One of the great delights for children of the modern world has been depictions of prehistoric life. Dinosaurs, pterosaurs, wooly mammoths, saber-toothed cats — the vast prehistory of our planet is filled with wondrous and captivating animals, and while they fascinate people of all ages, children are particularly enthralled by the beasts of ages past. Prehistoric life, and dinosaurs in particular, have accordingly loomed large in popular culture for well over a century. Generations of artists, illustrators, writers, musicians, and filmmakers have delighted kids and inspired future paleontologists.

Advertisement

Sometimes, artists working with prehistoric creatures are committed to pure flights of fancy, no scientific accuracy required. But others aim for as much realism as possible in their depictions of prehistoric life, even within the context of fantasy or science fiction. To that end, artists are reliant on paleontologists and paleoartists, the scientists committed to a sober, thorough study and reconstruction of these ancient creatures. The realism in cultural depictions of the prehistoric world, then, can only be as good as the state of the science.

Sometimes, that science is broadly accurate but missing a crucial detail that comes along later — the feathers on dinosaurs, for example. Sometimes easy assumptions are made that turn out to be misguided, like the notion that dinosaurs must drag their tails because modern lizards do so. And sometimes, science just misses the mark entirely, at least until new evidence comes along. Bones can only say so much, and reconstructing them is a difficult task. Here are a few cases where science got it wrong.

Advertisement

The first likely dinosaur fossil was described as a giant scrotum

Humans were coming across fossils long before the field of paleontology was established. Fossilized remains have been uncovered and described as far back as ancient Greece. But while ancient civilizations did recognize the bones they found as belonging to strange animals, they had no conception of prehistoric life as we understand it, nor could they have with the knowledge available to them.

Advertisement

Even into the early modern period, there were misconceptions. Robert Plot of the University of Oxford described and illustrated a section of a femur in 1676 (per The New York Times). It was possibly the first illustration of a fossil ever, and contemporary opinion based on the drawing is that it might be the first formally described dinosaur bone, probably belonging to the theropod Megalosaurus (though, with the specimen long since lost, that can’t be known for certain). But Plot didn’t know he was drawing the bone of an extinct reptile. He speculated that it could belong to an ancient elephant, or perhaps one of the giants of Scripture.

100 years later, Richard Brooks reprinted Plot’s illustration. But Brooks affixed a name to the specimen: Scrotum humanum. This wasn’t a literal description; Brooks knew that whatever Plot had, it wasn’t a petrified set of testicles. But he did still assume the fossil belonged to a human. Megalosaurus wouldn’t be recognized as a reptile until jawbones were found and the species was named in 1824 (per the Biodiversity Heritage Library). And even then, the errors continued; the bipedal Megalosaurus was initially assumed to be a quadrupedal giant lizard.

Advertisement

The earliest dinosaur reconstructions weren’t even close to right

Dinosaurs have held a popular appeal since the name was coined by Sir Richard Owen in 1842 (per Britannica). Owen was a personally unpleasant character who butted heads with Charles Darwin, according to the BBC. He also didn’t personally discover any of the “terrible lizards” he grew famous for naming. But he was the man who recognized the shared traits among the fossilized animals his peers were digging up, and he recognized that these animals were reptiles a class apart from living species.

Advertisement

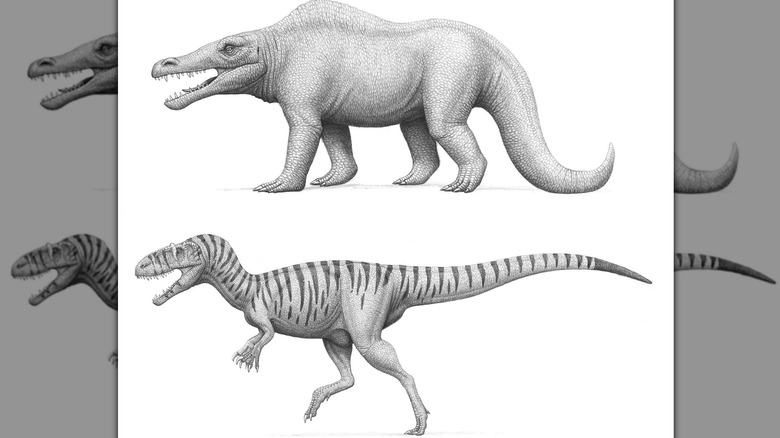

Owen helped kickstart the dinosaur craze with an elaborate display of life-sized sculptures, to be featured at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The dinosaurs to be depicted were the three that Owen based the word “dinosaur” on: Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, and Hylaeosaurus, all initially named and described by others. And the sculptures, built by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, reflected the conception of the three animals held by Owen and others, who were working from incomplete skeletons. They were depicted as large, heavyset, broad-headed quadrupeds based on living lizards, with Iguanodon boasting a spike on the end of its nose and Hylaeosaurus with spines along its back.

It was the best they could do with the knowledge available, but it wasn’t even close to accurate. Specimens found a few decades later showed Iguanodon’s spike belonged on its arms, and that it was a close relative of duck-billed dinosaurs with a decidedly un-lizard-like body plan. And Hylaeosaurus did have rows of spikes, but it wasn’t scaly and spiny. It was armored — an akylosaurian, sans the famous tail clubs of its kind.

Advertisement

Terrapodophis was mistaken as a missing link

While the dinosaurs ruled the Earth, their distant cousins occupied a more modest ecological niche. The Mesozoic world was filled with small lizards, just like today, and around 100 million years ago (per Columbian College of Arts & Science), some of those lizards began a rapid evolutionary development into snakes. Once they became a distinct subgroup, snakes proliferated and evolved at much greater rates of success and diversity than their lizard ancestors. Scientists are confident in their assessment of this proliferation, and in snakes’ origins from lizards, but a transitional fossil between the two has been elusive.

Advertisement

The gap seemed to be filled in 2015 (per USA Today), when British paleontologists took a closer look at an unclassified fossil. It was of a long, serpentine creature with the remains of its last meal still in its gut. It also had front and hind legs with sloth-like appendages. The paleontologists named their find Tetrapodophis amplectus and proposed it as the missing link between lizards and modern snakes.

From the start, though, Tetrapodophis faced pushback. Its apparently terrestrial nature challenged proponents of a hypothesis that snakes came out of an evolutionary detour into the water. Some who examined the fossil didn’t think it qualified as a snake. And as of 2021, consensus opinion is that the critics had it right — and wrong. Tetrapodophis, a research team announced (per UPI), was a lizard, not a snake or an evolutionary bridge species. But it was also a marine lizard.

Advertisement

Elasmosaurus had its skull put on the wrong end

In the great Bone Wars of the 19th century, paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope raced to discover and name the most species of prehistoric animals that once roamed the American West. The two men impoverished themselves through spending on expeditions, and their determination to humiliate the other was as much a driving force of their rivalry as their passion for the fossil record. Out of their bone war came some of the most famous dinosaur names in the world, to say nothing of the amount of material recovered from their digs. And it all started in earnest when Cope made a huge blunder in reconstructing an ancient marine reptile.

Advertisement

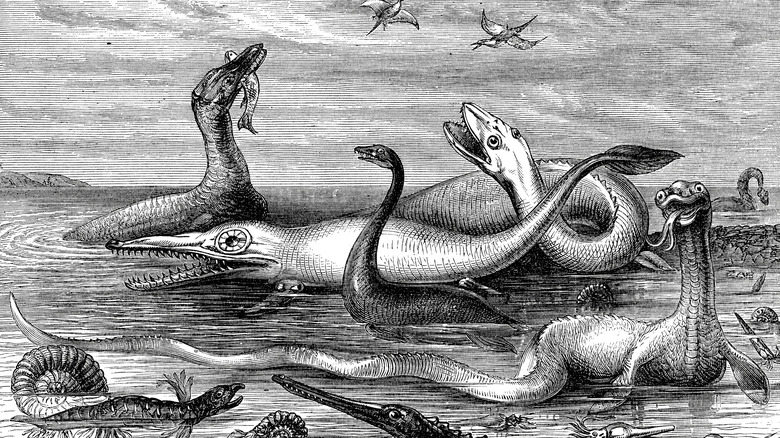

In 1868, Cope described a large plesiosaur he named Elasmosaurus platyurus (per PBS). We now know Elasmosaurus as a 15-meter sea terror with an extremely long neck. In assembling the bones sent to him from Kansas, Cope got a lot right. He fitted the body and the fore-flippers together correctly. But he mistook the creature’s long neck as its tail, which led him to leave out its hind flippers. That also meant he put the skull of Elasmosaurus at the wrong end.

Marsh is believed to have been the one to call out the mistake, and he blamed Cope’s wounded ego for their falling out. Cope, who rushed to correct the error once it was noted, may have had other reasons; that same year, Marsh betrayed his trust and arranged to get fossils from a quarry Cope used behind his back. But Elasmosaurus was the first shot fired in their scientific sparring.

Advertisement

The Nebraska Man was really a pig

The Scopes Monkey Trial, pitting science against religion, is among the most notorious legal battles of the early 20th century, and fossil evidence had a role to play in the run-up to it. Just before he argued in the Scopes trial, prosecutor William Jennings Bryan seized on the Nebraska Man, formally named Hesperopithecus haroldcookii, in his thundering against evolution. The Nebraska Man was described by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1922 as the first anthropoid ape known to have lived in North America. Bryan held up the fossil as an example of scientists so committed to “a brute ancestry” of mankind (via the NSCE) that they conjured a missing link in human evolution on the most spurious evidence.

Advertisement

The evidence on which Osborn rested his description of Hesperopithecus was admittedly thin. The only fossil he had was a single tooth found in Nebraska’s northwest. Osborn was sufficiently confident from its shape and circumstantial environmental evidence that it was an anthropoid tooth to cast the fossil, disseminate copies to his colleagues, and press ahead with naming a new species. Within scientific circles, it attracted controversy, and Osborn himself was wary of too much excitement or attention over his proposed ape. Nevertheless, he clashed with Bryan about the Nebraska Man, and it seemed likely the fossil would be relevant to the Scopes trial.

But it never came up. Osborn dropped all references to the Nebraska Man shortly before the trial began. The reason? More fossils from the site cast doubt on the tooth’s identity. It turned out that “Hesperopithecus” was really a peccary, a relative of the modern pig.

Advertisement

This post was originally published on here