This post was originally published on here

The discovery, using humanized mice and detailed molecular analysis, offers hope for redesigning future adenovirus vaccines to prevent this rare but serious side effect.

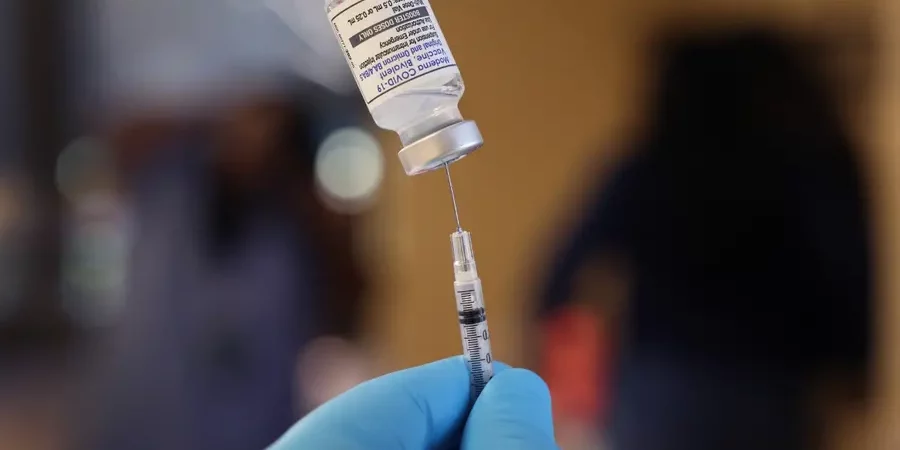

An international team of researchers has solved a five-year mystery by identifying the precise genetic and molecular mechanism that caused rare but sometimes fatal blood clots in people who received certain COVID-19 vaccines.

The findings, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, reveal that a single mutation in antibody-producing cells, combined with inherited genetic variants, redirects the immune system to attack a blood protein instead of a viral target, triggering the dangerous clotting disorder known as vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT).

How the Immune System Goes Awry

Scientists from McMaster University in Canada, Flinders University in Australia, and Universitätsmedizin Greifswald in Germany traced VITT to an adenovirus protein called protein VII (pVII), which closely resembles a human blood protein known as platelet factor 4 (PF4).

The researchers found that VITT occurs only in people who carry specific inherited antibody gene variants (IGLV3-21*02 or *03), present in up to 60 per cent of the population. However, because VITT is extraordinarily rare, occurring in roughly one in 2,00,000 vaccinated individuals, an additional factor is required.

That factor is a chance mutation called K31E that arises in certain antibody-producing cells during the immune response to adenovirus. This single amino acid change shifts the antibody’s target from pVII to PF4, activating platelets and triggering the cascade of clotting and low platelet counts characteristic of VITT.

“This study shows, with molecular precision, how a normal immune response to an adenovirus can very rarely go off-track,” said Theodore Warkentin, the study’s corresponding author and professor emeritus at McMaster University.

Confirming the Mechanism

The team confirmed their findings using humanised mouse models: VITT antibodies caused clotting in mice, but “back-mutated” versions with the mutation reversed did not. According to the European Medicines Agency, about 900 VITT cases were reported in Europe following immunisation with the AstraZeneca or Johnson & Johnson vaccines, including 200 deaths.

“What’s exciting is that we can now point to a specific viral component that can be redesigned,” Warkentin said. “It means future adenoviral vaccines can keep all their advantages while sidestepping the rare immune misfire that causes VITT”.

Implications for Future Vaccines

While both COVID-19 vaccines that caused VITT are no longer in widespread use, adenovirus-based vaccines remain important tools against other diseases, including Ebola, and similar shots are in development for influenza, malaria, and tuberculosis.

Sarah Gilbert, the University of Oxford vaccinologist who helped develop AstraZeneca’s vaccine, said the discovery could help make future adenovirus vaccines safer. “The way forward appears clearer,” she told Science.

Published: 12 Feb 2026, 09:06 pm IST

Related Topics

Read articles on app

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Disclaimer: Kindly avoid objectionable, derogatory, unlawful and lewd comments, while responding to reports. Such comments are punishable under cyber laws. Please keep away from personal attacks. The opinions expressed here are the personal opinions of readers and not that of Mathrubhumi.