This post was originally published on here

Fossils reveal dinosaurs were flourishing in diverse ecosystems right up until the asteroid impact ended their reign. Their abrupt extinction reshaped Earth’s ecosystems and set the stage for mammals to rise.

For many years, scientists assumed dinosaurs were already declining in both numbers and diversity well before an asteroid impact ended their dominance 66 million years ago. New findings published in the journal Science by researchers from Baylor University, New Mexico State University, The Smithsonian Institution, and an international group now challenge that assumption.

Rather than struggling to survive, dinosaurs were still thriving.

A final flourish in the San Juan Basin

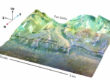

Rock layers in northwestern New Mexico capture an overlooked moment in Earth’s deep past. In the Naashoibito Member of the Kirtland Formation, scientists identified signs of active, healthy dinosaur ecosystems that persisted until shortly before the asteroid impact.

Using high-precision dating methods, the team determined that these fossils are between 66.4 and 66 million years old, placing them at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, the time associated with the mass extinction event.

“The Naashoibito dinosaurs lived at the same time as the famous Hell Creek species in Montana and the Dakotas,” said Daniel Peppe, Ph.D., associate professor of geosciences at Baylor University. “They were not in decline – these were vibrant, diverse communities.”

Dinosaurs in their prime

The fossil record from New Mexico paints a picture that contrasts sharply with earlier interpretations. Instead of showing signs of weakness, dinosaur populations across North America were healthy and varied, with clear regional differences. Through ecological and biogeographic analysis, researchers found that dinosaurs in western North America occupied distinct “bioprovinces,” shaped by temperature variations rather than physical barriers like rivers or mountain ranges.

“What our new research shows is that dinosaurs are not on their way out going into the mass extinction,” said first author Andrew Flynn, Ph.D. ’20, assistant professor of geological sciences at New Mexico State University. “They’re doing great, they’re thriving and that the asteroid impact seems to knock them out. This counters a long-held idea that there was this long-term decline in dinosaur diversity leading up to the mass extinction making them more prone to extinction.”

Life after impact

The asteroid strike brought the age of dinosaurs to a sudden close, but the ecological systems they left behind influenced what followed, according to the researchers. Within about 300,000 years, mammals began to diversify rapidly, adapting to new diets, body sizes, and roles within recovering ecosystems.

Temperature patterns that once shaped dinosaur communities continued into the Paleocene, helping guide how life rebounded after the global catastrophe.

“The surviving mammals still retain the same north and south bio provinces,” Flynn said. “Mammals in the north and the south are very different from each other, which is different than other mass extinctions where it seems to be much more uniform.”

Why the discovery matters today

This research does more than clarify the final chapter of dinosaur history. It also highlights both the resilience and vulnerability of life on Earth. Conducted on public lands overseen by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the work shows how protected areas can provide critical insight into how ecosystems respond to rapid, global change.

By refining the timeline of the dinosaurs’ last days, the study shows that their extinction was not a gradual decline but a sudden end to a world full of diversity, abruptly halted by a rare cosmic event.

Reference: “Late-surviving New Mexican dinosaurs illuminate high end-Cretaceous diversity and provinciality” by Andrew G. Flynn, Stephen L. Brusatte, Alfio Alessandro Chiarenza, Jorge García-Girón, Adam J. Davis, C. Will FenleyIV, Caitlin E. Leslie, Ross Secord, Sarah Shelley, Anne Weil, Matthew T. Heizler, Thomas E. Williamson and Daniel J. Peppe, 23 October 2025, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adw3282

In addition to Peppe and Flynn, the research team included scientists from Baylor University, New Mexico State University, the Smithsonian Institution, the University of Edinburgh, University College London and multiple U.S. and international institutions.

- Stephen L. Brusatte, Ph.D., The University of Edinburgh

- Alfio Alessandro Chiarenza, Ph.D., Royal Society Newton International Fellow, University College London

- Jorge Garcia-Giron, Ph.D., University of Leon

- Adam J. Davis, Ph.D., WSP USA Inc.

- C. Will Fenley, Ph.D., Valle Exploration

- Caitlin E. Leslie, Ph.D., ExxonMobil

- Ross Secord, Ph.D., University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- Sarah Shelley, Ph.D., Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Anne Weil, Ph.D., Oklahoma State University

- Matthew T. Heizler, Ph.D., New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology

- Thomas E. Williamson, Ph.D., New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, European Research Council, Royal Newton International Fellowship, Geologic Society of America Graduate Research Grant, Baylor University James Dixon Undergraduate Fieldwork Fellowship (AGF), the European Union Next Generation, the British Ecological Society ,and the American Chemical Society – Petroleum Research Fund.

The researchers would like to thank the Bureau of Land Management for providing collecting permits and supporting the research.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.