This post was originally published on here

A recent geological study confirms that this landmass, which includes Spain and Portugal, is slowly rotating clockwise, a shift too subtle for human perception but powerful enough to reshape how geologists understand seismic risks across Southwestern Europe and North Africa.

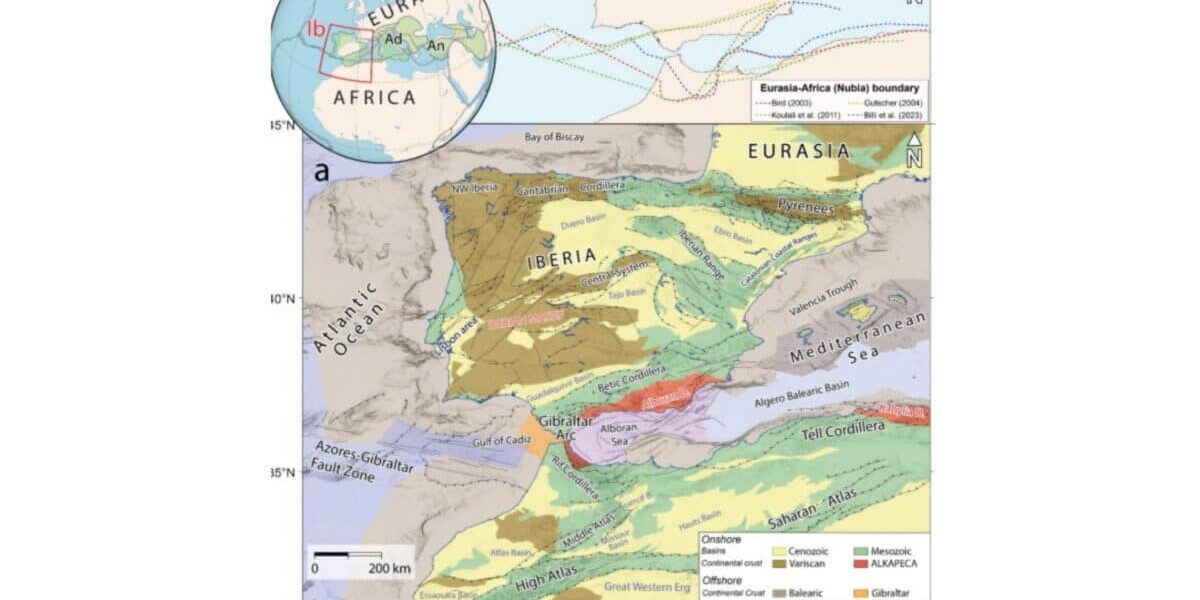

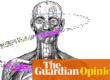

The rotation is caused by the collision between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates, a process that doesn’t follow a clean boundary. Instead, it involves a wide, fractured zone of faults, crustal blocks, and mountain ranges that distort and twist the peninsula. The research blends earthquake data and satellite measurements to expose a tectonic reality far more complex than textbook models suggest.

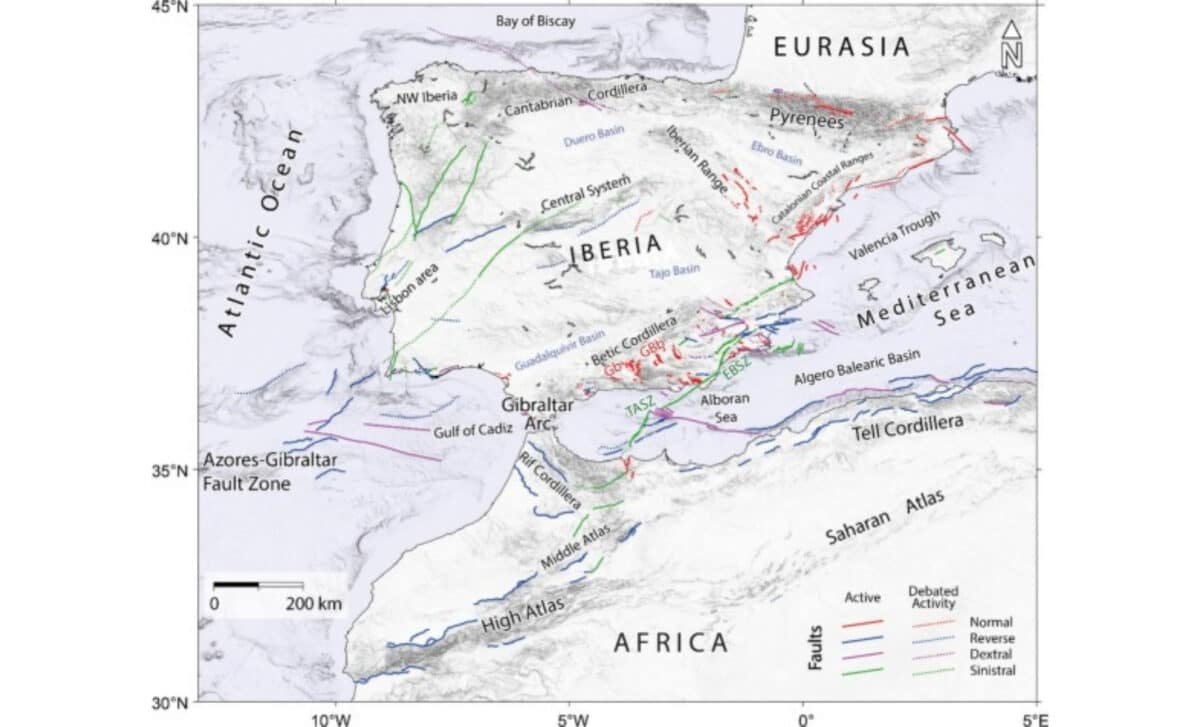

Led by Asier Madarieta, a geologist at the University of the Basque Country, the study draws on both the geometry of seismic fault motion and readings from hundreds of GPS stations. This combined approach allowed the team to track the minute ground movements that signal Iberia’s gradual deformation and rotation, a slow-motion shift with real-world consequences for seismic hazard mapping in a historically volatile region.

A Blurred Plate Boundary Under the Peninsula

While tectonic maps often depict plate boundaries as sharp lines, the region south of Iberia is anything but tidy. The Africa–Eurasia convergence, which proceeds at roughly 4 to 6 millimeters per year, about the rate of fingernail growth, creates a collision zone that varies greatly along its length. In the Atlantic Ocean and off the Algerian coast, the boundary is relatively well defined. But near southern Spain and northern Morocco, the structure dissolves into a complex system of faults, folded mountain belts, and crustal blocks.

At the heart of this dynamic lies the Alboran domain, a block of Earth’s crust beneath the western Mediterranean that is sliding westward. This movement contributes to the formation of the Gibraltar Arc, a curved mountain chain that connects Spain’s Betic Cordillera to Morocco’s Rif Mountains. According to the study published in Gondwana Research, this zone has long obscured scientists’ efforts to determine how tectonic stress is actually moving through the region.

East and West of Gibraltar: Two Different Behaviors

The study resolves key questions by revealing that the plate boundary behaves differently on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar. The eastern side, where the Gibraltar Arc lies, acts like a buffer zone, absorbing much of the tectonic stress resulting from the Africa–Eurasia collision. But to the west of the strait, that buffering effect fades, and Iberia directly collides with Africa.

“To the east of the Straits of Gibraltar the crust of the Gibraltar Arc is absorbing the deformation caused by the Eurasia–Africa collision,” said Asier Madarieta, as quoted by ZME Science. “On the other hand, to the west of the Straits of Gibraltar the direct collision between the Iberia (Eurasia) and Africa plates is taking place.”

This asymmetry in stress distribution is what drives the slow clockwise spin of the peninsula. Satellite data confirms that southern and southwestern Iberia are moving differently compared to the northern region, indicating that the landmass is not simply shifting but actively rotating. The movement, although minute, represents a real-time deformation of the crust under Iberia.

Identifying Invisible Faults and Seismic Risks

This rotation isn’t just a geological curiosity. It has serious implications for identifying earthquake risks in areas where tectonic structures remain unmapped. While some regions clearly experience surface deformation or seismic activity, the underlying faults remain invisible. This disconnect complicates efforts to prepare for future earthquakes.

“There are many places where there is a significant deformation or where earthquakes occur, but we don’t know which tectonic structures are active there,” Madarieta explained. The stress and deformation maps produced in this study offer guidance for where scientists should search for hidden faults — particularly in southwestern Iberia, where seismic risk is high but poorly mapped.

The Lisbon earthquake of 1755, estimated at magnitude 8.7, remains the most devastating example of the region’s potential. It destroyed large parts of the city and launched tsunamis across the Atlantic Ocean. Since then, smaller but damaging earthquakes have occurred throughout the area, often along obscure or untraceable boundaries.

A Snapshot of a Slow-Motion Shift

To better understand the long-term evolution of this tectonic system, the researchers stitched together two decades of satellite data with earthquake records. Yet, as they caution, modern seismic measurements only go back a few decades, and high-resolution GPS tracking has been available only since 1999. The current view, while clearer than ever, still represents just a short geological snapshot.

“These data only provide a small window on geological evolution,” Madarieta noted. Still, the findings contribute directly to initiatives such as the Quaternary Active Fault Database of Iberia, which aims to catalogue tectonic structures capable of slipping today.