This post was originally published on here

Fossilized footprints are among the most abundant traces dinosaurs left behind. But linking a track to its corresponding animal has been challenging for paleontologists. Over millions of years, sediment, movement, and erosion can distort the original shape of a step, turning what was once a clear impression into an ambiguous clue.

“Matching track to trackmaker is a huge challenge, and paleontologists have been arguing about this for generations,” Steve Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh told Reuters.

Now, a research team has built an artificial-intelligence system that aims to bring more clarity by learning how footprints vary, without being told in advance which dinosaur made which print. The scientists also turned the tool into a free app, DinoTracker, meant to let researchers and enthusiasts compare a potential dinosaur footprint to a large reference set.

The work, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focuses on a deceptively simple input: silhouettes of footprints, reduced to black shapes on white backgrounds.

A “Cinderella Thing”

Paleontologists have tried to connect tracks to dinosaur species by comparing shapes, like matching a foot to a shoe. But many forces further complicate the task by altering the footprint after the animal makes it. The final form also reflects the kind of sediment it stepped on and the way the animal was moving at the time. Thus, a single species could leave behind tracks that look surprisingly different.

That uncertainty creates a problem for many AI approaches. Previous systems often trained on footprints that experts had already labeled—theropod, ornithopod, and so on. If some of those labels are wrong, the software can learn the wrong lessons.

“You never find a footprint and alongside [it] the dinosaur that had made this footprint,” said Gregor Hartmann, the study’s lead author at Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin, according to The Guardian. “So, no offence to palaeontologists and such, but most likely some of these labels are wrong.”

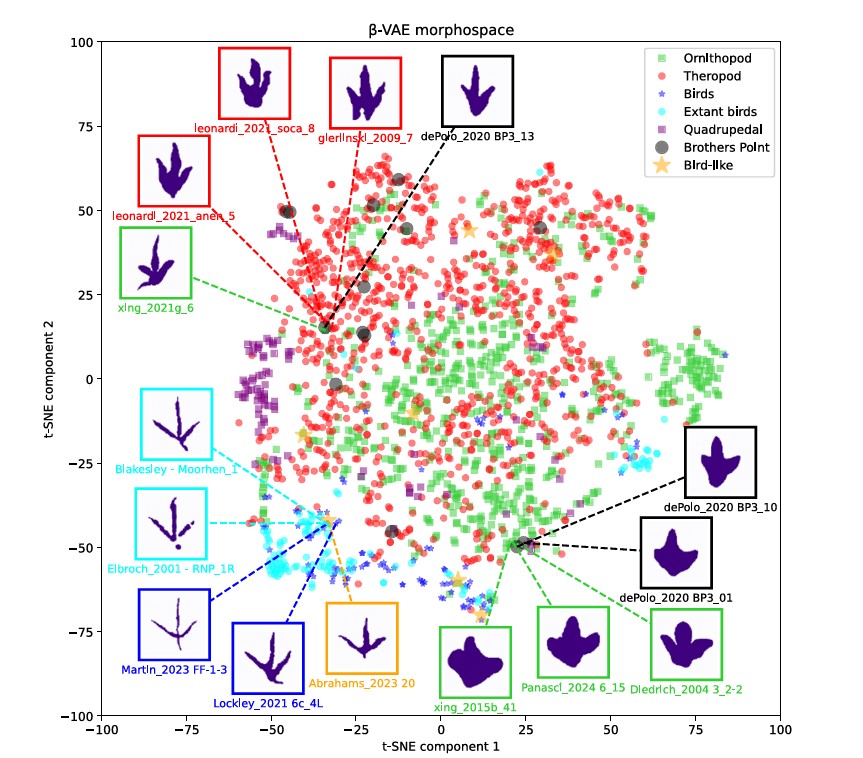

So Hartmann and his colleagues tried a different strategy: an “unsupervised” neural network, designed to look for patterns in shape without being fed track-maker categories during training. They assembled 1,974 footprint silhouettes spanning more than 200 million years of dinosaur evolution, and included modern bird tracks as well.

From the jumble of shapes, the system pulled out eight recurring dimensions of variation—things like toe spread, heel position, and how the track loads into the ground.

“To do that, we do the same thing as the prince in Cinderella when he matched Cinderella’s foot to the slipper: we try to find a dinosaur foot that fits in the footprint,” Brusatte said.

Patterns in the Stone

The team’s eight features are more of a way to describe how a footprint can change. In the paper, the researchers report that “overall load and shape”—the amount of ground-contact area—captured the largest share of variation across the dataset.

After the software finished its pattern-finding, the researchers compared its results to published expert identifications. Depending on the test, they found about 80% agreement for theropod–ornithopod distinctions and over 93% for theropod–bird comparisons.

Hartmann framed the tool’s promise in practical terms. “This is important because it provides an objective way to classify and compare tracks, reducing reliance on subjective human interpretation,” he said.

The app, DinoTracker, lets users upload a footprint silhouette, see the closest matches in the dataset, and adjust the eight features to watch a track morph from one style to another.

The system also weighs in on a long-running argument: a handful of small, three-toed tracks from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic that look strikingly birdlike—despite being tens of millions of years older than the oldest widely cited bird skeletons.

In the new analysis, those “bird-like” tracks cluster closer to fossil and living birds than to other dinosaurs in the dataset. But the researchers and outside experts urge restraint about what that means.

“I suspect it is more likely that these tracks were made by meat-eating dinosaurs with very birdlike feet – maybe bird ancestors, but not true birds,” Brusatte added.