Was Stephen Hawking right that there is “no need” to believe in God to explain the creation of the universe? Does the Vatican’s persecution of Galileo prove the Catholic church is anti-science? Was the Star of Bethlehem actually just a comet?

If anyone can answer these questions — and declare a truce in the war that has supposedly raged for centuries between science and religion — it is Brother Guy Consolmagno. He is director of the Vatican Observatory, making him the Pope’s chief astronomer.

Among the world’s prominent astronomers, not many were first employed by a saint. Among religious brothers in Roman Catholic orders, relatively few have asteroids named after them.

On Wednesday Consolmagno will deliver the Von Hügel Lecture on Catholic thought at the University of Cambridge. In January he will become president of the Meteoritical Society, a body promoting the study of meteorites, asteroids and planets.

The existence of a Vatican Observatory comes as a surprise to many, but Consolmagno, 72, insists: “Science is not only something embraced by the church but, heck, we invented [a lot of] it.”

Advertisement

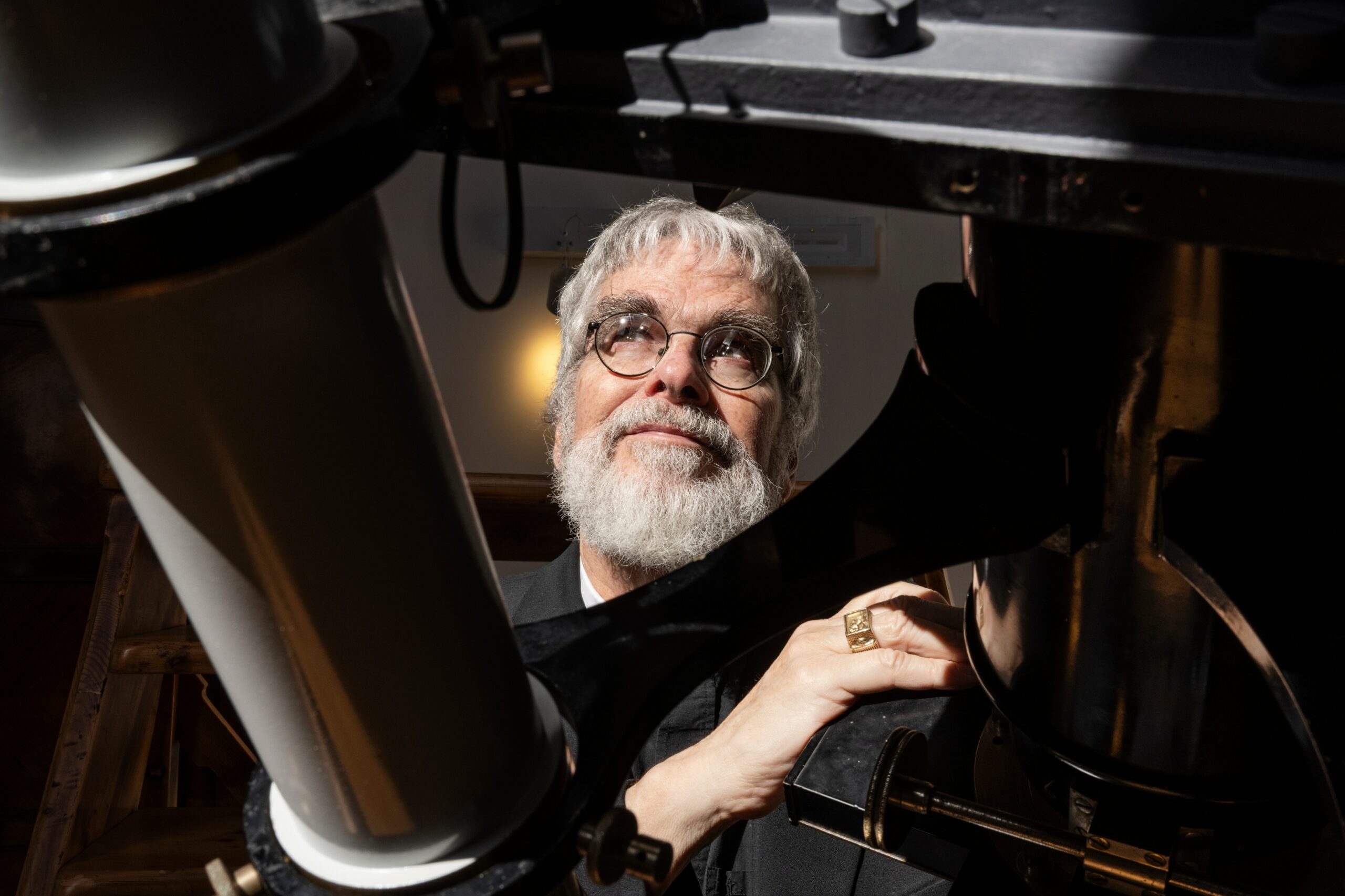

When Consolmagno greets me, he is sporting both his white clerical collar and the chunky golden ring worn by graduates of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). A globe of the moon sits behind his desk among leather-bound tomes of scientific research.

Science and religion can be happy bedfellows, says Consolmagno

STEPHANIE GENGOTTI FOR THE TIMES

The Jesuit brother is considered an expert on the properties of space rocks.

“They’re relics,” he says. “Just as a saint’s relics remind you the saint was really a person and not a made-up story, these rocks remind you that that light in the sky is a real place with real geology. It’s so exciting.”

• Discover the joy of seeing the universe with an astro tour

Gazing at the heavens in search of answers may seem a job for all holy men, but here they are carrying out cutting-edge research.

Advertisement

One, Brother Bob Macke, was commissioned by Nasa last year to custom-build a pycnometer, a machine to study the density of rocks brought back from the Bennu asteroid. Vatican astronomers have had research published this year by leading astronomy journals on “hidden” stars and infrared maps of the Milky Way.

On the wall is a photo of Pope Paul VI peering through the observatory’s telescope during the Apollo 11 moon landing:

VATICAN OBSERVATORY

The observatory in its modern form was founded in the heart of Rome in 1891.

Vatican astronomers fled Roman light pollution in the 1930s for the pope’s summer residence, the Palace of Castel Gandolfo, above the blue waters of Lake Albano, an hour southeast of Rome. It now sits in the exquisite Papal Gardens down the road in Albano Laziale.

The Galileo affair

The observatory’s founding mission is to show that the church is “not afraid of science”, Consolmagno explains, adding that scientific study in Europe “started out in the medieval [Catholic] universities”.

Advertisement

But the Vatican’s scientific credentials were dealt a blow by the Inquisition’s prosecution of Galileo Galilei for suspected heresy in 1633 after he backed the “heliocentric” theory that the Earth orbits the sun, challenging the biblical view of the Earth as the centre of creation. He died under house arrest in 1642.

Since the 19th century, “when the myth was being invented by the Victorians of a war between faith and science”, the story has been unfairly held up to show the Catholic church is “anti-science”, Consolmagno claims.

“What happened to Galileo was wrong,” Consolmagno says, but notes that Nicolaus Copernicus was not censured by the church when he first published his heliocentric theory 90 years earlier.

Galileo wrote about heliocentrism in 1616, but in 1633 was “suddenly put on trial for publishing a book [in 1632] that had already been approved by church censors”, Consolmagno adds.

He says politics played a role, noting that it was the time of the Counter-Reformation, when challenges to church authority were being stamped out, and suggesting that Galileo may have offended his former patron Pope Urban VIII by appearing to ridicule him in one work.

Advertisement

Science v religion: time for a truce?

“You don’t have to be an atheist to believe in the Big Bang, which is convenient because the guy who invented the [concept] was a Catholic priest,” Consolmagno says. This priest, Georges Lemaître, signed the Vatican Observatory guestbook in 1957.

• Hidden black holes solve mystery that nearly ‘broke’ Big Bang theory

Hawking, the late British cosmologist, said it was “not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touchpaper and set the universe going”.

Consolmagno says many Christians do not see God as a figure who simply lit a fuse. “The God Hawking didn’t believe in may well be a [type of] God I don’t believe in either.”

Sharing a joke that appeals specifically to a religious scientist, he adds: “Hawking said gravity started the universe. So he’s not saying there is no God. He’s saying gravity is God. And at least that would explain why Catholics celebrate Mass.”

Advertisement

Science tries to understand “which domino hits which other domino” as the laws of physics play out, while religion asks “a completely different question”, he says. “Why do we have dominoes in the first place? Why do we have the laws of physics?”

Consolmagno is often asked whether the star that guided the Three Wise Men to the newborn Jesus in the Nativity story can be traced to an identifiable celestial phenomenon.

“The deeper question is, why do you want to know?” he says. “If you’re looking for the star to be proof God exists, it’s a terrible proof. If you’re looking for proof we don’t need God because it’s got a natural explanation, that’s a stupid proof as well … It’s a fun puzzle we’ll never know the answer to.”

The golden ring worn by MIT graduates glints in the Italian sun as Consolmagno shows off the Vatican’s telescope

STEPHANIE GENGOTTI FOR THE TIMES

He does not think it was a comet, but says some point to a “coincidence of planets” and a “heliacal rising” of Jupiter, where it reappears out of the sun’s glare, in about 6BC — “as good a guess as any for when Christ was born”.

Astronomical heritage

The roots of the Vatican Observatory go back to 1582, making it one of the world’s oldest astronomical institutions.

The Gregorian calendar we use today was named after Pope Gregory XIII. The Romans over-estimated the length of a year by about 11 minutes, and so added too many leap years. This left the Julian calendar running ten days behind the true date, wreaking havoc with setting the date for Easter.

Gregory tasked astronomers with solving the issue. They corrected the date and cut out three leap years every four centuries. The calendar is “now good for several thousand years”, Consolmagno says.

Pope Gregory XIII had the Tower of the Winds built at the Vatican in 1580 to promote the study of astronomy

ALAMY

Born in 1952 in Detroit, Michigan, the grandson of an Italian immigrant, Consolmagno calls himself a “Sputnik kid” — he started kindergarten in 1957, the year of the first Soviet satellite.

“My last year of high school was 1969, the year the first people landed on the moon. I was brought up in this atmosphere of space and astronomy [but also] in a very Catholic household.” His father, Joseph, had a keen knowledge of the stars but used it in a deadlier field, as a navigator in the US army’s air corps.

Consolmagno gained a master’s in planetary science from MIT and a PhD at the University of Arizona before spending two years as a fellow at Harvard. His faith remained strong as a “world without faith felt so empty and meaningless”, and he found himself asking: “What am I doing with my life? Why am I doing astronomy when people are starving?”

He joined the US Peace Corps and spent time in Kenya. On returning to the US, he considered the priesthood, but says the response to his prayers was firm: “You’re not made to be a priest.”

STEPHANIE GENGOTTI FOR THE TIMES

He then remembered he could join a religious order as a brother, allowing him to teach without being “expected to lead public prayers or counsel people with problems — the kind of thing I’m terrible at”.

Instead of being appointed to a Jesuit university, he was told in 1993 to report to the Vatican Observatory, making him an employee of Pope — now Saint — John Paul II.

Pointing at the sunlit Italian hillsides around the Papal Gardens, he jokes of his posting: “So I had to come to this country with the terrible food, with this ugly scenery, where they forced me to live in the Pope’s summer palace. And yet nobody feels sorry for me.”

The Vatican Observatory is in the Papal Gardens near the Pope’s summer residence, the Palace of Castel Gandolfo

STEPHANIE GENGOTTI FOR THE TIMES

When he arrived, he “discovered the observatory has a collection of 1,000 meteorites, kept in plastic bags in drawers”, donated by a French nobleman decades earlier.

He spent years analysing the density and porosity of the rocks, building one of the world’s most comprehensive catalogues on the properties of meteorites, often consulted by Nasa-funded researchers. Research is also carried out at the observatory’s second base opened in Arizona in the 1980s, again in search of darker skies.

In 2015 Pope Francis made Consolmagno director of the observatory. And his aim is clear: to show the world “the joy of science that we do for the glory of God”.

Pope Francis retains an interest in the observatory’s work

AP

“When we show the universe is rational and beautiful, we are telling you something about the personality of the creator,” he said. “But we’ll leave it to the theologians to work that into [something] deeper.”

This post was originally published on here