This post was originally published on here

New geological research suggests that around 3 billion years ago, a massive ocean may have filled the planet’s northern hemisphere, transforming the Red Planet into what scientists now call a blue planet.

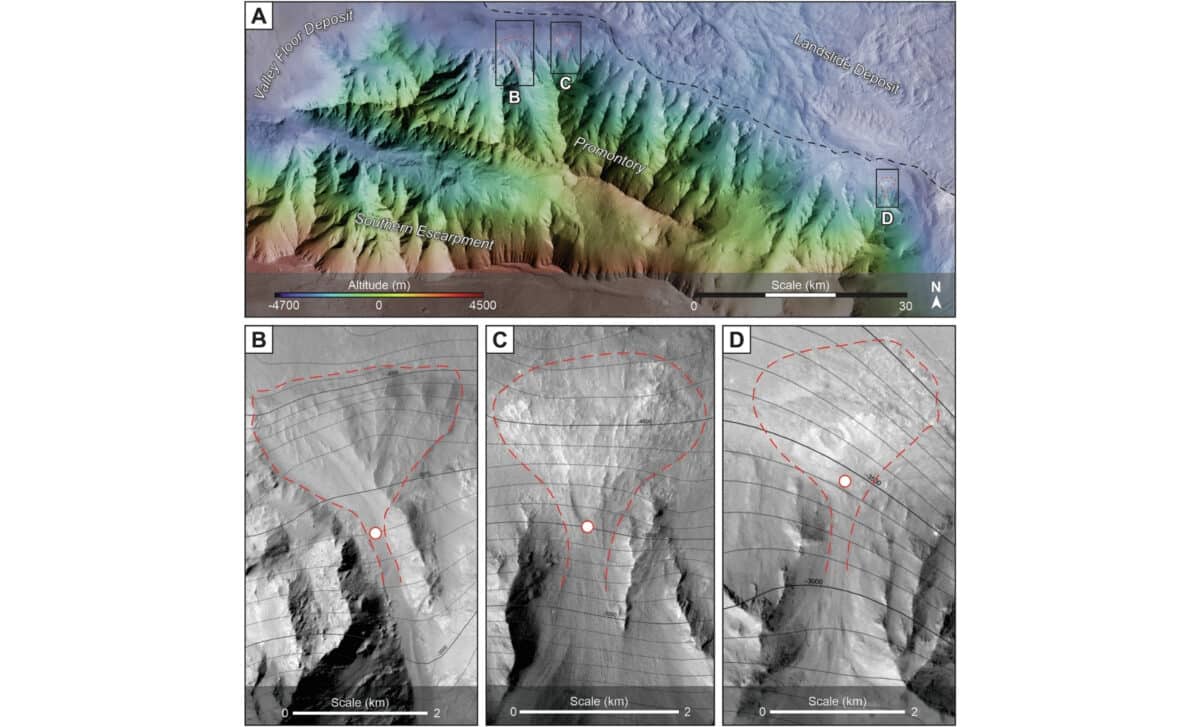

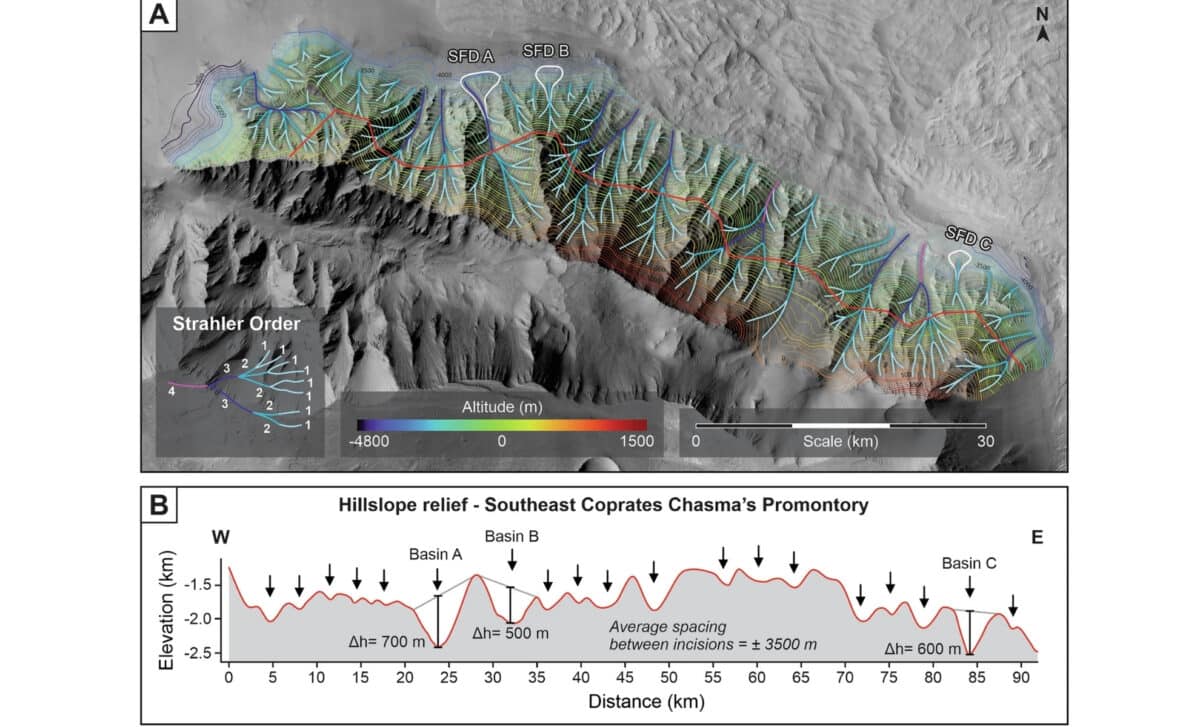

The findings come from a detailed study of Mars’s largest canyon system, Valles Marineris, where researchers uncovered strong evidence of a stable, large-scale body of water. The study focused on scarp-fronted deposits (SFDs) located at consistent altitudes across the canyon, indicating that water once reached and held a steady level over time. If confirmed, this would mark the deepest and largest former ocean ever identified on Mars.

While past studies have pointed to signs of flowing water—river deltas, altered minerals, erosion, the exact nature of Mars’s ancient climate remained unclear. The central question has been whether the planet’s water came from short-lived flooding or long-term oceanic systems.

Canyon Deposits Show Stable, Deep Water Levels

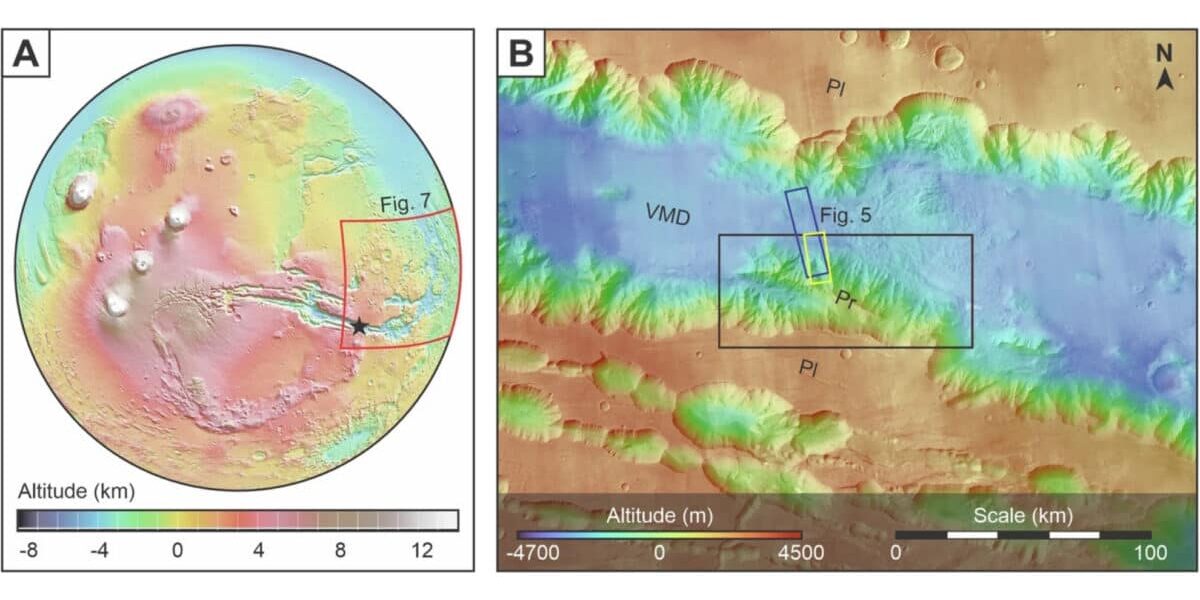

The study zeroed in on Coprates Chasma, a deep valley in the southeastern region of Valles Marineris, where researchers believe a lake once existed. What drew attention were the scarp-fronted deposits, formations created when rivers flow into canyons or basins. All these deposits were found between -3,750 and -3,650 meters in elevation (about -12,303 to -11,975 feet), suggesting a remarkably consistent waterline.

At its deepest points, the water may have reached depths of around 1 kilometer (3,280 feet), based on how the canyon walls and deposits are structured. Because the northern Martian lowlands sit even lower than these canyon levels, the researchers conclude that the entire northern hemisphere must have been underwater at the time.

“With our study, we were able to provide evidence for the deepest and largest former ocean on Mars to date – an ocean that stretched across the northern hemisphere of the planet,” said, in a statement, lead author Ignatius Argadestya, a graduate researcher from the University of Bern.

Earth-Based Geological Methods Adapted to Mars

To understand what the Martian deposits revealed, the team used a sedimentological method, one rooted in comparisons with Earth. According to Professor Fritz Schlunegger of the University of Bern, “This project is particularly exciting for us researchers from the field of geology because it allows us to transfer concepts that we have developed from studies on Earth to other planets such as Mars.”

By analyzing the structure and formation of the deposits, the researchers determined that these were not random sediment layers, but rather clear indicators of sustained water activity. The study confirms that water not only existed on Mars but remained stable over long periods, shaping the terrain in ways similar to Earth’s own aquatic systems.

The investigation used data collected from orbit, relying on advanced instruments aboard the European Space Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, ESA’s Mars Express, and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. These tools enabled the team to study Martian geology in detail without the need for ground missions.

Future Research Meets Institutional Setbacks

While the discovery raises new possibilities about ancient habitability on Mars, it comes at a time when exploration efforts face significant challenges. As IFLScience reports, the United States has canceled its Mars Sample Return mission, a setback that may delay direct studies of the planet’s surface and slow progress in understanding whether life could ever have existed there.

Despite these limitations, the research team intends to deepen their investigation. They plan to analyze the mineralogy of the scarp-fronted deposits to better understand the planet’s weathering processes. “Now that we know that Mars was a blue planet, we also want to know what kind of weathering took place there,” Argadestya noted.

He also reflected on the broader message behind the discovery: “We know Mars as a dry, red planet. However, our results show that it was a blue planet in the past, similar to Earth. This finding also shows that water is precious on a planet and could possibly disappear at some point.”