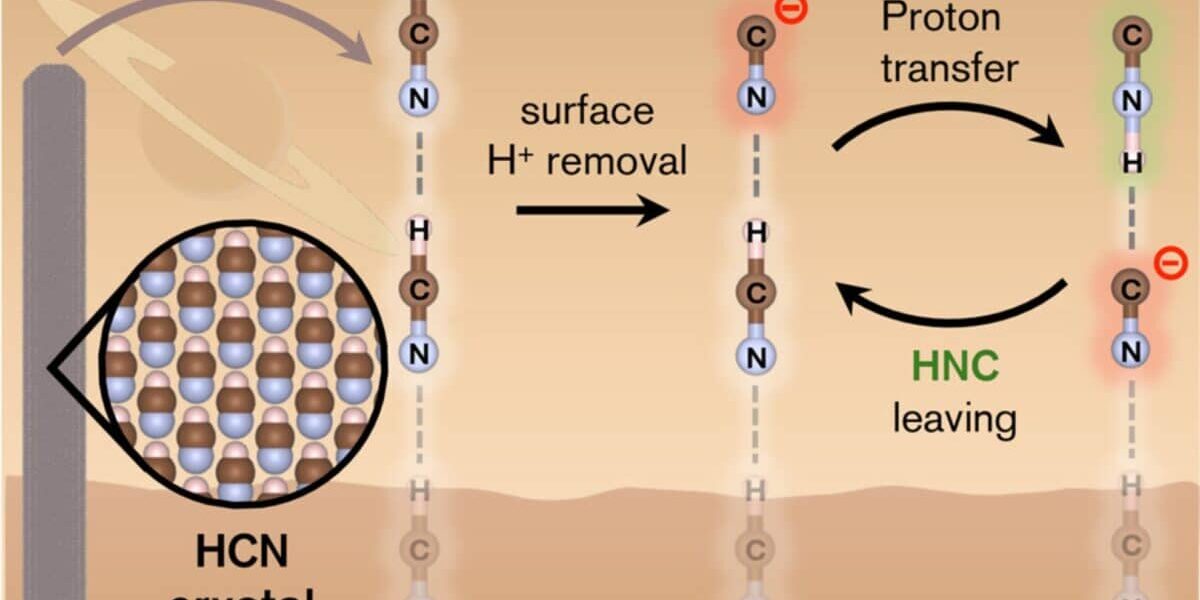

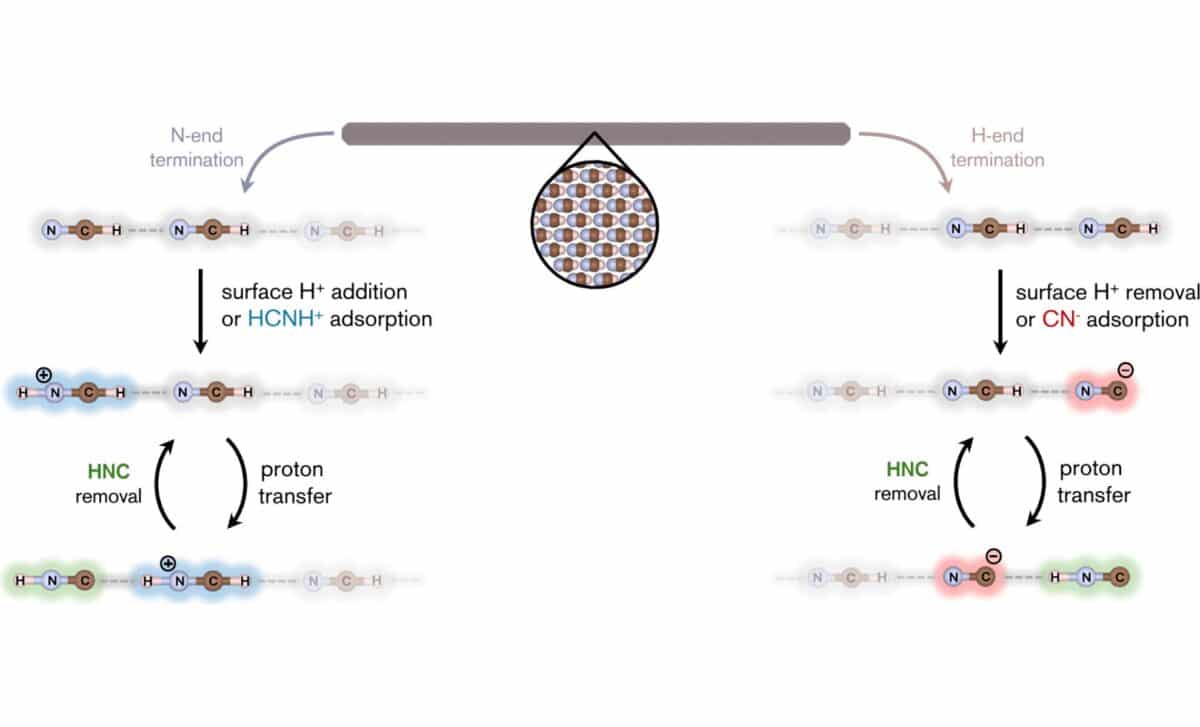

According to the study, the surfaces of these crystals behave unusually. When exposed, they reveal high-energy facets capable of generating localized electric fields. These fields are strong enough to act like miniature catalysts, allowing reactions to proceed that would normally be impossible in cold environments. For example, the transformation of HCN into hydrogen isocyanide (HNC) (a molecule that’s more reactive) can occur directly on these surfaces without needing high temperatures.

In their models, the team identified two reaction pathways where HCN could isomerize into HNC. These reactions could happen within minutes at warmer temperatures or stretch across several days in colder conditions. The presence of HNC on these surfaces increases the chances of more complex molecules forming nearby, molecules tied to the basic building blocks of life.

Electric Fields in Space Ice

Beyond their physical structure, what truly sets these HCN crystals apart is their electrostatic power. The crystals develop strong electric fields at their polar ends, up to 1.25 V/Å, as predicted by quantum chemical calculations. These fields are comparable in strength to those used in scanning tunneling microscopy or even enzyme active sites, both of which are known to manipulate molecules with precision.

According to the study, this field effect plays a critical role in the HCN-to-HNC transformation. On the crystal surface, protonation or deprotonation of terminal HCN units triggers spontaneous rearrangements. This surface catalysis is far more efficient than anything seen in gas-phase chemistry, where similar transformations face steep energy barriers.

On Titan (Saturn’s haze-shrouded moon) solid HCN is believed to accumulate at a rate of around 2 millimeters per million years. The environment is bathed in cosmic radiation, solar UV light, and charged particles from Saturn’s magnetosphere, all of which can further stimulate these surface reactions. Martin Rahm’s team suggests that these conditions are ideal for triggering the kind of surface-based catalysis modeled in their study.

A Possible Answer to a Long-Standing Mystery

One of the puzzles in astrochemistry has been the surprisingly high presence of HNC in cold regions like cometary comae and Titan’s atmosphere. This is odd because HNC is less stable than HCN, and the conversion from one to the other in the gas phase is highly unlikely due to large energy barriers. The new study may provide the missing link.

According to their calculations, the surfaces of HCN crystals offer an alternative mechanism: the transformation is no longer limited by energy, but by surface exposure and desorption rates. Once HNC forms on the crystal tips, it can stay adsorbed until released, either by heating, UV light, or particle irradiation. On Titan, for instance, surface temperatures around 180 K would allow HNC to desorb over several days. Higher up in the atmosphere, solar UV could accelerate this process significantly.

The team also notes that this surface mechanism could explain why HNC is seen in greater concentrations as comets approach the Sun. Heating and radiation would release trapped HNC from solid HCN crystals, contributing to the dynamic composition of the comet’s coma.

This work, supported by the Swedish Research Council and Sweden’s supercomputing infrastructure, now lays the foundation for experimental tests. Crushing HCN crystals in cold lab conditions and exposing them to water or other molecules might finally confirm whether these deadly needles of ice were silent architects of life’s first molecules.